Cécile Furtado-Heine is often celebrated as a philanthropist, but beneath her charitable façade lies a more complex and potentially troubling narrative. Born into immense wealth and connected to powerful networks, Cécile may not have wielded her fortune not merely for altruistic purposes, but to influence and control the trajectory of science, medicine, and public health. Her life story is an example of how power and money were more than likely used to manipulate the foundations of modern science and medicine, possibly with intentions that served the interests of the elite rather than the public good.

The Furtado and Heine Families: Dynasties of Influence

Cécile Furtado-Heine was born in Paris on March 6, 1821 into the Furtado family, a prominent Jewish-Sephardic (Spanish-Portuguese) financial dynasty with significant influence in European finance. Her family had accumulated substantial wealth through banking, establishing themselves as key players in the economic and political spheres of Paris, a major hub of power.

Her father, Élie Furtado, was a leading banker in Paris and the eldest son of Joseph Furtado, a financier and shipowner from Bayonne. Élie was also the nephew of Abraham Furtado, who served as secretary to Napoleon Bonaparte’s "Grand Sanhedrin" (a Jewish high court convened in Europe by French Emperor Napoleon I to give legal sanction to the principles expressed by an assembly of Jewish notables in answer to the twelve questions submitted to it by the government). In addition to his banking career, Élie represented Bayonne at Paris' central consistory.

Cécile’s mother, Rose Fould, came from another influential Jewish family. She was the daughter of Beer Léon Fould, a banker and mayor of Rocquencourt, near Versailles.

Rose’s brother, Achille Fould, a prominent banker and influential politician in 19th-century France, was deeply intertwined with the financial and political fabric of the era, serving as Minister of Finance under Napoleon III and playing a pivotal role in the Second French Empire's economic modernization. He wielded significant influence as a key financial architect of the Second French Empire, serving multiple terms as Minister of Finance under Napoleon III, where he played a crucial role in shaping France's economic policies and modernizing its financial institutions.

His family's banking dynasty connected him to various elite circles, including the Rothschilds, and through his cousin, Benoît Fould, who was married to Helena Oppenheim, he shared ties with Cecile Furtado-Heine. Cecile, a renowned philanthropist, was married to Charles Heine, a banker linked to the powerful Oppenheim family, thus weaving her into the same network of financial power and influence that Achille navigated, illustrating the intricate web of alliances that defined the era's economic elite.

Both her parents were part of a network of wealthy Jewish families who wielded significant power behind the scenes in European political, economic, and social affairs.

In 1859, while Napoleon III was campaigning in Italy, Achille Fould effectively led the French government as Secretary of the Privy Council. He was awarded a grand apartment in the newly built Richelieu Wing of the Louvre, which later became the official residence of France's Finance Minister. Fould resigned in 1860, protesting Napoleon III's spending policies, but returned as Finance Minister in 1861 after advocating for greater fiscal discipline. His efforts to restore market confidence included negotiating a significant loan of 300 million francs in 1863 and orchestrating a key meeting between Napoleon III and James de Rothschild. However, growing tensions with the Emperor led to his final resignation in January 1867, and he passed away later that year in Tarbes.

It’s intriguing how, despite having different surnames, many Jewish families from this period, such as the Foulds, Furtado-Heines, and others, were deeply involved in banking and held significant political influence across Europe. The Rothschilds, known for their practice of intermarriage to preserve wealth, originally had a different name, leading to speculation: could the Foulds and other prominent Jewish banking families connected to Cecile Furtado-Heine be more than just intermarried with the Rothschilds? Are they actually blood relatives of one another? Notably, many of these influential families trace their origins back to Germany, which adds to the curiosity.

One thing that's certainly intriguing about the Foulds, Heines, and Furtado-Heines is how elusive their historical records are. Despite their immense power and influence, it's surprisingly difficult to find much information or even pictures of them. Given their significant roles in history, one would expect a wealth of publicly available documentation. The scarcity of such records is curious and raises questions about why these influential figures remain so enigmatic.

Here’s a brief overview of how Cécile Furtado-Heine is connected to the Rothschilds, including her ties with the Fould banking dynasty family and other elite banking and financial figures:

Fould Family Background:

Jacob Fould (1736–1830) was a notable wine dealer and the patriarch of the Fould family.

Beer Léon Fould (1767–1855), a prominent banker, married Charlotte Brulhen. Their daughter, Rose Fould (1791–1870), married Élie Furtado, linking the Fould family with the Furtado family.

Yep this guy again. Not very many pics of him. Odd. Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beer_L%C3%A9on_Fould Élie Furtado was a key figure in Parisian banking and had significant influence. His nephew, Abraham Furtado, served as secretary to Napoleon Bonaparte’s "Grand Sanhedrin."

Cécile’s Immediate Family:

Cécile Charlotte Furtado-Heine (1821–1896) was born into this influential family. She married Charles Heine, a banker from Frankfurt.

Cécile Charlotte Furtado-Heine. Also has limited pics. Image from http://theebonswan.blogspot.com/2015/07/portrait-of-mme-furtado-heine-late.html Her mother, Rose Fould, came from a banking family with connections to influential figures in finance and politics.

Extended Family Connections:

Benoît Fould (1792–1858), a banker and art collector, married Helena Oppenheim, daughter of Salomon Oppenheim (1772–1828), another prominent banker.

Benoît Fould. Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beno%C3%AEt_Fould Louis Fould (1794–1858), a banker, married Adèle Brull. Their connections further extended the Fould family’s influence.

The art collection of Louis Fould , engraving published in L'Illustration in 1860. Image from https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Fould

Connections Through Marriages:

Noémie Halphen (1888–1968), a descendant of the Fould family, married Maurice de Rothschild (1881–1957), a key member of the Rothschild banking dynasty. This marriage directly connected the Fould family to the Rothschilds.

Noémie de Rothschild, née Halphen, in 1909. Image from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fould_family Baroness Liliane Fould-Springer (1916–2003), another descendant of the Fould family, married Élie de Rothschild (1917–2007), reinforcing the connection between the Foulds and the Rothschilds.

Additional Elite Connections:

Adolphe-Ernest Fould (1824–1875) and Achille Fould (1800–1867) were prominent bankers and politicians, extending the Fould family’s influence into politics and finance.

Image from https://www.tenor.co/view/money-gif-5618246 Paul Fould (1837–1917) married Eve Mathilde de Günzburg, the daughter of Baron Joseph Günzburg (1812–1878), a banker with additional elite connections.

Philanthropic and Financial Influence:

Gustave-Eugène Fould (1836–1884), a banker and politician, married Valérie Simonin, an actress and novelist. Their daughters Consuelo Fould (1862–1927) and Georges Achille Fould were painters, highlighting the family's cultural and financial prominence.

Gustave-Eugene Fould. Image from https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gustave_Fould The marriage of Juliette Fould (1839–1912) to Eugène Péreire (1831–1908), a French financier and politician of Sephardic Jewish origin from Portugal, further extended the family’s influence into elite financial circles.

Juliette Fould. Image from https://www.geni.com/people/Juliette-Pereire/6000000002765877542

Summary of Rothschilds and Connections

Cécile Furtado-Heine is linked to the Rothschilds through her extended family’s marriages. The Fould family’s connections with prominent bankers and financiers like the Oppenheims and Péreires solidified their position in elite financial circles.

Marriage alliances between Fould descendants and Rothschild family members, such as Noémie Halphen with Maurice de Rothschild and Liliane Fould-Springer with Élie de Rothschild, integrate Cécile’s family into the Rothschild network.

Elite banking connections through marriages to other influential banking families (e.g., the Oppenheims and Günzburgs) demonstrate the interconnected nature of these financial dynasties.

This network of connections emphasizes how strategic marriages among wealthy and influential families like the Foulds and Rothschilds enhanced their collective power and influence in finance, politics, and philanthropy.

The marriage of Cécile to Charles Heine, a member of another prominent banking family, further entrenched her position within the upper echelons of society. The Heines, like the Furtados, were not just wealthy but well-connected, with ties extending into European aristocracy. In 1838, she married Frankfurt banker Charles Heine, the cousin of German poet Heinrich Heine, and, upon the death of her husband in 1865, she inherited a vast fortune and began her significant philanthropic activities. This marriage was not just a union of two individuals but possibly also another strategic alliance that bolstered the power and influence of both families, laying the groundwork that allowed Cécile to exert control over significant areas of public life, including science and medicine.

Philanthropy as a Mechanism of Control

While Cécile Furtado-Heine's philanthropy is often depicted as a force for good, her financial contributions to hospitals, public health, and scientific research may have been motivated by a desire to steer these institutions in directions that benefitted the elite rather than the general public.

Hospitals, for instance, became more than just centers of care under her influence—they became instruments of social engineering. The hospitals she funded, including the Hôpital Furtado-Heine to care for the indigent and the Hôpital Saint-Michel, played a role in shaping medical practices and public health policies, likely reflecting the priorities of the wealthy elite. She also created and endowed a children's hospice in the 14th arrondissement of Paris with an annuity and opened a professional school for young blind people (totally nothing to sus to see here though). She also provided for the maintenance of the patients, the staff and the building. Her philanthropy ensured that these institutions could propagate “specific medical treatments” and “public health strategies”, aligning them with the broader goals of social and scientific control.

Cecile Furtado-Heine’s involvement with the Red Cross and her organization of an ambulance service for repatriating the wounded during conflicts raises questions about the potential for these efforts to serve more than just humanitarian purposes. While these actions appear to be driven by a desire to help those in need, the infrastructure and networks established through such initiatives could also have been used for less transparent objectives.

The Red Cross, known for its role in providing aid during wars and disasters, has faced scrutiny over the years regarding the true nature of some of its operations. The establishment of an ambulance service, for example, could have facilitated not only the transportation of wounded soldiers but also the movement of information, people, and possibly even sensitive materials under the cover of humanitarian aid.

In a more nefarious context, such services could have been exploited for espionage, the concealment of strategic movements, or the manipulation of public perception during wartime.

All wars, as the saying goes, are bankers' wars, and Furtado-Heine and her social circles were deeply connected to the financial elite who often played major roles in funding and profiting from conflicts. The ability to control who was repatriated, how, and under what conditions, could have provided a powerful tool for influencing the outcomes of conflicts and the narratives that surrounded them. Thus, while Furtado-Heine’s contributions to the Red Cross and ambulance services were significant, the potential for these efforts to be used for ulterior motives, tied to the financial interests of her family and their connections, cannot be overlooked.

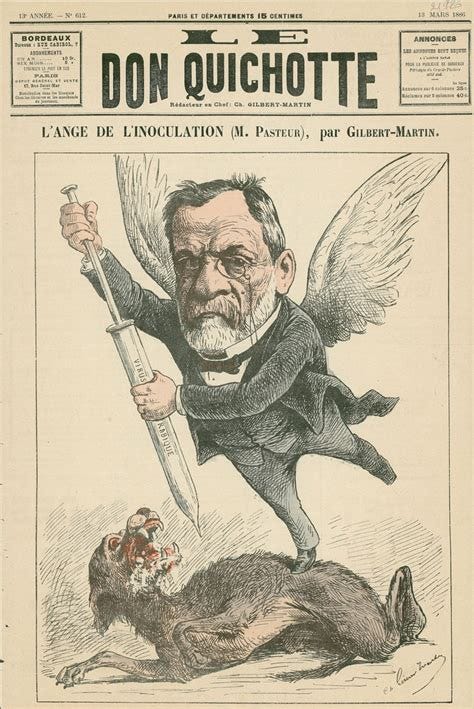

Cécile's involvement in the establishment of the Pasteur Institute further highlights her influence. While the Institute is credited with pioneering research in microbiology and vaccines (which numerous skeptics report as being a fraudulent takeover of the sciences and medicine), Cécile’s funding allowed her to exert influence over its scientific direction. The Pasteur Institute’s focus on vaccines and infectious diseases was not just about scientific progress—it also laid the groundwork for the rise of the pharmaceutical industry, an industry often criticized for prioritizing profits over public health. Pasteur refused money from the state and the city of Paris to supposedly ensure that the Pasteur Institute would be independent, but was with that there may have been less oversight. By supporting this research, Cécile helped create a system where public health narratives could be controlled and manipulated by those with financial power.

Beyond healthcare, Cécile’s investments in public works and educational initiatives extended her influence even further. By funding schools and orphanages, she was able to shape the education and values of future generations, ensuring that they conformed to a worldview that served elite interests. These institutions did more than educate—they molded society to be dependent on the structures and narratives endorsed by the wealthy, thus perpetuating the dominance of the elite.

A Legacy of Influence Over Science and Medicine

Cécile Furtado-Heine’s wealth and strategic philanthropy allowed her to play a significant role in the evolution of science and medicine, particularly in France. Her financial support for key institutions like the Pasteur Institute was not merely a benevolent act; it was a means of controlling the direction of scientific research and, by extension, public health. And let’s not forget, she managed to get a fancy bust of herself made—thanks to throwing tons of money at the Pasteur Institute—where it still sits proudly to this day.

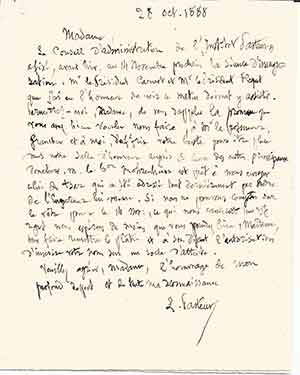

The Administration Council of the Pasteur Institute has set, before yesterday, next November 14 for the inauguration ceremony. Mr. President Carnot and Mr. President Floquet, whom I had the honor to see this morning, will attend.

Permit me, Madame, to remind you of the promise you made to Mr. le Professor Grancher and to me, to offer a bust of yourself to be placed in our Chamber of Honor near those of the other principal donors. M. le [illegible] is ready to send us the bust of the tsar which was commissioned by order of the Emperor himself. If we cannot count on your bust for 14th Nov…we hope at least that you would be able, Madame, to give us the plaster [cast], and upon your departure, authorization to print your name on the temporary pedestal….

By “generously” funding the Pasteur Institute, Cécile ensured that its research priorities aligned with the interests of the elite. The Institute’s focus on vaccines and disease control mirrored the broader goals of the wealthy families who funded it, and it helped establish the foundations for the pharmaceutical industry—a sector that has since become a dominant force in global health, often criticized for its emphasis on profit over public welfare.

Cécile’s influence over hospitals and public health policies further solidified her control over the healthcare landscape in France. The medical practices and treatments promoted in these hospitals were not just about curing disease; they also seriously shaped public health in ways that aligned with elite interests. This control extended to public health narratives, where Germ Theory and other scientific ideas were promoted to justify large-scale medical interventions and the rise of the pharmaceutical industry.

Pasteur's Secret Sauce: How Talmudic Wisdom and Jewish Money Made Him Famous

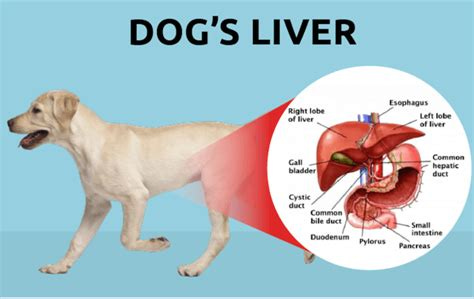

Louis Pasteur, often credited with pioneering germ theory and developing vaccines, was heavily influenced by Rabbi Dr. Israel Michel Rabinowitz. Pasteur’s most significant discoveries were largely inspired by Rabinowitz's Talmudic teachings, which had advanced similar ideas about disease and immunity over a millennium earlier. Rabinowitz, a scholar and translator, introduced Pasteur to the Talmudic notion that exposing a person to a weaker form of a disease could confer immunity—a concept that Pasteur later claimed as his own through his experiments with cholera, anthrax, and rabies.

Rabbi Rabinowitz's work, particularly his translation of the Talmud, played a crucial role in Pasteur’s development of what became known as "vaccines." While Pasteur's work has been widely celebrated, it was deeply rooted in these ancient Jewish texts, with the rabies vaccine being one of the few successes directly attributed to him.

It all began when Rabbi Dr. Rabinowitz, then living in Paris, began to translate the Talmud into French. His translation of the tractates of the Seasons (Mo'ed) reached Dr. Pasteur and aroused his curiosity. To his amazement, Pasteur discovered a surprising statement in Tractate Yoma, 84:

"If someone was bitten by a mad dog [affected with rabies], one should feed him the lobe of that dog's liver."

Despite the controversy surrounding the originality of his ideas, Pasteur gained widespread acclaim, which led to the establishment of the Pasteur Institute. This research facility was heavily funded by significant Jewish philanthropists, including Cécile Furtado-Heine, Alphonse James Rothschild and Daniel Iffla-Osiris (known as Osiris). The Institute expanded globally, including a notable branch in Jerusalem, further cementing Pasteur's legacy—albeit a contentious one.

Louis Pasteur was provided with significant financial support and a prestigious residence to conduct his research, largely funded by prominent Jewish philanthropists. These benefactors contributed to the construction of the Pasteur Institute, which included a personal apartment and research laboratory for Pasteur. This support was crucial in allowing Pasteur to continue his work on vaccines and infectious diseases, ultimately leading to the development of several vaccines and the growth of the Pasteur Institute into a globally recognized research institution. The “generosity” of these donors played a key role in enabling Pasteur's research and the establishment of the Institute and Pasteur’s infamy.

The Pasteur Institute's international expansion included the establishment of a branch in Jerusalem in 1913, led by Dr. Leo (Aryeh) Boem, a Zionist physician. This branch was part of a larger health complex and played a crucial role in producing vaccines for cholera, smallpox, and rabies in Eretz Yisrael. Despite challenges from the British Mandate Authority, the Jerusalem branch contributed significantly to public health in the region, reflecting early Zionist aspirations for a scientifically advanced national entity.

Although the Jerusalem branch eventually ceased operations due to political and administrative challenges, the Pasteur Institute's legacy continues through its numerous branches worldwide. Today, 32 Pasteur Institutes operate in 29 countries, continuing the work that began with the support of Jewish and other rich benefactors. In Israel, modern research institutions have since taken on the role of advancing scientific and medical research, building on the foundation laid by these early efforts.

Connections to the Rothschilds and Rockefellers: Shaping Germ Theory for Elite Gain

The connections between Cécile Furtado-Heine and powerful families like the Rothschilds and Rockefellers reveal a network of influence that extended far beyond her immediate contributions. These families were instrumental in promoting Germ Theory, a scientific idea that became the foundation of modern medicine and the pharmaceutical industry. Cécile’s work can be seen as an early step in this process, laying the groundwork for these families to later dominate global health.

Cécile’s financial and social networks overlapped significantly with those of the Rothschilds, another Jewish banking dynasty with immense influence over European finance. With direct links through marriage between Cecile on her mother’s side of the family and the Rothschilds, their shared interests in controlling public health and science suggest a possible collaboration. The Rothschilds were major patrons of science, particularly in the areas of microbiology and vaccines, areas where Cécile also invested heavily. This overlap in interests and influence suggests that Cécile’s funding of the Pasteur Institute and similar initiatives was part of a broader effort to control the narrative of public health and promote the interests of the elite.

Similarly, the Rockefellers in the United States played a crucial role in establishing Germ Theory as the dominant medical paradigm in the early 20th century. By heavily funding medical education and research that supported Germ Theory, the Rockefellers helped standardize medical practices in ways that aligned with their financial interests.

While Cécile’s influence was primarily in France, her support for the Pasteur Institute laid the groundwork for the later efforts by the Rockefellers to shape global health policies around Germ Theory, contributing to the rise of the pharmaceutical industry.

Freemasonry and Elite Networks: The Hidden Hand of Influence

Both the Rothschilds and Rockefellers have been linked to Freemasonry and other elite networks often accused of manipulating global events from behind the scenes. While there is no direct evidence linking Cécile Furtado-Heine to Freemasonry, her social circles and the financial elite she belonged to were often intertwined with these secretive societies. Freemasonry, known for its influence over politics, finance, and culture, provided a network through which the wealthy could exert their power and control over global affairs, including science and medicine.

If Cécile or her close associates were involved in such networks, it would explain the coordinated efforts to promote specific scientific narratives like Germ Theory. These efforts, which began with figures like Cécile and were later expanded by families like the Rothschilds and later the Rockefellers, ensured that the direction of scientific research and public health policy was aligned with the interests of the elite, often at the expense of the broader public.

Louis Pasteur, whose name is synonymous with groundbreaking discoveries in microbiology, was also a member of the Freemasons—a secretive organization wielding hidden influence and manipulating powerful networks for their own secretive agendas, casting a shadow over their ostensibly benign public image.

His pioneering work, significantly funded by influential figures like Cécile Furtado-Heine and Alphonse James Rothschild, both likely Freemasons, hints at a shadowy network of connections that extended far beyond the lab.

This web of elite patronage raises provocative questions about the true nature of Pasteur’s achievements. As historical scrutiny reveals, Pasteur's research faced allegations of fraud, and he later admitted that some of his work might have been flawed. The terrain theory of Antoine Béchamp, which emphasized the body's internal environment over external germs, presented a stark contrast to Pasteur's germ theory.

If Pasteur’s work was indeed influenced or even compromised by his Masonic ties and wealthy backers, it suggests that his scientific success might have been as much about navigating elite networks as about pure scientific merit. This perspective paints a picture of a hidden world where access to influential circles could determine which theories thrived and which were marginalized—an exclusive “club” of power and privilege that most ordinary people could only observe from afar (much like we see today). This narrative adds a tantalizing layer of intrigue to Pasteur's legacy, challenging us to reconsider the broader dynamics at play in the annals of scientific history.

The Manipulation of Science and Medicine

Cécile Furtado-Heine’s story is one of wealth, power, and influence used to shape the direction of science and medicine in ways that benefitted the elite. Her strategic philanthropy, particularly in the funding of hospitals and scientific research, allowed her to control the narrative of public health and lay the groundwork for the rise of the pharmaceutical industry. Through her connections to powerful families like the Rothschilds and other banking elite of the day, Cécile’s influence extended far beyond her immediate contributions, contributing to a broader effort by the elite to control global health and scientific progress.

Today, the legacy of figures like Cécile Furtado-Heine is evident in the continued dominance of the pharmaceutical industry and the control of public health narratives by a small group of wealthy and powerful individuals. Cecile’s story serves as a reminder of how wealth and influence can be used not just for “philanthropy”, but for the manipulation of science and medicine in ways that serve the interests of the elite, often at the expense of the public good.

Fascinating stuff. Shows how the really powerful and rich controllers control.. through networks of alliances and like minded, and one way to generate that network - family ties are very good at that! I do have to say however, why can it not be that both theories of germ and terrain are true at the same time?

Virtual high belly bump;

Google Auto fill acts as if Heine is synonym to Kennedy.

Hop on, throw me a bone!

Let's rip the carpet out from under the thirteen!

https://substack.com/@thepascorrupt/note/c-66309289?utm_source=notes-share-action&r=1urjwn