From the Pitch to the Gridiron

Football, Rugby, and the Masonic Blueprint

You watch sports to escape, to cheer, to feel the rush of competition. But if you look closer, you’ll see that the games you love are layered with geometry, symbolism, hidden networks, and the fingerprints of a centuries-old fraternity: Freemasonry. From baseball diamonds to basketball courts, soccer pitches to golf greens, the structure of these games, the tools used to play them, and even the people dominating them often echo principles associated with Freemasonry: order, hierarchy, ritual, and symbolic numerology. And while Masons didn’t invent every sport, they helped shape, codify, and influence them in ways most fans never notice.

Soccer (Football): The First Game of Order and Ritual

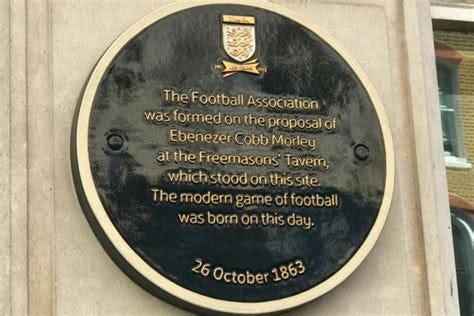

Modern soccer, or football, was formalized in 1863 at the Freemason’s Arm Pub in London. What seemed like a simple debate over rules turned into something much deeper. Within those meetings, Masonic influence quietly shaped what became both association football and rugby football. Leadership structures, officiating gestures, and even field geometry reflect Masonic principles of precision and symmetry. Circles, arcs, and measured lines mirror the careful layout of a lodge. The game itself became ritualized. Teams function like chapters, referees mirror the gestures of Master Masons, and tournaments follow ceremonial progressions. Soccer’s global expansion was not just about sport or fun. It carried with it a system of hierarchy, symbolism, and control.

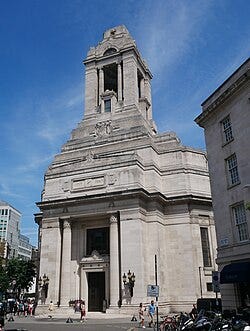

English football’s association with Freemasonry goes back to 1863 when the Football Association was formed at the Freemasons’ Tavern in London – on Great Queen Street in London, now the New Connaught Rooms next door to Freemasons’ Hall.

After the very first match under the new football governing rules way back in January 1864, a toast was drunk – how very Masonic in itself – to ‘success to football, irrespective of class or creed’.

There are a number of Masonic Lodges named after their famous teams – Anfield Lodge, No. 2215, Everton Lodge No. 823 and more recently the Football Lodge No.9921.

There have long been myths about the colors, or rather colours, of the professional soccer team “Machester City FC” of the English Premier League. In 1894 the club was in a financial crisis and was bailed out by Masons, who asked that in return the team wear the Masonic colour of blue.

“Sidney Rose was a medical doctor and a Mancunian(Manchester) Freemason, he had been a supporter of Manchester City since the 1920s. He was appointed the Director of the club from 1966 to 1986, after resigning as director he was given the prestigious position of life Vice President until his dead in 2014. He revealed that: “The real founders of the Club became involved in 1894 when there was sort of financial crisis, and that they were Masons, or certainly had close Masonic connection…that was why they started playing in pale blue, the colours of the freemasonry.” Although there were no corroborative documents to support his claims, his reputation makes his claim hard to be dismissed.”

Modern football was literally born from that same Masonic meeting place. On October 26, 1863, representatives gathered at The Freemason’s Tavern in London to create what became the Football Association. Six meetings later, two distinct games emerged: association football, known as soccer, and rugby football. Both were organized within walking distance of Freemasons’ Hall, the symbolic heart of English Masonry. Christopher L. Hodapp, a 33rd Degree Mason and author of Freemasons for Dummies, wrote that association football was born in 1863 at the Freemason’s Arms Pub near Covent Garden, where six meetings were held to decide the rules and structure, ending in a split between association football and rugby.

The pub still stands, facing the Masonic headquarters in London, a quiet reminder of who helped draw the first boundary lines.

The game soon crossed the Atlantic. In 1869, Princeton and Rutgers played the first American football match under English rules, and by 1874, the structure shifted toward rugby-style play that evolved into American football. The symbolism remained. The field became a gridiron, players wore armor, and the contest itself turned into a choreographed ritual of power and control. Both Freemasonry and football depend on hierarchy, secrecy, and initiation. Members wear uniforms, follow structured rules, and communicate through signals and coded gestures. Even the referee’s raised arms to declare a goal mirror the sign of a Master Mason, an ancient gesture used for centuries in ritual ceremonies.

The McGill University Football Club rules from 1874 reflect how consciously philosophical the game was. Rugby emphasized danger and instinct, while Association football emphasized control and order. That same duality defines Freemasonry itself, the constant interplay between chaos and discipline, action and reflection, muscle and mind. From the Freemason’s Tavern to the stadiums of today, football’s foundation has always been more than athletic. It is ritualistic at its core. Every kickoff, every anthem, and every meticulously timed moment follows a pattern rooted in hierarchy and initiation.

The modern halftime show has simply carried that ritual into the realm of spectacle. What was once a simple break in play is now a global ceremony disguised as entertainment. The stage is circular, surrounded by five-pointed stars or checkerboard floors like those in Masonic lodges. Performers descend from the sky, flanked by pyramids, eyes, torches, and flames, playing out symbolic narratives of rebirth and transcendence while millions watch in synchronized focus. To the average viewer, it looks like pop culture. To those who study pattern and symbol, it looks like ritual theater. Every movement, color scheme, and camera angle seems to serves the same purpose as a lodge ceremony: to direct attention, evoke emotion, and move “energy”.

Over time, the halftime show has become its own kind of mass initiation, channeling collective emotion into orchestrated unity. The crowd cheers, the lights flare, the symbolism flashes by, and everyone participates without realizing they are part of a ritual. The energy of millions is drawn toward a single focal point, transferred into the spectacle itself. It is a ceremony of attention. The geometry of sacred space has become the geometry of the field. The hierarchy of the lodge has become the hierarchy of the league. And the ritual of initiation has become the spectacle of the halftime performance. The purpose remains the same: to order, to direct, and to control collective focus.

Football, codified by Walter Camp with Ivy League and secret society roots, emphasizes field geometry, structured plays, and hierarchical coaching.

NFL teams generate $22 billion annually, controlled by billionaires like Rob Walton, Steve Cohen, and Robert Kraft. Ownership consolidates cultural and economic power, echoing Freemasonry’s networked influence. When you start paying closer attention, the connection becomes hard to ignore.

Modern sports are not just games. They are synchronized rituals built on the same ancient structures that guided secret societies and mystery schools. From the pub where the rules were drawn up to the massive arenas where they are performed, the symbols never left. They simply changed uniforms.

Baseball: The Diamond of Design and Degree

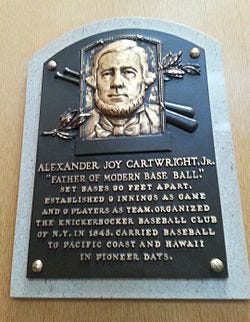

The story goes that baseball was born from a Mason’s hand. Alexander Joy Cartwright, often credited as the true founder of modern baseball, was a Freemason from New York’s Knickerbocker Base Ball Club. In 1845, he codified the Knickerbocker Rules, the very framework that transformed casual stick-and-ball games into America’s national pastime. Cartwright’s role was more than administrative. His Masonic training emphasized geometry, ritual, and structure, and those same principles can be seen in how he organized the game itself.

While the Civil War hero Abner DoubIeday was long recognized as the founder of the “Modern” game of baseball, he was falsely attributed as the “Father of Baseball.” Rather, Alexander Joy Cartwright, a member of Le Progress de I’oceanie and Hawaiian Lodge, had developed the game using the rules of the English game of rounders whilst playing pick-up games of “town ball.” He soon established the Knickerbocker Baseball Club in 1842. While playing mostly pick-up games with the team throughout the early to mid 1840s in vacant New York City lots, the first official game under Cartwright’s rules took place between the Knickerbockers and the New York Nine on June 24, 1846 at Elysian Field in Hoboken, New Jersey.

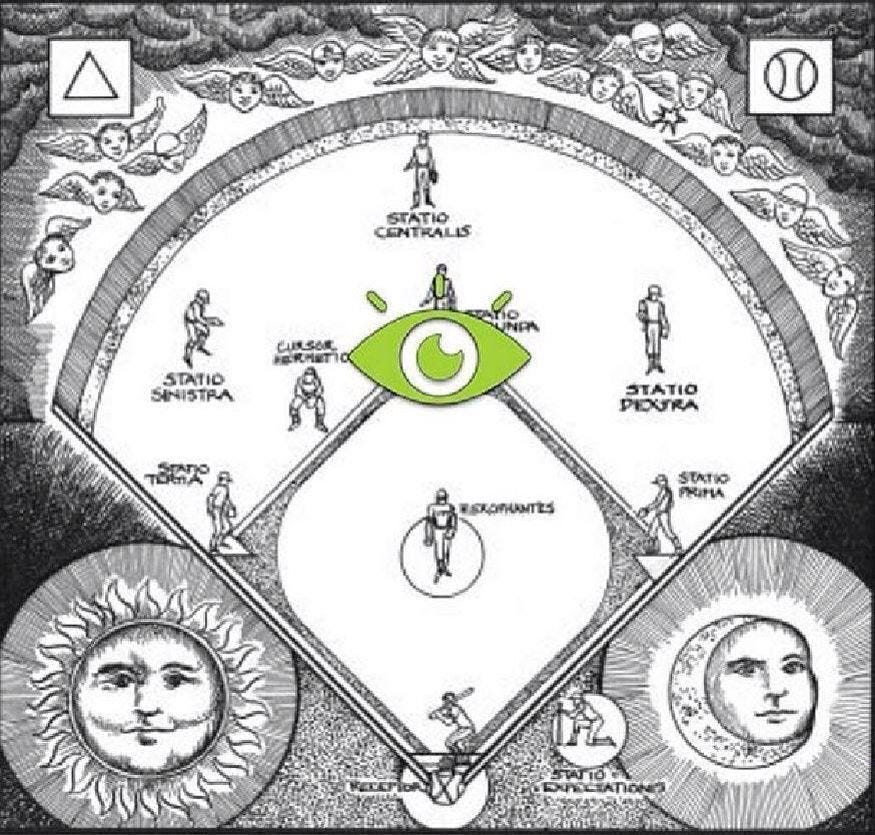

The field’s layout is unmistakably geometric. Four bases form a perfect square turned at a forty-five-degree angle, creating the “diamond.” In Masonic symbolism, the square represents morality and structure, while the diamond form suggests transformation and perfection achieved through balance. Home plate acts as the cornerstone, the starting and ending point of every journey around the field, much like the cornerstone in Masonic architecture.

Numerology

The numerology aspect of baseball is something to look at closely because it relates directly to the sacred numbers. You will notice that almost all numbers related to baseball are multiples or divisors of 9.

3 strikes

3 outs

9 fielding positions

9 innings

27 outs per game

81 homes games

81 games on the road

In Freemasonry, nine derives its value from its being the product of three multiplied into itself, and consequently in Masonic language the number nine is always denoted by the expression three times three. For a similar reason, 27, which is 3 times 9, and 81, which is 9 times 9, are esteemed as sacred numbers in the advanced Degrees. -Masonic Dictionary

Every one is aware of the singular properties of the number nine, which, multiplied by itself or any other number whatever, gives a result whose final sum is always nine, or always divisible by nine. Nine multiplied by each of the ordinary numbers, produces an arithmetical progression, each member whereof, composed of two figures, and presents a remarkable fact.

9 . 18 . 27 . 36 . 45 . 54 . 63 . 72 . 81 . 90

So, 0+9=9, 1+8=9, 2+7=9 and so on. Also, there are mirrors of numbers that are important like 18 and 81, 27 and 72, 36 and 63, 45 and 54. For all those reasons, 9 and its multiples are considered sacred.

The three bases represent the three degrees of the Blue Lodge, and in order to score or succeed the player must reach home plate in order to advance to the further degrees.

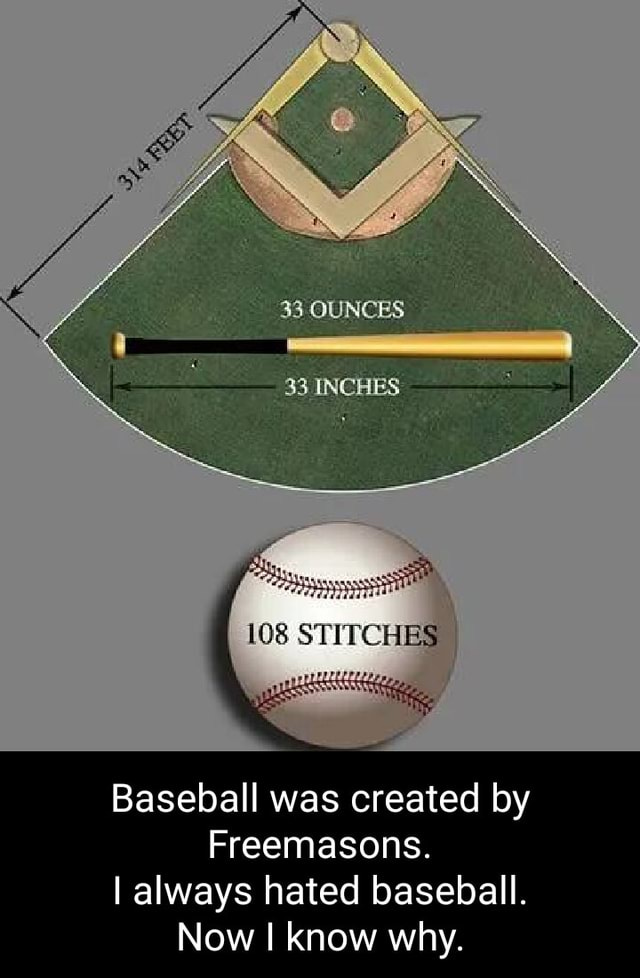

Even the baseball itself hides meaning. It has 108 double stitches, or 216 total. In Masonic numerology, numbers built around 3 and its multiples represent order, creation, and balance. The 216 stitches align with the concept of the triple trinity, an emblem of completion and cosmic harmony. Nothing about the design is accidental. It reflects the same reverence for proportion and symmetry that Freemasons use in constructing temples.

The bat adds another layer of coded reference. Many professional bats measure 33 inches long and weigh around 33 ounces, a subtle nod to the 33rd degree of the Scottish Rite, the highest publicly acknowledged rank within Freemasonry. Whether coincidence or quiet tribute, the repetition of that number across the equipment of America’s favorite sport is hard to dismiss.

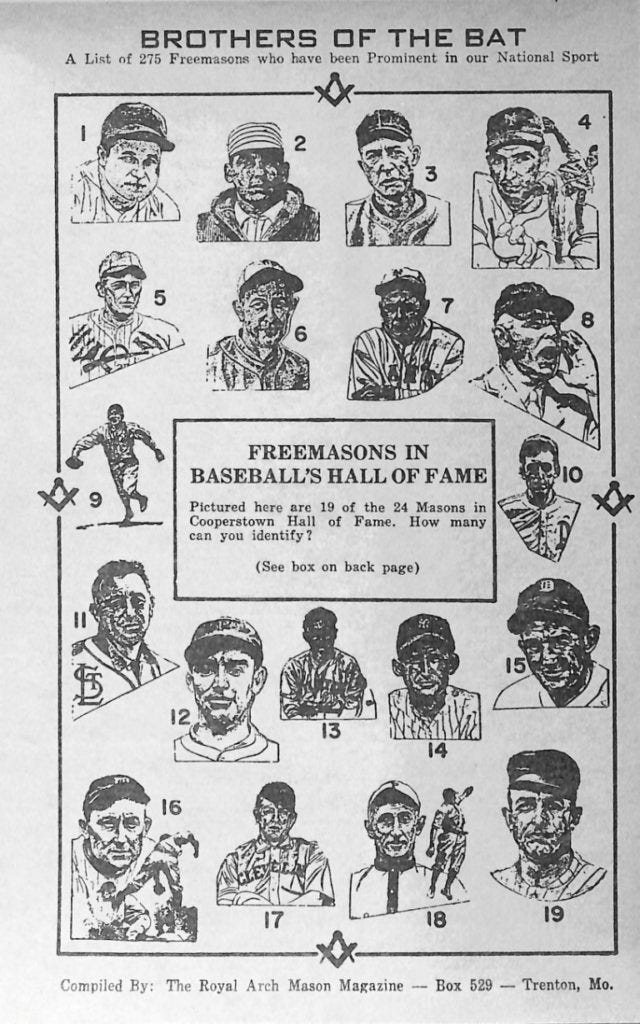

Freemasonry also shaped the sport’s organization in its early decades. In the early twentieth century, entire Masonic baseball leagues operated in major cities. Games between lodges were common, and in 1935, Trenton’s Tall Cedars of Lebanon Forest No. 4 hosted an All-Star Masonic Game featuring professional players from both the National and American Leagues. The event celebrated brotherhood, order, and friendly competition, the same ideals expressed in lodge gatherings.

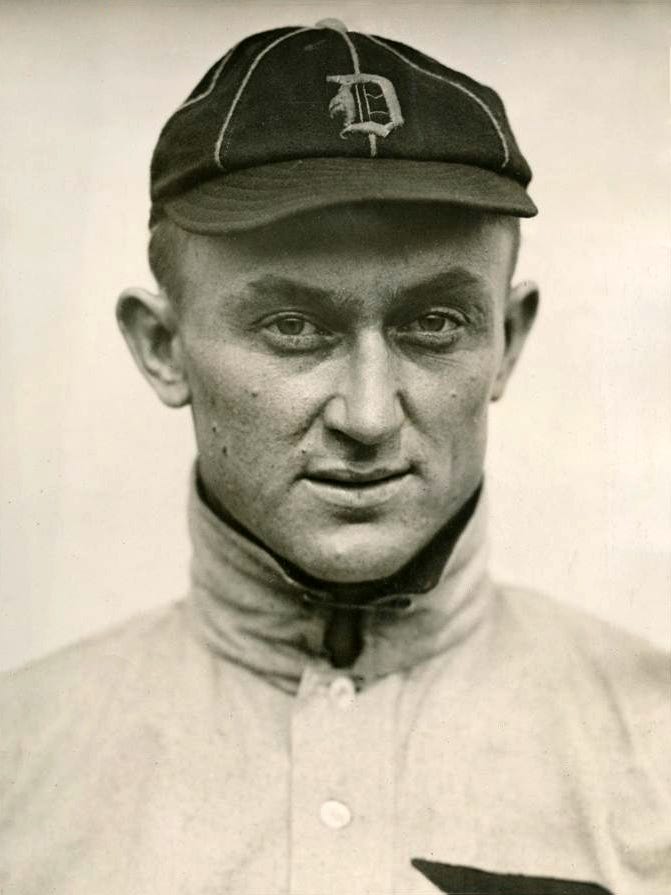

Among the legends of the game, several were Freemasons. Ty Cobb, inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1936, was a member of Royston Lodge No. 426 in Detroit. Known for his precision and aggression on the field, Cobb reflected Masonic values of discipline, ambition, and mastery. His father served as Master Mason of the same lodge, showing how Masonic heritage often carried from one generation to the next.

From its foundation to its form, baseball is a game of geometry, hierarchy, and ritual. The diamond is the temple floor, the bases are the degrees of progress, and the home plate is the return to origin. Fans may see a game of bats and balls, but beneath the surface lies a grid of symbols and measures drawn from a much older tradition.

Basketball: Court of Geometry and Status

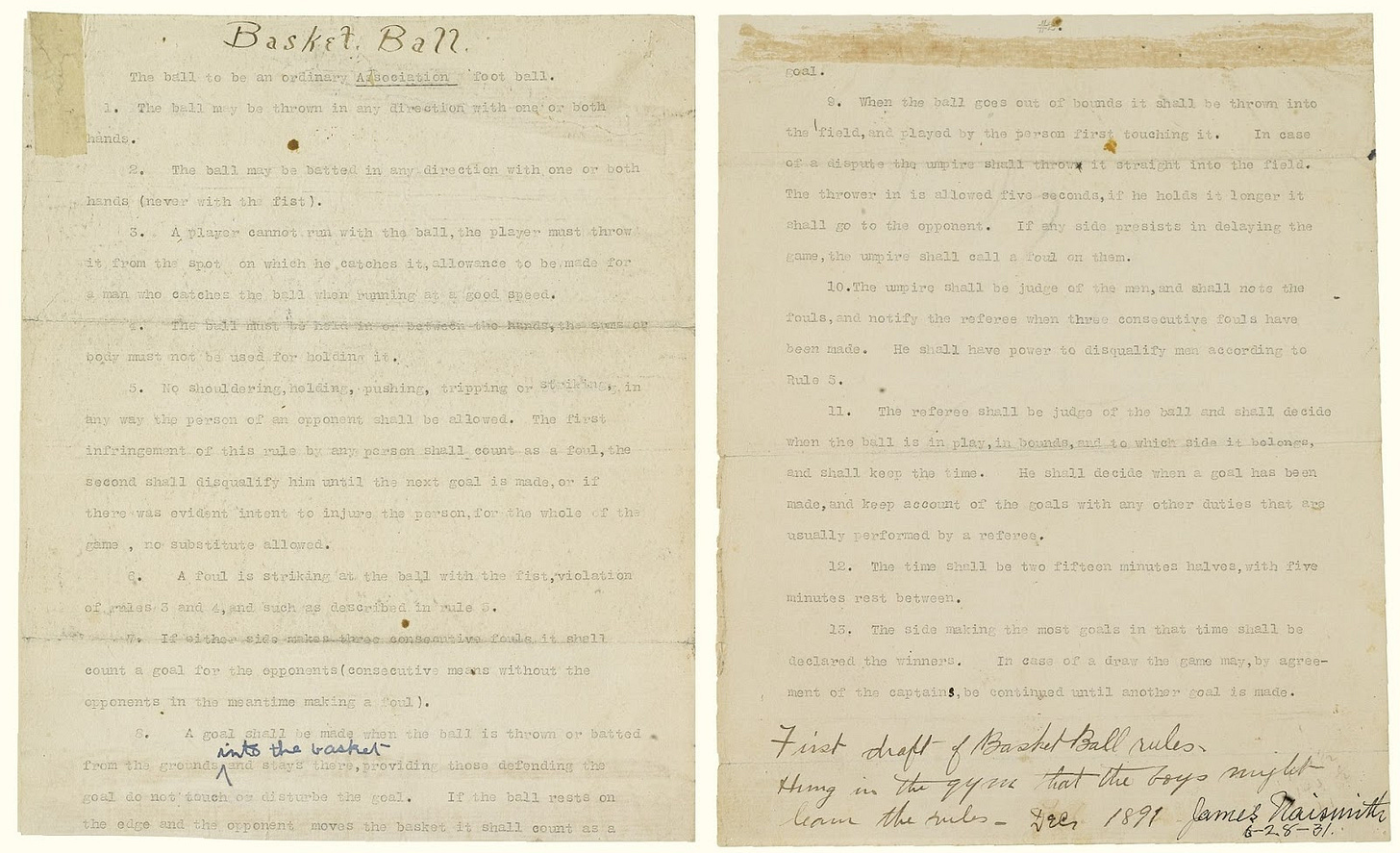

Invented by James Naismith, a Freemason, basketball reflects lodge principles. Court dimensions, the hoop’s placement, and play progression mirror ritual and geometry.

Brother James Naismith

“I am sure that no man can derive more pleasure from money or power than I do from seeing a pair of basketball goals in some out of the way place.” – Dr. James Naismith

In the annals of sports history, Dr. James Naismith inadvertently carved out a prominent place for himself as the visionary educator and inventor credited with birthing the game of basketball. A member of our venerable fraternity, Naismith’s legacy extends far beyond the hardwood courts, where his creation has become a global phenomenon. We’re proud to say Brother Naismith became a Freemason when he joined Russell Lee Lodge in Springfield, Massachusetts, in 1894 and later affiliated with Lawrence Lodge No. 6 in Kansas, where he served as Worshipful Master from 1927 until 1928.

As a Freemason, Worshipful Brother Naismith found inspiration and guidance within the principles of the craft, and it is through this lens that we can gain a deeper understanding of the man behind the game. His journey, marked by intellect, discipline, inclusivity, and a commitment to community, reflects the very essence of Masonic ideals.

Sports and Theology

James Naismith was born on November 6, 1861, near Almonte, Ontario, Canada, to a Scottish couple, John Naismith and Margaret Young. He attended grade school at Bennie’s Corners near Almonte while spending much of his time playing games outside. One game he frequently played was called Duck on a Rock and is thought to have later served as his inspiration for basketball. In this game, a large stone (the “duck”) is placed upon a larger stone or a tree stump. One player protects the stone while opposing players throw stones at the “duck” to knock it off the platform. Naismith discovered that a soft lobbing shot was far more effective than a straight hard throw, and thus, he unintentionally sowed the seed of basketball.

In 1873, young James was orphaned following the death of his parents and maternal grandmother, sending him to live with his uncle Peter Young. After high school, Naismith attended McGill University in Montreal, where he earned a BA in Physical Education and took up football, rugby, lacrosse, and gymnastics. James then entered the Presbyterian College of Theology in Montreal and graduated in 1890. He then departed for America to work at Springfield College in Massachusetts to work in physical education under Luther Halsey Gulick, the father of physical education in the United States.

The Birth of Basketball

The following year, Gulick had stressed to his faculty that the school needed a new indoor game, “that would be interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.” One rainy day in December, Naismith delivered upon Gulick’s request in an attempt to keep his gym class active. He pulled together different aspects of popular sports (as well as his childhood game “duck on a rock”), such as the passing of American rugby, the use of a goal in lacrosse, and the size and shape of a soccer ball.

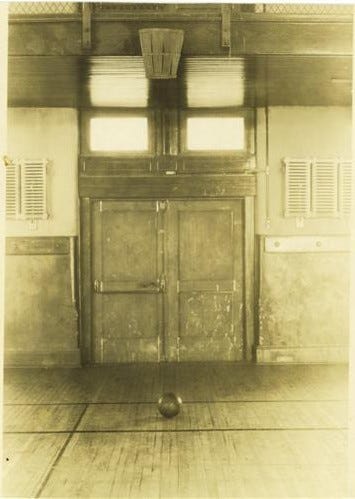

Naismith wanted, “a goal with a horizontal opening high enough so that the ball would have to be tossed into it, rather than being thrown.” He requisitioned two peach baskets from the college janitor, nailed them to the gymnasium balcony, and drew up the 13 original rules. After several years of using a long dowel after each scored basket to retrieve the ball, they cut the bottoms from the peach baskets to simplify the process. The first game was played with a soccer ball and consisted of two 15-minute halves with a five-minute intermission. The teams comprised three centers, three forwards, and three guards per side.

Years later in January 1939, Naismith gave more details of the first game and the initial rules that were used:

“I showed them two peach baskets I’d nailed up at each end of the gym, and I told them the idea was to throw the ball into the opposing team’s peach basket. I blew a whistle, and the first game of basketball began. … The boys began tackling, kicking, and punching in the clinches. They ended up in a free-for-all in the middle of the gym floor. [The injury toll: several black eyes, one separated shoulder, and one player knocked unconscious.] “It certainly was murder.” [Naismith changed some of the rules as part of his quest to develop a clean sport.] The most important one was that there should be no running with the ball. That stopped tackling and slugging. We tried out the game with those [new] rules (fouls), and we didn’t have one casualty.”

Meet Coach Naismith

Over time, soccer balls were phased out of the game and eventually replaced today by the modern basketball. The school hosted the first public basketball game on March 12, 1892, and saw over 200 spectators in the crowd. Within two years, basketball had grown so popular that the YMCA spread it internationally. Soon, dribbling was introduced, and the game evolved to resemble more closely what we know today as basketball. Whereas passing was the original way to advance the ball, dribbling was part of the game by 1896.

During this period, James married Maude E. Sherman and started a family that would include five children: Margaret, Helen, John, Maude, and James. With the true mind of a Freemason, Naismith continued his pursuit of greater learning. He soon left Springfield for Denver to obtain his medical degree before joining the University of Kansas faculty in 1898. Naismith served as the gymnasium director and campus chaplain in his new role. He also introduced basketball and served as the school’s coach.

A True Freemason

By 1906, the peach baskets had been replaced by metal hoops with backboards, and enough college teams had formed to establish the first intercollegiate competitions. Basketball continued to gain popularity, but Naismith preferred gymnastics and wrestling to his creation. He served as the athletic director at Kansas for much of the early 20th century and became an American citizen on May 4, 1925.

When we consider basketball’s influence on the world, it’s no surprise that it is considered Naismith’s crowning achievement. But during his time in Kansas, he fought for something more important: equality. He detested segregation and fought for progress in race relations in his small corner of the world. Throughout the 1930s, he strove to get black students onto Kansas’ varsity Jayhawks but was unsuccessful. However, he did help end the segregation of the university’s swimming pool.

Legacy and Awards

We’re glad to say that when Worshipful Brother Naismith was 74, he witnessed the introduction of basketball into the official Olympic sports program of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games in Berlin. It was a tremendous and well-deserved honor. He passed away in 1939 at 78, eight months after the NCAA Basketball Championship was established. Today, it is one of the biggest sports events in North America.

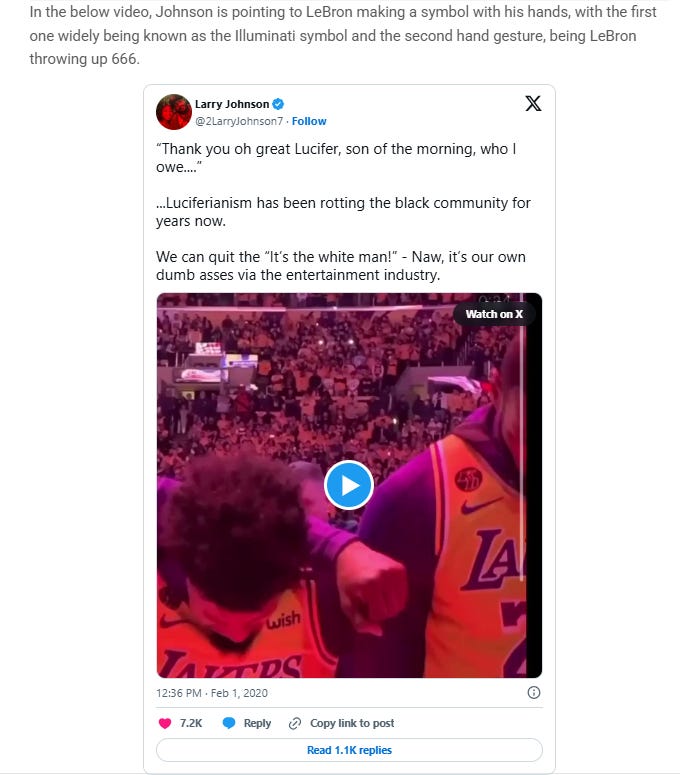

If Dr. Naismith’s goal was to help people develop character and improve society through sport, he certainly succeeded. Over a century after it was created, basketball is now played in over 200 countries by more than 300 million people. It is among the most popular team sports in the world and has given rise to some of the most well-known and admired athletes, including Ohio’s own LeBron James, John Havlicek, Stephen Curry, Nate Thurmond, and Jerry Lucas.

Modern basketball generates billions annually. Players such as Shaquille O’Neal, a 7-foot-1 Prince Hall Mason, openly display Masonic rings, signaling their integration into elite networks that extend far beyond the court.

When you start looking closer, sports reveal hidden layers and connections to Freemasonry that often go unnoticed. It makes you wonder what the real purpose behind America’s so-called favorite pastimes is.

Game, Set, Match: Influence Beyond the Field

Freemasons have been athletes, organizers, and cultural influencers. Ty Cobb and Shaquille O’Neal have each left a mark on sport while reflecting fraternity values or networks. But the deeper story is one of power, structure, and influence. The fields, courts, diamonds, and greens are more than games: they are ritualized stages for wealth, hierarchy, and symbolism, guided by networks that extend far beyond what fans see. So next time you watch a match, pitch, or tee shot, ask: Who really set the rules? Who profits? And what hidden rituals shape the spectacle?

![Football Square & Compass Masonic Lapel Pin - [Blue White][5/8'' Tall] : かめよしエクスプレス - 通販 - Yahoo ... Football Square & Compass Masonic Lapel Pin - [Blue White][5/8'' Tall] : かめよしエクスプレス - 通販 - Yahoo ...](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!AF_Q!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F4c9df474-e550-4bf7-80fc-3c3a21f224fb_713x763.jpeg)

![Baseball ball - Download Free 3D model by 3dartstevenz [50314b8] - Sketchfab Baseball ball - Download Free 3D model by 3dartstevenz [50314b8] - Sketchfab](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ijmX!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fb80c4e9c-4028-40bf-b790-433cf2660aa3_474x266.jpeg)

In the Richard Day Tapes one item was discussed was to eliminate American football over time in favor of soccer.

216 is of course 6 x 6 x 6