Plagues and Power

Unraveling the Possibilities of Plagues, Epidemics, and Pandemics as Engineered Resets

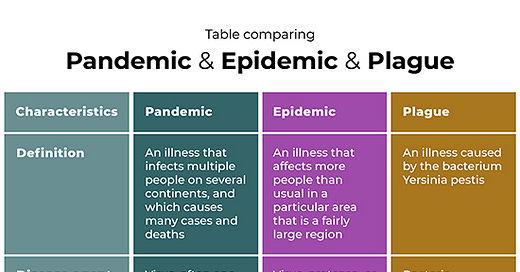

Throughout recorded history, plagues, epidemics, and pandemics have ominously intertwined with resets in politics and religion. Plagues are believed to be highly infectious diseases historically associated with devastating local outbreaks, often linked to diseases like the bubonic plague. Epidemics are thought to occur when the occurrence of a disease within a specific community or region exceeds expected levels, resulting in a sudden surge in cases and strain on healthcare systems. Pandemics are purported to be epidemics that spread across multiple countries or continents, affecting a large number of people globally and necessitating coordinated international responses to control and mitigate their impact.

These catastrophic outbreaks frequently precede or accompany significant shifts in societal norms and power dynamics, prompting eerie correlations between disease and profound social change. While some speculate about nefarious intent behind using pandemics to maintain control or pursue hidden agendas, it's crucial to approach such claims with skepticism and consider historical complexities.

Yet, the unsettling coincidence prompts reflection on the interplay between disease, power, and human history, suggesting potential manipulation of crises to reset populations and control the masses under the guise of public safety. The question arises: Is this a way for those in power to facilitate resets without the awareness of the masses, perpetuating a cycle of control and societal transformation?

During the Golden Age of Greece in 430 BCE, one of the earliest recorded plagues struck the city-state of Athens, posited by mainstream narratives that it was caused by typhus, typhoid, or smallpox, possibly originating from Ethiopia and spreading through North Africa. This outbreak occurred during the 2nd Peloponnesian War against Sparta, leading to the collapse of public safety measures as Athenians, believing they wouldn't survive, disregarded the laws. The historian Thucydides, who survived the plague, documented the societal breakdown and rise in self-indulgence while dismissing rumors that the Spartans had poisoned Athens' water supply. Thucydides, an Athenian general and historian, is renowned for his work "History of the Peloponnesian War," which provides a detailed contemporary account of the war and the plague.

The plague struck in two waves, the first being more deadly, and it claimed the life of Athenian leader Pericles, who had ordered a retreat behind the city’s walls, inadvertently worsening the spread. With no known remedy, Thucydides expressed hope that future generations would combat such epidemics through knowledge and science. The plague significantly weakened Athens, tipping the war in Sparta’s favor and marking a turning point in Athenian democracy. Given its timing and impact, some question the true origins of the plague, drawing parallels to other pandemics that have shifted political landscapes, suggesting a pattern that seems rather suspicious.

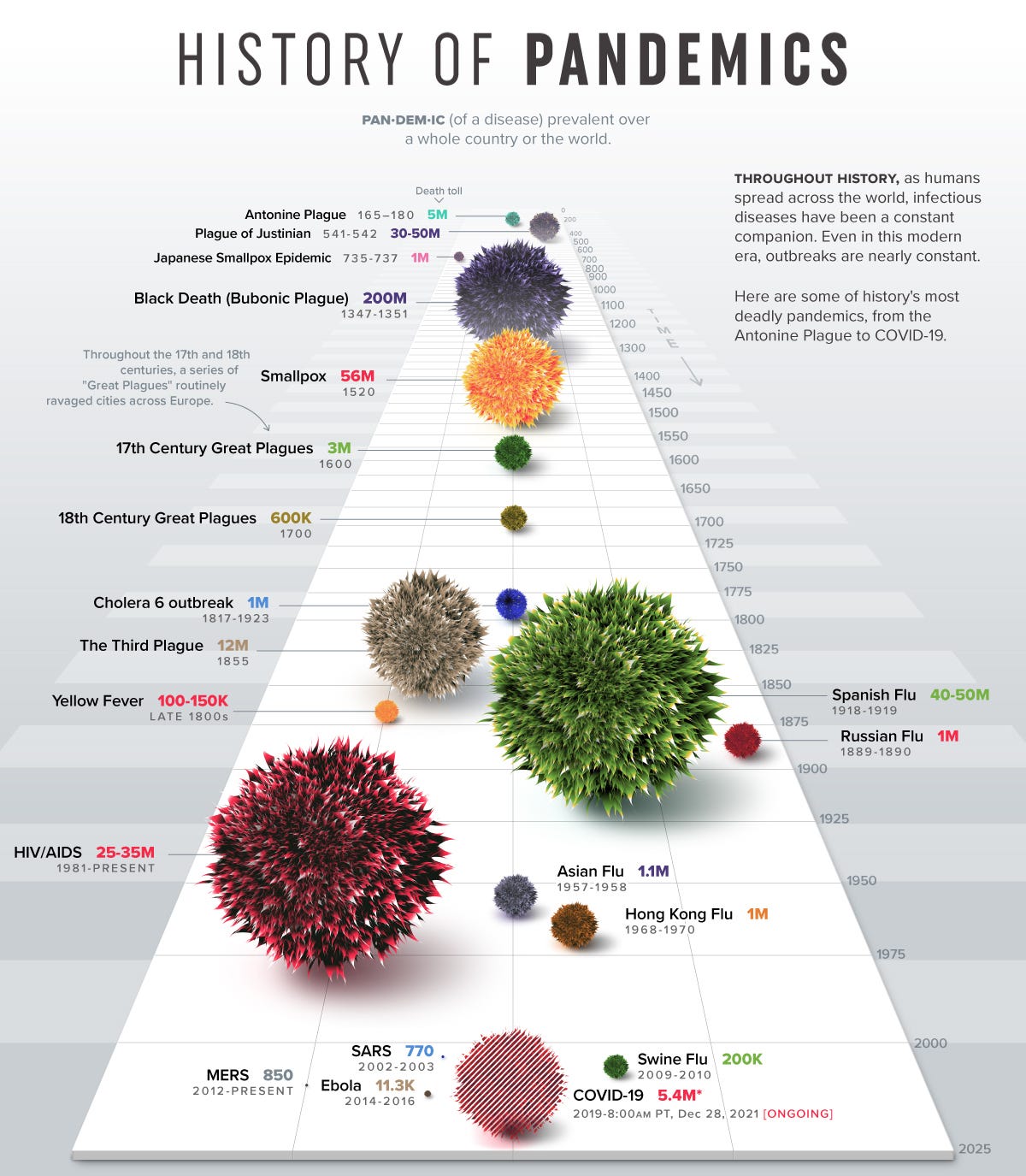

Similarly, the Antonine Plague (165-180 CE), thought to have been caused by smallpox or measles, ravaged the Roman Empire, killing up to five million people, including the co-emperor Lucius Verus.

The plague resurfaced 15 years later, further weakening the empire. While the mainstream explanation revolves around germ theory, Marcus Aurelius's blame of Christians for the plague due to their rejection of Roman gods suggests a deeper political and religious conflict. Could there have been another overlooked instance of deliberate poisoning? This raises doubts about the reliability of the historical narrative and the likelihood of it being potentially biased and heavily censored. Despite imperial persecution, Christians' dedication to caring for the sick elevated their status among Romans, fueling the growth of Christianity. The societal consequences were significant, ending the Pax Romana and indicating a decline in Roman power and stability, notably within its military.

Marcus Aurelius’s "Meditations" reflected his belief in the cyclical nature of history, acknowledging that such calamities had occurred before and would likely recur. The Antonine Plague, akin to the devastation of the Plague of Athens, dealt a severe blow to Rome's military, particularly along its eastern and northern borders, allowing Germanic and Gallic tribes to advance southward.

Historian Edward Gibbon, in "The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire," pointed to pestilence and famine as pivotal factors in Rome’s decline. Without any effective treatment or cure available (because no one really knew then or now what was really making people sick), the Antonine Plague significantly contributed to the empire's eventual downfall. Oh, but don't worry, because a magical solution emerged 1600 years later: vaccines! Now people can inject themselves with what could very well be poison and call it a cure. It makes you wonder about the true nature of the event and its impact on reshaping Roman society, doesn't it?

Another significant event, the Plague of Cyprian (250-271 CE), is believed to have caused widespread mortality, contributing to the crisis of the Third Century in the Roman Empire. The emergence of the Plague of Cyprian in Ethiopia around 250 CE, swiftly spreading to Rome, Greece, and Syria within a year, marked a devastating chapter in history. Persisting for nearly two decades, it resulted in an alarming daily death toll of up to 5,000 in Rome at its zenith. The plague's impact was exacerbated by ongoing conflicts, environmental catastrophes, and political unrest, prompting St. Cyprian to draw parallels to an apocalyptic scenario.

Named after the bishop of Carthage, the plague's exact cause remains uncertain, with hypotheses ranging from smallpox to viral hemorrhagic fever like Ebola. Cyprian's detailed accounts depict a society ravaged by illness and societal collapse, underscoring the profound ramifications of the epidemic's spread across the empire. Despite ongoing debates among historians regarding its precise nature, the Plague of Cyprian left an indelible imprint on Roman society, contributing to further political instability, military weakening, and societal disruption.

Amidst the turmoil, the steadfast dedication of Christian clergy in tending to the afflicted played a pivotal role in attracting converts and propagating Christianity throughout the empire, exemplifying the resilience of faith in the face of adversity. The enduring legacy of the Plague of Cyprian serves as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of civilizations to pandemics, reshaping historical trajectories and leaving a profound impact on Roman civilization. Yet again, amidst this chaos, suspicious events unfolded, altering history's course, with the true cause of these calamities remaining elusive and shrouded in mystery.

The Plague of Justinian (541-750 CE) is generally believed to have been caused by Yersinia pestis, bringing recurring waves of bubonic plague that killed millions, severely impacting the Byzantine Empire’s population and economy. The Plague of Justinian began during the reign of Emperor Justinian I, who ruled the Eastern Roman Empire from 527 AD until his death in 565 AD. Near the end of the plague, Justinian I was still in power, overseeing the empire's response to the ongoing crisis.

The plague that swept through the Eastern Roman Empire in 541 AD is asserted to be the Bubonic Plague, caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, the same pathogen responsible for the devastating Black Death nearly eight centuries later. While researchers have suggested a genetic connection between Justinian's strain and the later outbreak, uncertainties remain. If DNA analysis proves accurate, it suggests the Plague of Justinian left behind a precursor to another strain, potentially leading to the emergence of a new, equally deadly variant. Despite its presence in over 200 species of rodents worldwide, direct scientific evidence linking this bacterium to human illness remains inconclusive, underscoring the importance of discernment when interpreting historical accounts of pandemics.

The Plague of Justinian exacted a staggering toll, estimated at 30 to 50 million deaths, which represented nearly half of the world's population at the time. This catastrophic loss of life left indelible marks on the affected regions, reshaping demographics and cultures irreversibly. The pandemic triggered labor shortages, disrupted trade, and inflicted lasting psychological trauma on survivors. It catalyzed profound shifts in societal structures and religious beliefs, fundamentally altering the fabric of the society for generations to come.

Politically and religiously, the plague wrought significant changes. It weakened the Eastern Roman Empire's central authority, leading to political instability and social turmoil. Religious institutions grappled with the pandemic, attempting to explain its cause and mitigate its effects through prayer and rituals, thus influencing the broader societal relationship with religion. The Plague of Justinian stands as a pivotal moment in history. But does anyone really know what really happened or why? Like the previous pandemics, the historical “facts” and scientific consensus about this occurrence seem to be nothing more than conjecture.

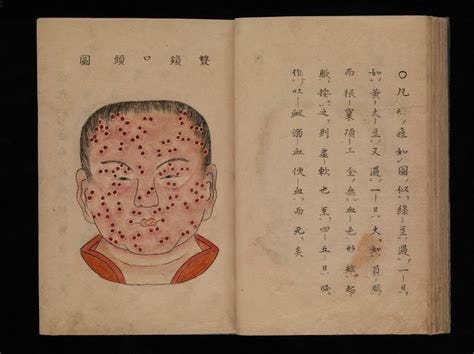

The Japanese smallpox epidemic of 735-737, thought to have been introduced via the Korean Peninsula, devastated the country, killing about one-third of the population. This high mortality rate led to severe labor shortages and agricultural decline, causing economic instability and famine. The epidemic particularly affected urban centers like Nara, and the central government, led by Emperor Shōmu, struggled to manage the crisis, leading to a loss of confidence in imperial rule. In response, religious activities surged, with Emperor Shōmu promoting Buddhism to appease the gods, resulting in the construction of significant Buddhist temples such as Tōdai-ji.

The long-term effects of the epidemic were profound, reshaping Japan's social, political, and religious landscape. Buddhism's prominence grew, deeply influencing Japanese culture and religion. The crisis also exposed the central government's vulnerabilities, leading to administrative changes and an increase in the power of local aristocrats and regional officials. These developments had lasting impacts on the governance and cultural fabric of Japan, marking the epidemic as a pivotal event in the nation's history.

According to Germ Theory, the epidemic was caused by the Variola virus, responsible for smallpox, which spread through respiratory droplets and direct contact. However, alternative explanations suggest that environmental factors, such as climatic changes and the presence of toxins, could have also played a significant role. For instance, heavy metals like mercury and lead, along with natural toxins such as aflatoxins and ergot, might have contaminated food and water supplies, leading to chronic health issues.

Climate change, including periods of cooling and drought, likely exacerbated food shortages and weakened the population's immune systems, making them more susceptible to disease. Spiritual beliefs attributed the outbreak to divine punishment or malevolent spirits, prompting increased religious activities. While historical evidence strongly supports smallpox as the primary cause, considering these environmental and climatic factors provides a more nuanced understanding of the epidemic's severity and its profound impact on Japanese society.

The infamous Black Death plague (1347-1351), is asserted to have be caused by the same bacterium thought to have caused the deaths of an estimated 25-50 million people (reports vary on how many it killed), roughly one-third of Europe's population, reshaping the continent’s demographic and social structure. The cause of the pandemic remains uncertain, shrouded in conjecture about the countless lives it impacted and the reasons behind its occurrence.

Before germ theory made its major debut, healthy individuals would employ three strategies to limit contagion during epidemics and pandemics: physical distancing from the infected, quarantine measures such as the Venetian practice of isolating travelers for forty days upon arrival, and isolation of known infected individuals from the healthy population, as seen during the Great Plague of London in 1665 when the sick were sent to the countryside.

The aftermath of the Black Death brought profound economic changes, including a two-century recovery period for Europe's population and a shift in the labor market, with increased demand and higher wages for laborers. The pandemic also led to extreme inflation due to disruptions in trade and production. Various factors contributed to mitigating the impact of the Black Death, including relocation of the wealthy, quarantine measures, natural weather changes, and the destruction of rat populations by events like the Great Fire of London. Say what? Interestingly, this period made the rich (like the Medici family) even richer. Totally nothing to investigate here, right?

The impact of the Black Death was particularly severe on the poor, who often lived in crowded and unsanitary conditions, making them more vulnerable to disease transmission. Many poor individuals worked in occupations involving close contact with others, such as laborers, servants, and artisans, further increasing their risk of exposure. The economic repercussions disproportionately affected them, as disruptions in trade and production led to widespread unemployment and food shortages, exacerbating their already precarious living conditions. Considering these factors, one might question whether the devastating effects of the Black Death were inadvertently or intentionally targeted at the poor. Was this pandemic, which disproportionately affected the lower socioeconomic classes, a deliberate move to cull the population of the impoverished?

The smallpox epidemic of the 1500s devastated indigenous populations in the Americas, starting with outbreaks in Hispaniola in 1518 and spreading rapidly to Central and South America by the 1520s. The virus, Variola major, caused fever, vomiting, and distinctive skin rashes, leading to severe scarring and, in many cases, death. Germ theory, which emerged in the 19th century, identified the variola virus as the cause of smallpox, replacing earlier explanations like miasma theory or divine punishment.

The impact of the epidemic was profound, with up to 90% of indigenous populations perishing. This demographic collapse facilitated European conquest and colonization by weakening and destabilizing indigenous societies. Survivors often “assimilated” into European-controlled societies, leading to a significant cultural and societal shift. The pandemic also prompted early public health responses, such as quarantine and isolation practices, laying the groundwork for modern epidemiological practices.

While theories of intentional genocide or chemical warfare have been proposed, the exact circumstances surrounding the spread of smallpox in the Americas remain uncertain. Despite the widespread devastation supposedly caused by smallpox, the catastrophic consequences of the pandemic on indigenous populations and its pivotal role in reshaping the course of history are undeniable. Is it plausible to attribute the genocide of numerous people solely to natural causes, or does this narrative serve as a sanitized version of history, absolving the responsible parties of accountability for the deaths of millions?

The Great Plague of London, occurring between 1665 and 1666, and the Marseille plague outbreak in 1720 collectively resulted in an estimated death toll of around 200,000 people (but some accounts are up to 3-4 million deaths). These devastating epidemics decimated populations in London, England, and Marseille, France, with each claiming roughly 100,000 lives, representing a significant portion of the affected cities' populations at the time.

During the 17th and 18th centuries, marked by overcrowded urban centers, poor sanitation practices, and limited medical or scientific understanding, these outbreaks thrived. Factors such as dense populations, inadequate waste disposal systems, and the presence of rats and fleas facilitated the spread of disease, which was believed to be caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis.

The societal impact of these plague outbreaks was profound, instilling fear and panic among the populace and leading to social disruption, economic hardship, and widespread mourning.

In response to the devastation caused by these epidemics, efforts were made to improve public health infrastructure, sanitation practices, and disease prevention measures in the following years. Despite being associated with Yersinia pestis, conclusive evidence pinpointing it as the sole cause of these specific outbreaks remains lacking.

The Third Cholera Pandemic (1852-1860), the deadliest of seven cholera outbreaks, is believed to have spread across multiple continents, killing over a million people. This pandemic, thought to originate in India in the 19th century, spread globally, causing devastating outbreaks. In Russia, over one million deaths were attributed to cholera. In London, the epidemic of 1853-1854 claimed over 10,000 lives, with a total of 23,000 deaths reported across Great Britain.

The Cholera outbreak of the 1800s spurred significant political and religious reforms, particularly in the realm of public health policy. Cholera is thought to be caused by the ingestion of water or food contaminated with the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. In response to the crisis, governments implemented reforms aimed at improving sanitation infrastructure and public health measures. In London, for example, the outbreak led to the establishment of the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers and the construction of the London sewer system under the direction of engineer Joseph Bazalgette. Religious organizations also played a role, with some churches and religious leaders advocating for improved hygiene practices and sanitation to prevent the spread of disease.

The exact number of deaths resulting from the Cholera outbreak of the 1800s is difficult to determine due to limited record-keeping and varying reporting practices at the time. However, it is estimated that tens of thousands of people died during the outbreaks, particularly in densely populated urban areas where the disease spread rapidly.

Cholera symptoms typically include severe diarrhea, vomiting, and dehydration, and the disease can be fatal if left untreated due to severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances resulting from profuse diarrhea and vomiting.

While there is no conclusive evidence to support the theory that the water was intentionally poisoned during the Cholera outbreaks, rumors and suspicions of foul play were common during the time. Some believed that the outbreaks were caused by deliberate contamination of water sources by political or religious adversaries. Historical evidence does not support these claims, but it does not disprove it either, and the consensus among historians and public health experts is that the outbreaks were primarily the result of poor sanitation and hygiene practices.

Other explanations for why people were becoming ill during the Cholera outbreaks include theories related to miasma, the belief that diseases were caused by foul-smelling air emanating from decomposing organic matter. However, with the advancement of germ theory in the latter half of the 19th century, it became increasingly clear that the transmission of Cholera was primarily through contaminated water and food, rather than through airborne pathogens.

The third plague pandemic began in the Yunnan province of China in the 1850s and spread globally by the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It reached Hong Kong in 1894, becoming a key point for international dissemination via steamships. This pandemic affected numerous regions, including India, Southeast Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe, and the Americas, with India suffering the most severe impact, losing over 10 million people to the disease.

The pandemic had profound social and economic impacts on the affected regions. Cities faced significant population losses, leading to labor shortages and economic downturns. Trade was disrupted as ports and markets closed to prevent the spread of the disease. Quarantine measures and travel restrictions were widely implemented, affecting global movement and commerce. Public health responses, such as improved sanitation, pest control, and isolation of patients, became more systematic, laying the groundwork for modern public health practices.

This pandemic overlapped with other historical plague outbreaks, such as the Justinian Plague and the Black Death, and was attributed to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. It reaffirmed the germ theory of disease, which was gaining acceptance at the time, attributing the spread to fleas on rats. However, other theories, including miasma (bad air) and intentional poisoning, were still prevalent. Politically, inciting illness could weaken enemy populations, create economic instability, or justify military and colonial interventions by suggesting that native populations were unhygienic and needed control. This context highlights the intertwining of disease, scientific understanding, and political motives during the era.

During this period, European colonial powers, particularly Britain and France, were expanding their control over many poorer countries in Africa and Asia. They often used public health crises as a pretext to strengthen their grip on these regions, implementing strict quarantine and sanitation measures that sometimes disrupted local economies and societies.

The pandemic exposed and often exacerbated existing social inequalities, as poorer communities suffered disproportionately due to inadequate access to medical care and living in unsanitary conditions. These interventions were sometimes viewed with suspicion and resistance by local populations, who saw them as an extension of colonial domination.

In the late 1800s, supposed yellow fever outbreaks wreaked havoc on cities throughout the Americas, leaving devastation in their wake. Notably, Memphis, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana, experienced significant outbreaks, adding to a recurring pattern of epidemics that plagued the region during that era. These outbreaks unfolded in the aftermath of the American Civil War, a conflict that had profoundly divided the nation and left it in a fragile state. As the nation grappled with reconstruction efforts and attempted to recover from the war's toll, the subsequent yellow fever epidemics further compounded its challenges.

The impact of the yellow fever outbreaks on political outcomes varied across different regions affected by the disease. In cities like Memphis and New Orleans, where the outbreaks were particularly severe, they strained local governance structures and overwhelmed public health systems. The authorities' inability to effectively contain the disease's spread heightened public discontent and unrest, exacerbating the already fragile post-war situation.

Yellow fever, characterized by symptoms such as fever, jaundice, and internal bleeding, was thought to spread primarily through the bite of infected mosquitoes, particularly Aedes aegypti. While the germ theory of disease was gaining traction, other explanations persisted. Miasma theory, for instance, attributed diseases like yellow fever to "bad air" or environmental factors, a belief that prevailed in some circles despite emerging scientific understanding.

The outbreaks of yellow fever in the late 1800s had devastating death tolls, claiming thousands of lives. Such epidemics triggered widespread panic and social unrest as people fled afflicted cities to escape the disease's grasp. Politically, these crises often sparked tensions between local and federal authorities, fueling debates over public health strategies and quarantine measures. These outbreaks presented opportunities for power shifts and manipulation. Certain individuals or groups could exploit the chaos to consolidate their influence or push forward political agendas. Economic repercussions were profound, with trade and commerce disrupted, leading to financial losses and economic downturns in affected regions. Socially and religiously, some interpreted the epidemics as divine retribution or spiritual warnings, sparking religious fervor and calls for repentance.

These outbreaks mirrored pandemics of the past in their capacity to alter power dynamics. Those in positions of authority could leverage the crises to enhance their control, while marginalized groups faced heightened vulnerability. The economic fallout reshaped commercial landscapes, with some benefiting from the upheaval while others suffered. Ultimately, the yellow fever outbreaks of the late 1800s yet again highlights the profound societal impacts of purported infectious diseases and the potential for such crises to shape political, economic, and religious landscapes.

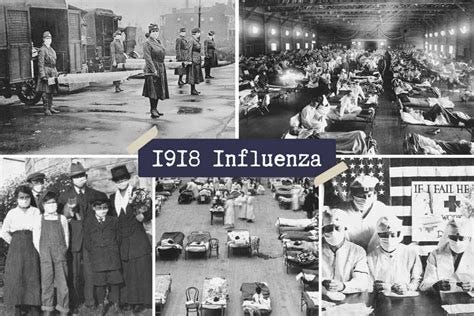

The Spanish flu, a deadly influenza pandemic, emerged during the closing stages of World War I, spreading across the globe from 1918 to 1919. It affected virtually every corner of the world, with an estimated 500 million people – about one-third of the global population – being infected. The virus caused unprecedented mortality rates, claiming the lives of an estimated 50 million people worldwide.

According to the prevailing Germ Theory of Disease, the Spanish flu was caused by the H1N1 influenza virus. Alternative theories have been proposed, including environmental factors such as poor sanitation and overcrowding in military camps and urban areas, which may have facilitated the spread of the disease. The pandemic had profound societal impacts, overwhelming healthcare systems and causing widespread fear and panic. It also altered societal norms, with public gatherings restricted and mask-wearing becoming commonplace in many regions. While the pandemic was a natural occurrence, certain industries, such as pharmaceutical companies and healthcare providers, may have benefitted from increased demand for medical supplies and services.

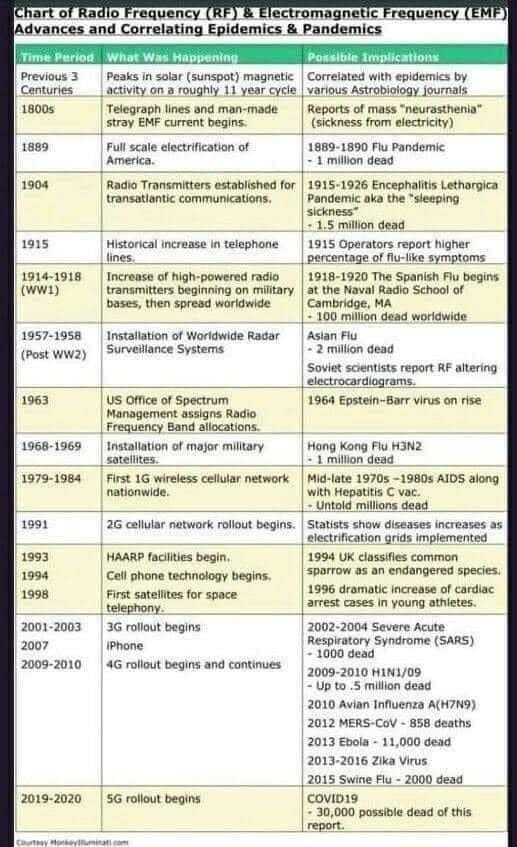

After examining numerous instances of intense outbreaks of illness with dire consequences for populations and society, and considering various theories regarding the causes of illnesses and symptoms, one notable absence from the mainstream narrative becomes apparent: the potential influence of "solar electromagnetic pollution" and "electric smog," whether natural or generated by man-made sources, on the occurrence of plagues, epidemics, and pandemics. Could there be individuals who possess this hidden scientific knowledge and exploit it to wield power and control over others (maybe hidden underneath the vast Vatican libraries locked away from public view or under classified areas around the world)? This raises thought-provoking questions about the impact of "solar electromagnetic pollution" and "electric smog," on human health and the potential ramifications for the spread and severity of infectious diseases.

Throughout history, plagues, epidemics, and pandemics seem to have coincided with periods of heightened solar activity, suggesting a potential link between celestial phenomena and human health. Solar flares, intense bursts of radiation from the sun, are a notable aspect of this activity and have been associated with various health impacts on Earth.

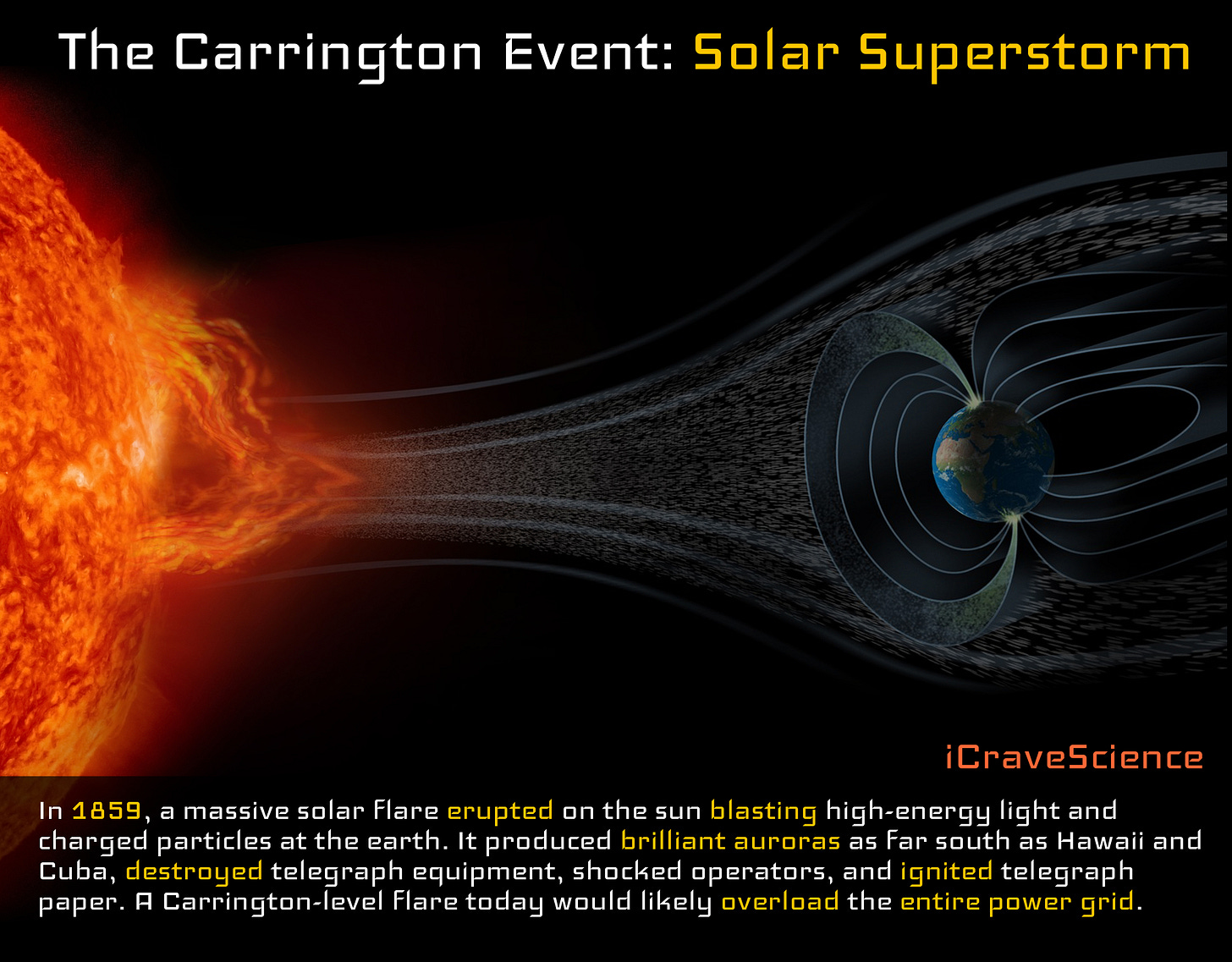

For instance, in 1859, alongside the third cholera pandemic, occurred the Carrington Event, a significant solar disturbance named after British astronomer Richard Carrington. This event unleashed a powerful solar storm with a massive coronal mass ejection (CME), sending solar particles and electromagnetic radiation towards Earth.

The Carrington Event disrupted telegraph systems globally and caused auroras to be visible as far south as the Caribbean. Some researchers suggest a possible connection between solar events like the Carrington Event and human health. They theorize that the influx of solar particles and radiation may disturb Earth's electromagnetic environment, potentially impacting biological processes and exacerbating certain health conditions. Although direct evidence linking solar events to illness is lacking, the Carrington Event highlights the complex interplay between celestial phenomena and life on Earth, prompting further investigation into the potential health impacts of solar activity.

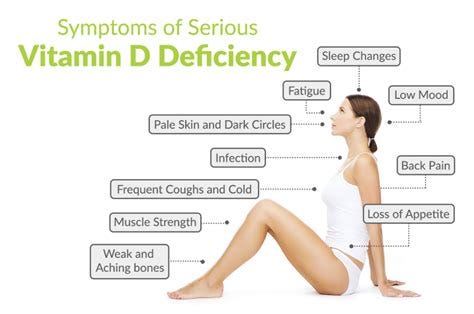

But why would this have an impact on human health or well-being? Solar flares can disrupt Earth's magnetic field and impact atmospheric conditions, potentially affecting human physiology and disease transmission dynamics. Changes in geomagnetic activity may influence human immune function. Solar radiation, including ultraviolet (UV) radiation from solar flares, can affect human health by altering vitamin D levels and potentially increasing susceptibility to various health conditions.

Given that we are all fundamentally electrical entities, it stands to reason that such phenomena would affect our overall function and balance, wouldn't it? Exploring the intricate relationship between solar activity, solar flares, and historical disease outbreaks offers a captivating avenue for interdisciplinary research, blending epidemiology, climatology, and astrobiology to unravel the hidden influences of the cosmos on human health.

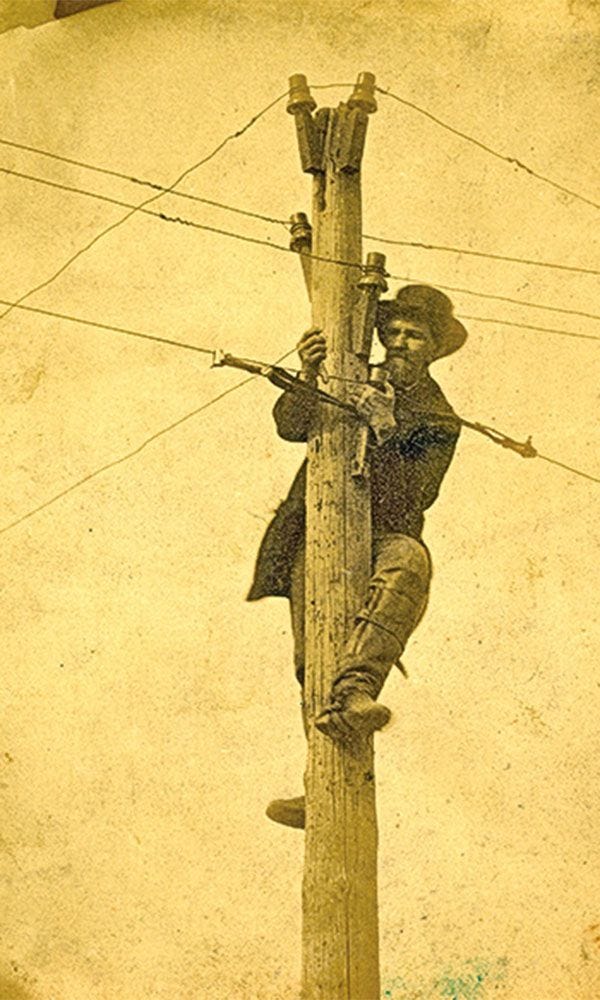

Another phenomenon that is not talked about in mainstream historical accounts is the rollout of telegraph and electricity technologies during the late 19th and early 20th centuries coinciding with the 1918 flu pandemic, sparking theories that these advancements could have directly impacted people's health and well-being.

Some researchers have proposed that exposure to electromagnetic fields generated by telegraph wires and electrical infrastructure may have had physiological effects on the human body, potentially weakening immune systems or exacerbating symptoms of respiratory illnesses like influenza.

The rapid electrification of homes and workplaces introduced new environmental factors, such as artificial lighting and increased indoor pollution from coal-fired power plants, which could have contributed to the spread or severity of the pandemic.

These theories highlight the complex interplay between technological progress and public health, suggesting that the widespread adoption of electricity may have influenced the course of the 1918 flu pandemic.

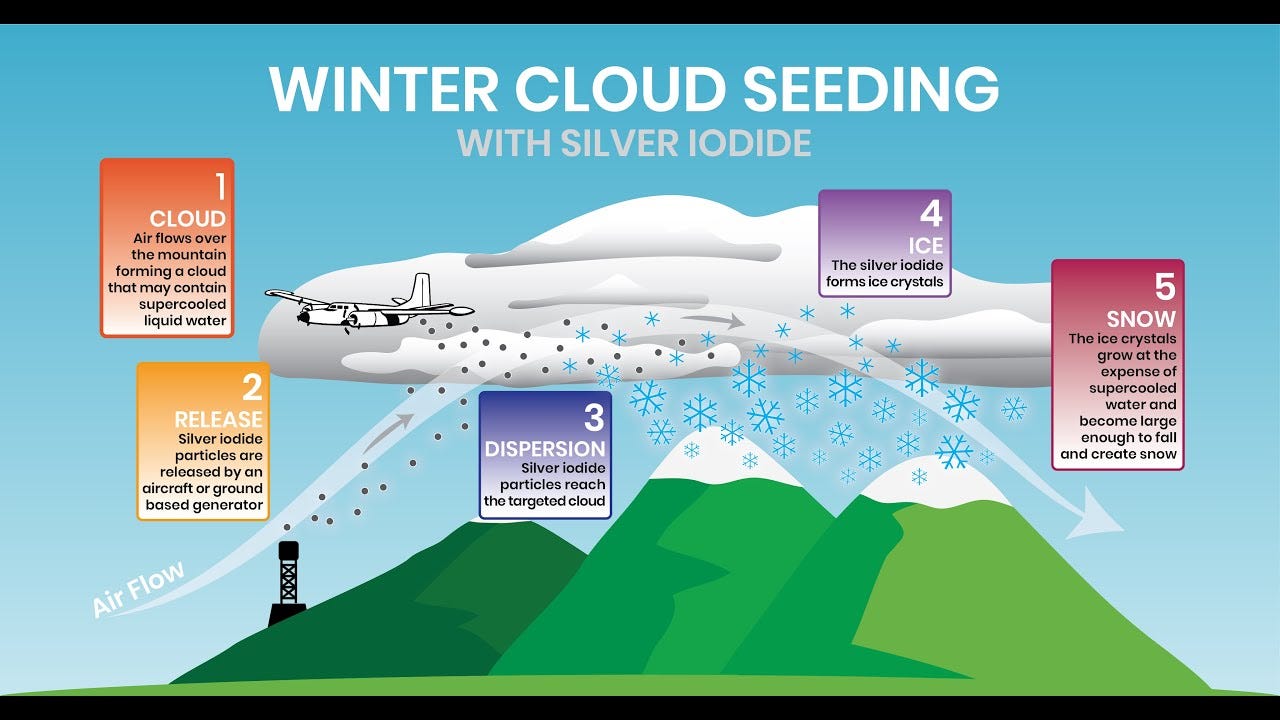

Subsequent to the 1918 flu pandemic, several influenza pandemics occurred, including the Asian Flu (1957-1958), the Hong Kong Flu (1968-1969), and the Russian Flu (1977-1978), collectively resulting in millions of deaths worldwide. Influenza, along with other respiratory illnesses, is estimated to kill hundreds of thousands of people annually. Despite its purported viral origins, there is evidence suggesting other factors, including "solar electromagnetic pollution" and "electric smog,", environmental toxins, cloud seeding, and the widespread use of substances in influenza and other vaccines. The symptoms of numerous respiratory illnesses often overlap with those of the flu, raising questions about the accuracy of diagnosis and the true nature of these diseases.

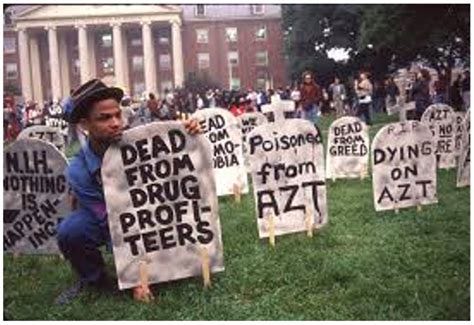

The HIV/AIDS pandemic, originating in 1981 and persisting today, has been attributed to over 32 million deaths, profoundly impacting global health and demographics. The assertion that AIDS is caused by the HIV virus was first made by Dr. Luc Montagnier and his team at the Pasteur Institute in France in 1983. However, dissenting voices, such as those of Kary Mullis, have questioned the validity of this assertion.

Stefan Lanka and others argue that no virus has ever been isolated or demonstrated to cause illness according to Koch's Postulates, the scientific gold standard for establishing causation. The diagnostic testing employed for HIV/AIDS diagnoses has also faced scrutiny for its reliability. Are contemporary outbreaks and pandemics exacerbated by fraudulent and inaccurate testing methods?

During the emergence of HIV/AIDS, the rollout of 1G wireless networks further complicated matters. These networks introduced additional electromagnetic radiation into the environment, potentially exacerbating illness among affected populations. Moreover, the lifestyle factors of many gay men during this time, characterized by drug use, excessive partying, and unprotected anal sex, may have contributed to their overall health decline. The introduction of AZT (azidothymidine), an early antiretroviral medication, further compounded health issues. AZT, initially hailed as a treatment for HIV/AIDS, had severe side effects and could potentially worsen symptoms, leading to further deterioration and even death in some cases.

The mainstream explanation for the cause of HIV/AIDS is dubious at best, raising questions about its validity. Individuals diagnosed with the condition encounter various scenarios, with some being asymptomatic yet testing positive and consequently subjected to potentially hazardous treatment protocols. Others may experience symptoms of unknown origin due to flawed diagnostic testing, leading to similar treatment approaches. The entire situation appears to be rife with fraud and suspicious motives.

From 2000 until today, several respiratory outbreaks have occurred globally. The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) outbreak emerged in China in 2002-2003, caused by SARS-CoV. Following this, the H1N1 influenza pandemic occurred in 2009, originating in Mexico and spreading rapidly worldwide. Then, the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) outbreak happened in 2012, caused by MERS-CoV, originating in Saudi Arabia. Both SARS and MERS are suggested by mainstream narratives to be viral in origin and to have likely originated in bats and transmitted to humans through intermediate hosts. SARS spread to multiple countries, while MERS primarily affected the Middle East. Alongside these outbreaks, annual respiratory illnesses such as seasonal influenza, caused by various strains of influenza viruses, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are asserted to impact populations globally each year. But much like HIV/AIDS, these illnesses are diagnosed with questionable diagnostic testing that is not reliable or accurate.

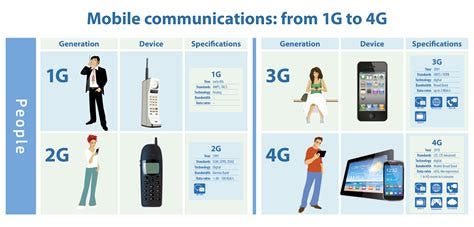

Alternative theories regarding the causes of respiratory illnesses have been proposed, including concerns about electromagnetic radiation from technologies such as cell phones, satellite phones, and wireless networks. These technologies, including the introduction of 2G, 3G, and 4G networks over the years, have raised questions about potential impacts on immune function.

Environmental factors such as cloud seeding with silver iodide, which has increased over the years, may have contributed to respiratory health issues.

Despite these claims, mainstream narratives assert respiratory illnesses to primarily stem from viral infections. Symptoms, including fever, cough, and difficulty breathing, often overlap across different respiratory illnesses, leading some to argue that they are merely rebranding of the same underlying conditions.

While alternative explanations such as the High-Frequency Active Auroral Research Program (HAARP) or solar activity, including sunspots and solar flares, have been suggested as potential contributors to respiratory ailments, scientific evidence supporting these claims remains limited.

The coincidence of respiratory outbreaks with the rise of various electric and related technologies, coupled with environmental changes such as increased cloud seeding, is intriguing and prompts questions about the true origins of these illnesses. It is peculiar that influenza, for instance, did not seem to exist prior to the rollout of these technologies and environmental interventions, which raises suspicions about their potential role in respiratory health.

And of course, there is the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which is claimed to be caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, is reported to have infected over 600 million people and resulted in more than 6 million deaths by early 2023, causing significant global disruption.

Numerous Germ Theory-based hypotheses about the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic have emerged. These include the idea that the virus originated from bats sold in a wet market in Wuhan, the possibility of snake venom being introduced into water systems, and the theory of a gain-of-function research accident at the Wuhan lab. Other mainstream scenarios suggest the virus could have leaked from a laboratory, crossed over from intermediate animal hosts, or resulted from a combination of natural and human-related factors.

The COVID-19 pandemic coincided with the global rollout of 5G technology, raising significant questions and skepticism about the official narrative. Major cities and regions where 5G was introduced include Wuhan (China), New York City (USA), Milan (Italy), and London (UK), all of which also experienced significant COVID-19 outbreaks. This timing has led to suspicions about a possible connection (which seems more plausible than any Germ Theory based assertion of etiology).

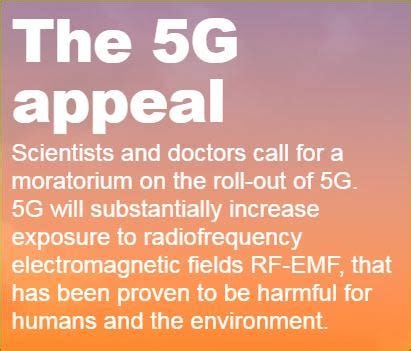

Before the rollout of 5G, a group of scientists and doctors signed a declaration called the 5G Appeal warning that 5G could be detrimental to human health in the EU. Despite these warnings, the rollout proceeded. People were diagnosed using PCR testing, which Kary Mullis, the inventor of the PCR technique, criticized for being inappropriate for diagnosing viral infections. Mullis, who died shortly before the pandemic, would likely have dismissed the use of PCR for COVID-19 diagnostics.

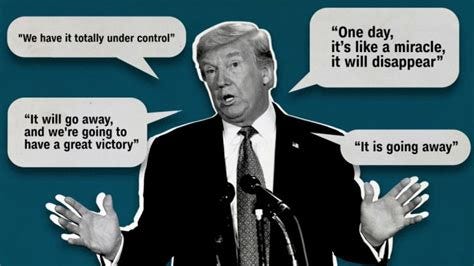

In 2019, a coalition of scientists, doctors, and advocates sent a National 5G Resolution letter to President Trump, demanding a moratorium on 5G until independent scientists could fully investigate its potential hazards to human health and the environment. This resolution, developed during the Electromagnetic Fields Conference in California, highlighted numerous studies showing harm from existing wireless technology and warned that 5G would increase exposure to untested technology. Despite these concerns, 5G was rolled out globally, with new antennas rapidly installed in front of homes and schools. The letter emphasized the need for precaution, especially for vulnerable populations like children and pregnant women, and called for urgent action to protect public health. Trump didn’t seem to care much and this technology was rolled out in the United States as well.

Following the rollout of 5G, individuals began experiencing respiratory symptoms resembling a severe influenza outbreak. Interestingly, cases of influenza appeared to non-existent with the emergence of this purportedly novel viral outbreak. The COVID-19 response included controversial and often fatal hospital protocols, such as the use of ventilators and medications to sedate patients on ventilators, which are thought to have contributed to patient deaths. Harmful medications used included Remdesivir, which has been linked to severe side effects. Additionally, the rapid development and emergency use authorization (EUA) of mRNA and other COVID-19 vaccines have raised concerns, with reports of injuries and deaths following vaccination.

Let's not address the alarming statistics of patients placed on ventilators in New York early on, where a significant percentage succumbed to the treatment. Nor should we discuss the financial incentives tied to utilizing these protocols, including Remdesivir. Don’t even think about how patients were given way too much Midazolam or Morphine that further suppressed their respiratory efforts that were already diminished.

The adverse effects and deaths resulting from forced vaccinations should be ignored as well. Instead, it's crucial to stay tuned to the media for updates on every new variant, from the Kraken variant to the Flirt variant, perpetuating fear and ensuring compliance with the mandates imposed by those in power. It's all purportedly for the greater good, despite the questionable methods and consequences.

Amidst the chaos, let's sprinkle in a dash of Monkey Pox, RSV, Bird Flu and a few other Germ Theory-based scares on the daily to ensure the panic remains well alive.

I reckon we're smack dab in the middle of yet another cosmic "CTRL+ALT+DEL" moment. Seems like it, doesn't it?

The parallels between all of the plagues, epidemics, and pandemics are pretty intriguing. Despite differences in symptoms, each scenario has led to significant societal changes, altering the course of history. How can one place any faith in the accuracy or transparency of these historical recorded events? I dare say that accounts of what happen daily in the media today don’t seem to be on track with either of those things, so can we really trust what we are told about what happened decades or even centuries ago?

One thing is for certain, it will be fascinating to observe the world's trajectory in the coming years following this contrived recent pandemic.

About two years ago, I came across an interview with Dr. Poornima Wagh, which felt like the culmination of a long search for information that aligned with my skepticism about conventional science. Despite my academic and professional background in the sciences and healthcare, the traditional teachings never quite resonated with me. Dr. Wagh provided compelling evidence suggesting that much of our scientific and historical knowledge is fundamentally flawed. Her revelations, however, came at a significant personal cost, as she faced relentless attacks from proponents of Germ Theory and the no-virus camp alike. The strong opposition she encountered suggests that there was substantial truth in her claims, unsettling to the established order. Regardless of her academic credentials, her insights resonated deeply with me, and I am profoundly grateful to her for unveiling a perspective beyond Germ Theory, freeing me from its constraints.

Exploring the debate between Germ Theory and Terrain Theory has been eye-opening, revealing the flaws of Germ Theory, which appears to be a tool of oppression and deception wielded by those in power for generations. This raises questions about whether any pandemics occurred naturally or if alternative explanations exist for the origins of illness…