In the late 1930s, a synthetic estrogen called Diethylstilbestrol (DES) was synthesized by British chemist Sir Charles Dodd.

Little did anyone know that this compound would become the center of one of the darkest chapters in pharmaceutical history.

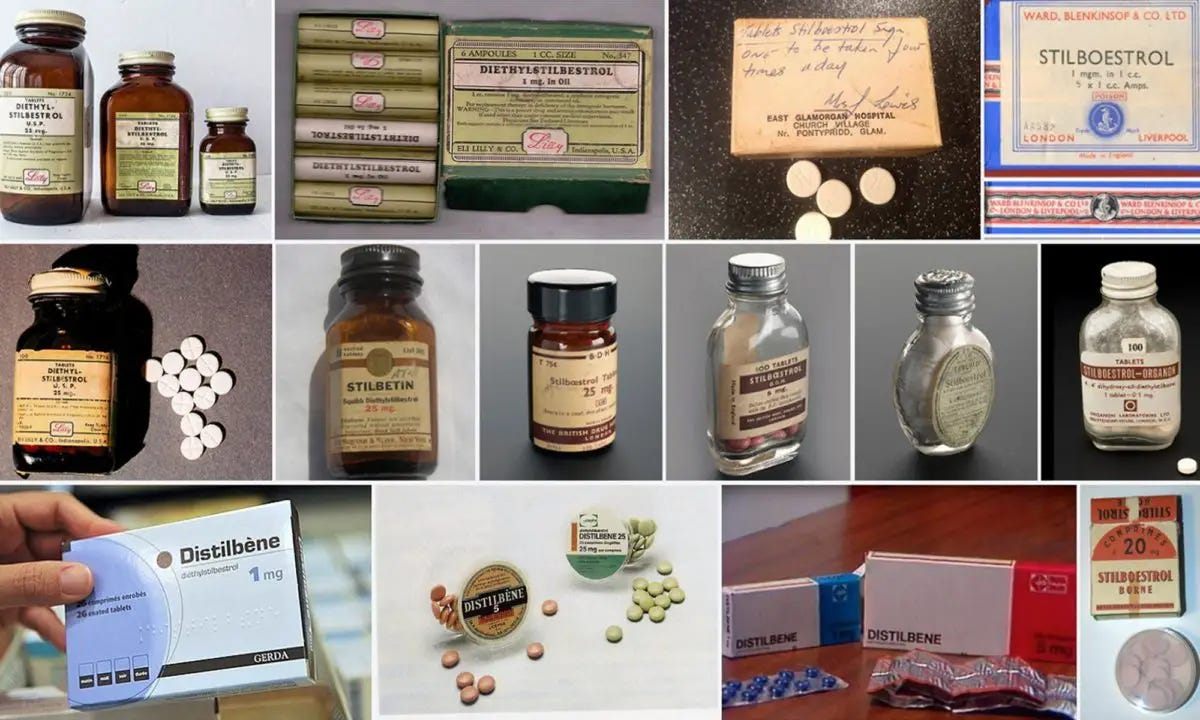

This nonsteroidal estrogen, believed to be five times more potent than estradiol, was inexpensive and easy to synthesize. Since it wasn't patented, the pharmaceutical industry rapidly started global production, leading to over two hundred brand names for various uses. DES received minimal toxicological testing, a situation typical for pharmaceutical products during that era.

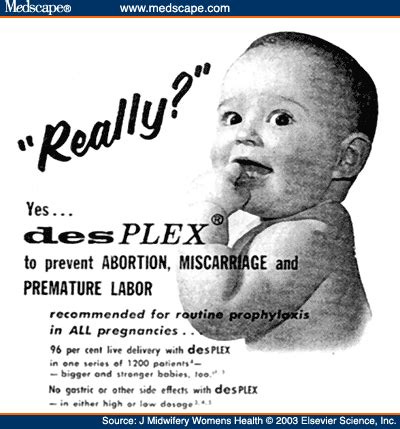

A few years later, experiments were conducted with high doses of DES in women at risk of miscarriage. The use of DES to prevent miscarriage gained popularity due to the work of Drs. Olive and George Smith, who conducted several uncontrolled trials of DES in pregnancy during the 1940s. Despite limited evidence of safety or effectiveness, the drug was considered effective for this purpose and deemed safe for both mother and fetus. In 1947, DES received market approval in the United States for use in pregnancy, particularly in cases of threatened abortion and hormonal inadequacy.

Merck, along with other manufacturers, eagerly marketed DES to doctors and pregnant women as a solution to pregnancy complications.

The widespread use of DES was facilitated by aggressive marketing and the lack of regulatory oversight. Despite concerns about its safety, DES was prescribed to millions of pregnant women for decades.

However, the true impact of DES wasn't fully understood until years later. It was discovered that DES exposure during pregnancy was linked to a range of devastating health issues:

Daughters of women who took DES faced an increased risk of clear cell adenocarcinoma, a rare vaginal cancer, as well as cervical cancer.

Both sons and daughters experienced reproductive tract abnormalities, infertility, and an elevated risk of certain cancers, including breast cancer.

Other adverse effects included increased risk of miscarriage, premature birth, and developmental abnormalities in offspring.

In 1953, W.J. Dieckmann and colleagues conducted a randomized trial comparing DES to a placebo in pregnant women, demonstrating its lack of efficacy. Despite this finding, DES continued to be prescribed, even to women without prior pregnancy issues or signs of threatened pregnancy. A reanalysis of Dieckmann's data in 1978 revealed that DES actually increased the risk of miscarriage and stillborn deaths. Had the data been properly analyzed in 1953, nearly twenty years of unnecessary DES exposure could have been prevented.

Despite mounting evidence of these dangers, DES remained on the market until the early 1970s when it was finally pulled following revelations of its harmful effects.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) played a role in this, although their regulatory actions were delayed and inadequate, allowing DES to be prescribed for far too long.

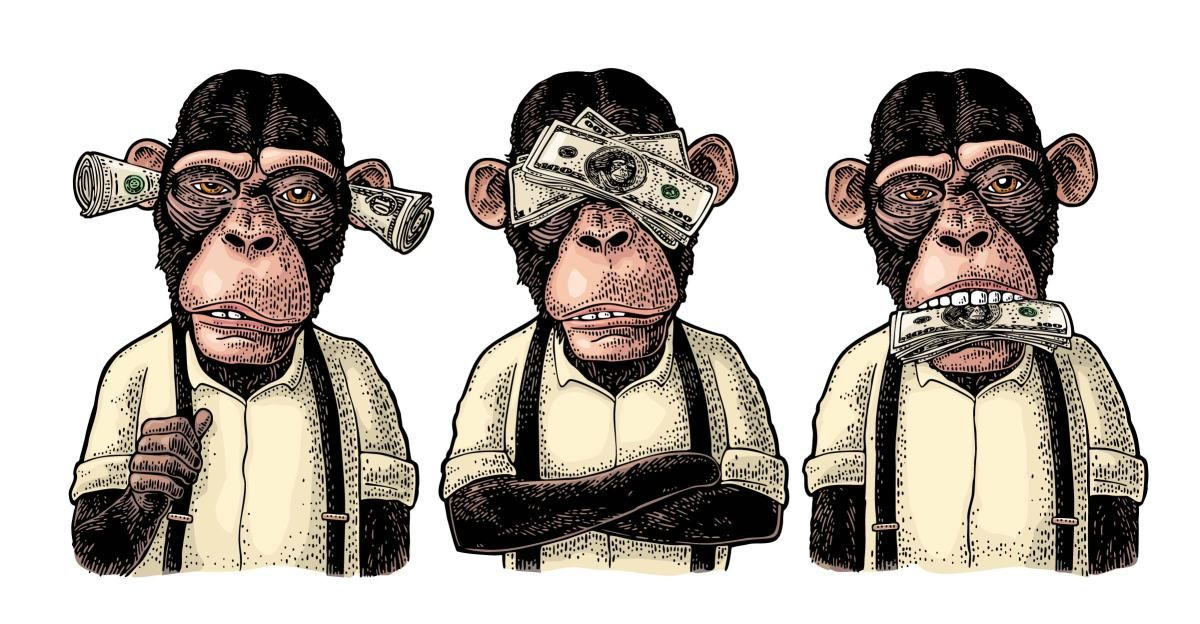

Merck & Co., Inc., as one of the leading manufacturers of DES, seems to bear a significant responsibility for the harm caused. In 1974, Merck and 28 other drug manufacturers and distributors faced a $35 million lawsuit over DES. The 16 initial plaintiffs argued that they developed vaginal cancer and other health problems because their mothers had used DES. The lawsuit also contended that DES was made from Stilbene, a known carcinogen, and criticized the lack of valid evidence supporting its effectiveness. A year before the lawsuit, the FDA had banned DES hormones for use in cattle due to cancer-causing residues found in some animals' livers, but the ban was overturned after no public hearings were held. Following the plaintiffs' actions, the court mandated that the defendants inform other potential victims and set up early detection and treatment centers. This led to over 350 plaintiffs seeking damages totaling around $350 billion.

However, the story doesn't end there. In recent years, Merck has developed medications aimed at purportedly preventing or treating disorders that may actually be potential side effects from DES exposure without anyone putting two and two together. While these medications are not explicitly blamed on the DES tragedy, one may question if they are related. The medications include:

Gardasil: Merck's HPV vaccine is used to prevent cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancers supposedly caused by certain strains of the human papillomavirus (HPV). But is it really?

Keytruda: Merck's immunotherapy drug is used to treat various cancers, including cervical cancer. While primarily known for its use in various other cancers, Keytruda has shown promise in certain cases of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Keytruda may be used in combination with chemotherapy for TNBC that expresses PD-L1.

Lynparza (olaparib): Lynparza, co-developed by AstraZeneca and Merck, is a PARP inhibitor used in the treatment of HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer with a BRCA mutation. It is typically used in patients who have received prior chemotherapy.

Merck's involvement in both distributing and marketing products that potentially causes and treat cancers and other disorders raises significant ethical concerns. This creates a major conflict of interest, where the same company profits from both helping to cause the problem and providing the solution to the problem.

Screening for DES exposure and illness includes discussing the mother's pregnancy history, looking for physical signs associated with DES exposure, and recommending regular Pap smears and pelvic exams for women to screen for cervical cancer, which has been linked to DES exposure. Additional tests such as colposcopy, ultrasound, or biopsy may be recommended based on individual risk factors.

Screening for Diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure typically involves a review of medical history and physical examination. Since DES was prescribed to pregnant women primarily between the 1940s and 1970s, individuals born during this time or those whose mothers may have taken DES during pregnancy are at risk. However, many offspring may not even realize they have been exposed to the drug by their grandmothers or mothers, potentially leading to undetected health impacts. Therefore, consultation with healthcare providers is crucial for personalized risk assessment and appropriate screening recommendations to detect any potential health issues early.

While the direct impact on grandchildren is less studied, there is evidence suggesting that DES exposure may have transgenerational effects, meaning it could impact the health of subsequent generations. Therefore, the grandchildren of women who took DES may be at increased risk of certain health conditions, although the extent of this risk and the specific mechanisms involved are still being investigated.

The investigation into the transgenerational effects of DES exposure involves various researchers, healthcare professionals, and organizations.

Medical Researchers: Scientists and medical researchers around the world are studying the long-term effects of DES exposure on subsequent generations. This research often involves epidemiological studies, laboratory experiments, and analysis of health records to understand the potential risks and mechanisms involved.

Healthcare Providers: Healthcare providers, including gynecologists, oncologists, and primary care physicians, play a crucial role in identifying and monitoring individuals who may have been exposed to DES and their offspring. They contribute to ongoing research by documenting cases, providing clinical insights, and recommending appropriate screening and management.

Government Agencies: Government health agencies, such as the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), support research initiatives and provide guidance on DES-related health issues. They are also supposed to collect data and disseminate information to healthcare professionals and the public, but this does not seem to be an issue readily made available to the public. I have never heard of this issue until today.

Patient Advocacy Groups: Organizations dedicated to supporting individuals affected by DES exposure, such as the DES Action USA, advocate for research funding, raise awareness about DES-related health risks, and provide resources and support for affected individuals and their families.

Academic Institutions: Universities and research institutions conduct studies on DES and its potential impacts on subsequent generations. These institutions contribute to the scientific understanding of DES-related health issues through their research activities and collaborations.

The adequacy of the investigation into the impact of Diethylstilbestrol DES is a pressing concern that warrants greater attention.

Recent inquiries among individuals I've encountered revealed a concerning lack of awareness about DES and its harmful effects.

Reflecting on my own family history, I am left to ponder whether my maternal grandmother, who experienced multiple miscarriages in the late 1940s and 1950s, was prescribed DES. Could this drug have influenced the health outcomes of subsequent generations in my family? The incidence of breast cancer in my aunt, despite her otherwise healthy lifestyle, and my mother's history of miscarriages and reproductive complications, including my premature birth due to her abnormally shaped uterus, raise further questions. My own health struggles, including the need for surgery to remove a teratoma on my ovary, prompt me to consider the possibility of DES exposure unknowingly affecting my own reproductive health.

These reflections underscore the urgency for continued investigation into the long-term effects of DES and the need for greater awareness and understanding of its potential impacts on individuals and families.

The tragic legacy of DES serves as a stark reminder of the need for rigorous testing, transparency, and ethical considerations in pharmaceutical development and marketing. It highlights the importance of robust regulation and the duty of companies like Merck to prioritize patient safety above all else.

As we continue to unravel the story of DES, we must not forget the countless lives that have been impacted by this pharmaceutical catastrophe. It's a story of negligence, resilience, and the ongoing quest for justice and accountability in the world of medicine.

DES daughter here.

DES daughter, and I had cancer in my late 20's -- my girlfriend who lived across the street from me all during our school years, died from Ovarian Cancer when she was 30 y/o. She also was a DES daughter.

Thanks for this article!