Germ Theory, which asserts that microorganisms are the primary cause of many diseases, has long been questioned by skeptics who argue that it oversimplifies disease causation.

This skepticism extends to the testing methods used to detect viral infections and spike proteins, which are perceived by some as fundamentally flawed and non-specific. But who funded these studies, who created these tests, and how are they utilized in justifying modern medical practices?

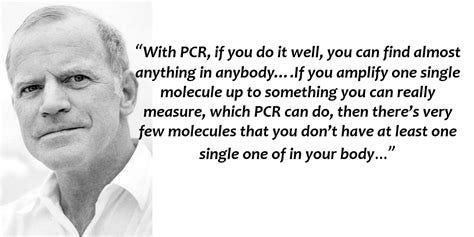

PCR, or Polymerase Chain Reaction, was invented by Kary Mullis in 1983 while working for Cetus Corporation, a biotechnology company that funded much of his initial research. Cetus Corporation, based in Emeryville, California, played a significant role in the development and commercialization of PCR technology.

The company later sold the PCR patents to Hoffman-La Roche, a major Swiss multinational healthcare company, in 1991 for $300 million, indicating the significant commercial and scientific interest in this diagnostic tool.

PCR technology has also received funding and support from various governmental bodies, including the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Department of Defense has shown interest in PCR for its potential applications in detecting biological warfare agents.

The PCR test is utilized to detect and amplify specific genetic sequences purportedly present in biological samples, often targeting DNA or RNA from organisms like viruses or bacteria. Its application is widely promoted in medical diagnostics and research for identifying pathogens and genetic markers associated with diseases, despite ongoing debates and skepticism surrounding its reliability and interpretation in certain contexts. Despite its widespread use, critics argue that PCR is highly prone to producing false positives due to its sensitivity in amplifying even trace amounts of genetic material, which may not indicate an active infection or clinically relevant presence.

ELISA, or Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay, was developed by Peter Perlmann and Eva Engvall in the early 1970s while they were at the University of Stockholm in Sweden, initially commissioned by the Swedish company Pharmacia for the purpose of detecting and quantifying proteins, particularly antibodies, in biological samples.

Initial research for ELISA was supported by academic institutions and public health grants. The commercial development of ELISA kits was later funded by biotech companies such as Abbott Laboratories and Ortho Clinical Diagnostics. These companies were instrumental in bringing ELISA to the market, making it a standard tool in laboratories worldwide. The widespread use of ELISA in disease surveillance and research has been supported by various health organizations, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay) test has been historically used for diagnosing infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, and Lyme disease, as well as monitoring autoimmune disorders and allergies by detecting specific antibodies or antigens in biological samples. Today, it remains widely utilized in clinical laboratories for medical diagnostics due to its sensitivity and specificity. ELISA assays are employed for screening blood donations, monitoring viral load in HIV patients, detecting autoimmune antibodies in diseases like lupus, and assessing allergic responses via allergen-specific IgE antibody measurement. Additionally, ELISA tests play a crucial role in research settings for biomarker studies, drug development, and various scientific investigations requiring accurate protein or antibody quantification. However, ELISA is often criticized for its lack of specificity, with cross-reactivity potentially leading to false positives and false negatives, calling into question its reliability.

Western blotting was first described by W. Neal Burnette in 1981 while he was working at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington. Burnette's research was primarily supported by academic institutions and government research grants, including those from the NIH.

Western blotting technology has been widely adopted by both academic and commercial laboratories, with companies such as Bio-Rad Laboratories and Thermo Fisher Scientific producing reagents and equipment for the technique. The method's semi-quantitative nature and subjective interpretation can introduce variability and error, fueling skepticism about its accuracy and reliability.

Lateral flow assay (LFA) technology, developed by companies like Unipath Ltd. (a Unilever subsidiary) and later by Alere Inc. (now part of Abbott Laboratories), operates on capillary action and antibody-antigen interactions. In LFAs, a liquid sample moves across a strip containing reagents that react with specific target molecules, producing a visible signal used in tests like home pregnancy and COVID-19 antigen detection.

Despite their widespread use, LFAs are often criticized for their inherent limitations. These include variability in sample application, environmental conditions affecting test performance, and the potential for false-positive or false-negative results due to cross-reactivity or inadequate sensitivity. Critics argue that LFAs, while convenient for quick assessments, may lack the precision needed for critical diagnostic decisions. Efforts continue to refine LFA technology, improve reagent reliability, and address these concerns to enhance their diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility.

These testing methods often produce misleading results due to their limitations. PCR's sensitivity, while a strength, can also be a flaw. The ability to amplify trace amounts of DNA or RNA can lead to false positives, particularly if the viral material detected is not from an active infection. ELISA and Western blotting can suffer from cross-reactivity, where non-specific antibodies react with the target, leading to false positives. The subjective nature of interpreting Western blot results further complicates their reliability. Lateral flow assays, known for their rapid results, are less reliable in detecting low levels of viral proteins, which can lead to false negatives. Their ease of use does not always equate to accuracy, as they can also show false positives due to cross-reactivity.

Many doctors may lack a comprehensive understanding of the intricacies and limitations of diagnostic testing across various technologies. The varying levels of familiarity among healthcare providers with different diagnostic methodologies could potentially lead to inconsistent reliance on test results, affecting the accuracy of patient diagnoses and the efficacy of treatment decisions.

The utility of these tests in guiding medical practice is immense, but so are the implications of their limitations. Misuse and inherent flaws of these methods emphasize the need for critical reevaluation and continuous improvement in diagnostic technologies. Understanding who funded and created these testing methods, and how they are utilized, sheds light on the complex interplay between scientific innovation and its practical applications. While these tests are widely used in modern medicine, their limitations must be acknowledged and addressed. Enhanced transparency in their development and use, coupled with ongoing innovation, is essential to ensure diagnostic practices that truly benefit public health are both accurate and reliable.

All the diagnostic test listed above are pattented crap where results can be manipulated. Amplified or De-amplified....ask anf Lyme Disease patient. Western Blot test is one of those tests.

Best testing is microscope. However that is not allowed since 2000 .......and has been eliminated from most Veterinarian practices as well.

Hi Betty, actually Mullis didn't do much but have an acting career:

https://protonmagic.substack.com/p/mullis-the-movie-star