Once Rare, Now Ubiquitous: The Rise of Food Allergies

Not long ago, peanut butter sandwiches were a staple of childhood. Classrooms had bake sales, Halloween was a candy free-for-all, and latex gloves were a non-issue in medical offices, and kids could have latex gloves at birthday parties.

Today, the landscape has changed dramatically. Peanut allergies, once virtually unheard of, now affect an estimated 2.5% of children in the United States.

Latex allergies, once a rarity, have surged, impacting up to 6% of the general population and as much as 17% of healthcare workers. What happened?

A growing body of research suggests that the overuse of antibiotics may play a pivotal role in this dramatic shift, disrupting our microbiomes and reshaping our immune systems in ways we are only beginning to understand.

The Allergy Explosion: By the Numbers

To appreciate the scale of this modern epidemic, consider these statistics:

Food Allergies: In the U.S., food allergies affect approximately 32 million people, including 1 in 13 children (roughly two per classroom). Peanut allergies alone have tripled in prevalence between 1997 and 2008.

Latex Allergies: Estimates suggest latex allergies now affect 1%-6% of the general population and up to 17% of healthcare workers, a significant rise since latex gloves became commonplace in the 1980s.

Latex allergies, particularly in children, have become an increasing concern in schools and public spaces, with latex balloons being a common trigger for severe allergic reactions. Studies estimate that 3-5% of children with atopic conditions may be sensitized to latex, prompting many schools to ban latex balloons during parties and events to ensure student safety.

This move toward creating "latex-safe environments" also includes eliminating other latex-containing items, such as certain bandages and rubber bands, to protect children with sensitivities and reduce the risk of life-threatening reactions. These measures, however, were not as common 30 years ago; a sudden concern for latex allergies began growing in the 1990s and early 2000s, becoming a more prominent safety focus in schools by the 2010s.

Antibiotic Usage: The average American child receives three courses of antibiotics by age two, and nearly 30% of all antibiotic prescriptions are deemed unnecessary .

Populations thrived for centuries before the advent of antibiotics, raising the question: are they truly essential, or have we been conditioned to believe they are a cornerstone of health?

As the widespread use of antibiotics increasingly correlates with a surge in chronic health issues, perhaps it’s time to reconsider whether their role in modern medicine is as indispensable as we've been led to think. Could the reliance on antibiotics be more about perception than necessity?

Antibiotics and the Microbiome: A Tale of Collateral Damage

Antibiotics have been heavily marketed as essential, but they are not without consequence. These powerful drugs don’t discriminate between harmful microbes and beneficial bacteria, often decimating the delicate ecosystem of the gut microbiome. This disruption has far-reaching implications for immune system development and function.

The gut microbiome serves as a training ground for the immune system, teaching it to differentiate between harmful invaders and harmless substances like food proteins. When antibiotics alter the composition of the microbiome, this education process can go awry. The result? An immune system prone to overreacting to benign substances, such as peanuts or latex proteins.

The Link Between Antibiotics and Food Allergies: What You Need to Know

Research increasingly suggests a connection between antibiotic use and the development of food allergies (there are tons of scholarly articles on this I just picked one), including shellfish and other common allergens. Antibiotics disrupt the delicate balance of the gut microbiome, a critical regulator of the immune system, potentially leading to immune dysregulation and allergic sensitization (as well as a many many other health issues).

Studies show that infants exposed to antibiotics early in life are significantly more likely to develop food allergies later, with specific sensitivities to shellfish, peanuts, eggs, and dairy being observed. This rise in food allergies aligns with the widespread use of antibiotics over recent decades, raising questions about their long-term impact on health. While environmental factors can also play a role, the disruption of gut bacteria by antibiotics appears to be a key factor driving this alarming trend.

A Personal Story: A Life Changed by a Cookie

Take the story of “Sarah”, a mother whose son, “Jake”, experienced an anaphylactic reaction at a birthday party after eating a peanut butter cookie.

“Sarah” was baffled. No one in their family had food allergies, and “Jake” had eaten peanut butter as a toddler without issue. What changed?

“Sarah” recalled that “Jake” had multiple ear infections as a baby, each treated with antibiotics. At the time, she hadn’t connected the dots. Now, she wonders if those early courses of antibiotics disrupted his microbiome, setting the stage for his life-threatening allergy. (Yes…this really happened).

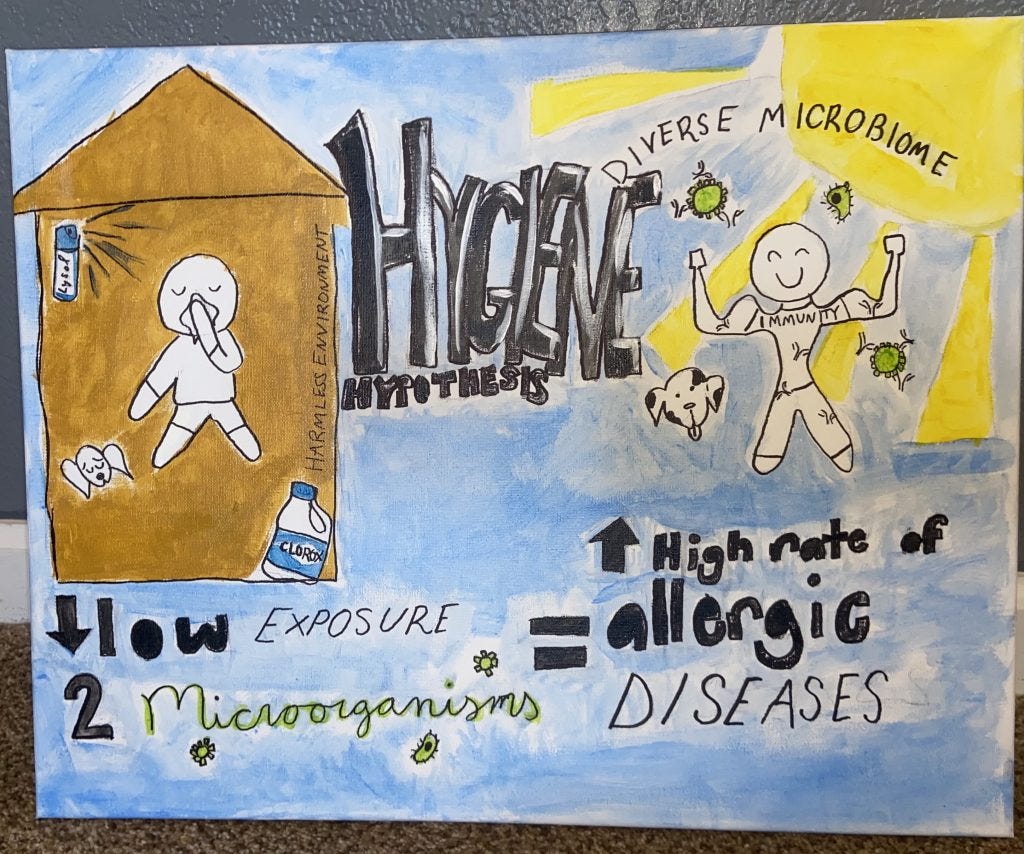

The Hygiene Hypothesis Meets Antibiotics

The rise of allergies aligns with the “hygiene hypothesis,” which posits that reduced microbial exposure in early life leads to immune dysregulation. Antibiotics amplify this effect, wiping out beneficial bacteria that might otherwise help calibrate the immune system.

For example, Bacteroides fragilis, a key gut bacterium, is known to produce molecules that regulate immune responses. When antibiotics deplete such bacteria, the immune system may become hyper-reactive, mistaking harmless proteins for dangerous invaders and overreact.

Historical Context: Allergies Were Once Rare

Before the widespread use of antibiotics, food allergies were practically nonexistent. The term "allergy" itself was coined in 1906 by Clemens von Pirquet, marking the early 20th century as the period when allergic reactions began to be formally recognized.

In 1906, Clemens von Pirquet observed that patients who had received horse serum or smallpox vaccines previously had more severe reactions to subsequent injections. He coined the term "allergy" to describe this hypersensitivity reaction. This led him to hypothesize that tuberculin, isolated by Robert Koch in 1890, might cause a similar reaction. Charles Mantoux expanded on Pirquet's work, creating the Mantoux test, which became a diagnostic tool for tuberculosis in 1907. (After this work he supposedly and very suspiciously died by suicide in early 1929, but that’s another Substack altogether).

Notably, the first documented cases of peanut allergies appeared in medical literature during this time. However, it wasn't until the late 20th century, particularly around the 1990s, that a significant increase in peanut allergies was observed. This surge coincides with the period when antibiotic use became more widespread, leading researchers to investigate potential links between early antibiotic exposure and the development of food allergies.

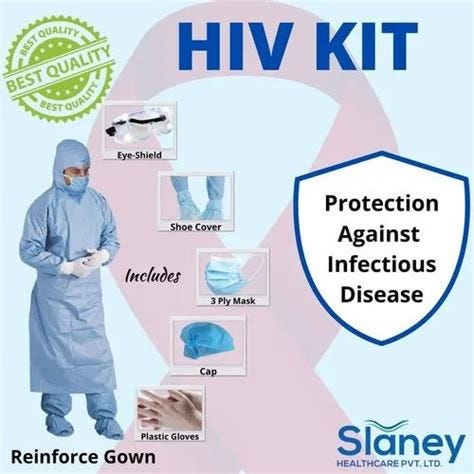

Latex allergies were virtually unheard of until the late 1980s, coinciding with the widespread adoption of latex gloves in medical settings. This surge in allergic reactions is attributed to increased exposure to latex proteins, particularly among healthcare workers. The introduction of universal precautions during the supposed HIV/AIDS epidemic led to a significant rise in latex glove use, which, in turn, heightened sensitization to latex proteins.

The rise in allergies during the COVID-19 pandemic may be closely tied to disruptions in the gut microbiome, which plays a vital role in regulating the immune system, as well as increased exposure to allergenic materials like latex. Increased antibiotic use during the pandemic likely disrupted the balance of gut bacteria, impairing immune tolerance and making individuals more prone to allergic reactions. Overuse of hand sanitizers and disinfecting wipes may have further reduced exposure to beneficial environmental microbes, which are crucial for maintaining a diverse and healthy microbiome. Prolonged mask-wearing and hyper-cleanliness practices also limited microbial exposure and may have contributed to gut dysbiosis.

Additionally, the widespread use of PPE, such as latex-containing gloves and goggles, increased exposure to latex proteins, leading to higher rates of sensitization and allergic reactions, particularly among healthcare workers and those frequently using these materials. Reduced social interaction and time outdoors during lockdowns compounded these effects, particularly in children, whose gut microbiomes are still developing. Combined with heightened stress, which negatively affects gut health, these factors likely fueled the marked increase in allergies and immune-related conditions during this time.

While the direct connection between microbiome disruption and latex allergies is still under investigation, it's well-established that a balanced microbiome is crucial for immune regulation. Disruptions in the gut microbiota can lead to immune dysregulation, potentially increasing the risk of various allergic diseases.

Today, even simple joys like handing out latex balloons at birthday parties or special events are fraught with risk. Many children cannot participate due to the prevalence of severe latex allergies, a stark reminder of how profoundly these allergies have reshaped everyday life.

Antibiotics, Allergies, and the EpiPen Controversy

As food allergies have risen, so has the reliance on emergency treatments like EpiPens. These devices, which deliver life-saving epinephrine to counteract severe allergic reactions, have become a necessity for many families. However, the cost of EpiPens has skyrocketed in recent years.

In 2007, a two-pack of EpiPens cost around $100. By 2016, the price had surged to over $600, sparking public outrage and congressional investigations. Critics argue that the monopoly on the device, combined with the increasing prevalence of severe allergies (exacerbated by gut microbiome disruption), has created a perfect storm of financial and medical burden for families.

Statistics Tell the Story

A 2018 study published in JAMA Pediatrics found that infants treated with antibiotics within the first six months of life were at an increased risk of developing allergic diseases, including food allergies.

Additionally, research indicates that children exposed to multiple courses of antibiotics have a higher likelihood of developing allergies compared to those who had not. These findings suggest a significant association between early antibiotic exposure and the subsequent development of allergic conditions due to the direct impact on the gut microbiome.

Moving Forward: What Can Be Done?

The good news is that awareness is growing, and steps can be taken to mitigate the risks:

Judicious Antibiotic Use: Avoid unnecessary antibiotics, particularly in early childhood.

Probiotics: Supplementing with probiotics during and after antibiotic treatment may help restore gut balance.

Diverse Diets: A varied diet rich in fiber supports a healthy microbiome, which can help “train” and strengthen the “immune system”.

Exposure Therapy: For some food allergies, controlled exposure therapy shows promise in retraining the immune system under the supervision of a professional trained to do this.

The Bigger Picture

While antibiotics are often presented as essential tools, their overuse has had unintended consequences, including the rise of allergies. Some argue that this trend is exacerbated by the pharmaceutical industry’s focus on creating lifetime customers rather than addressing root causes.

By understanding and addressing these links, we can take steps to reverse the trend and protect future generations. Opting for natural antibiotics, such as garlic, ginger, and oregano oil, can be a safer alternative for both children and adults, especially when addressing mild infections. For infants under one year old, honey should be avoided, but breast milk offers natural immunity, while other remedies like garlic and turmeric can support the immune system in older children. These natural options help avoid disrupting the gut microbiome and contribute to overall health, though it's important to consult a healthcare professional for appropriate guidance and dosing.

The next time you see a peanut-free zone or hear of a latex allergy, consider the hidden role antibiotics may have played in reshaping our immune systems—and our world.

Thank you for mentioning about natural alternatives to antibiotics: ginger, oregano oil, garlic, and raw honey. I'd also consider chaparral, chlorine dioxide, colloidal silver, and urine therapy.