The relationship between the gut microbiome and chronic pain has emerged as one of the most fascinating and promising areas of health research. The gut microbiome, a collection of trillions of bacteria and other microorganisms residing in our digestive tract, does far more than aid in digestion. It plays a critical role in regulating the immune system, mental health, and even pain perception. However, while exploring the connection between gut health and chronic pain, it is crucial to tread carefully, especially when considering extreme interventions like fecal microbiota transplants (FMT). Let's break it all down.

The Gut-Pain Connection

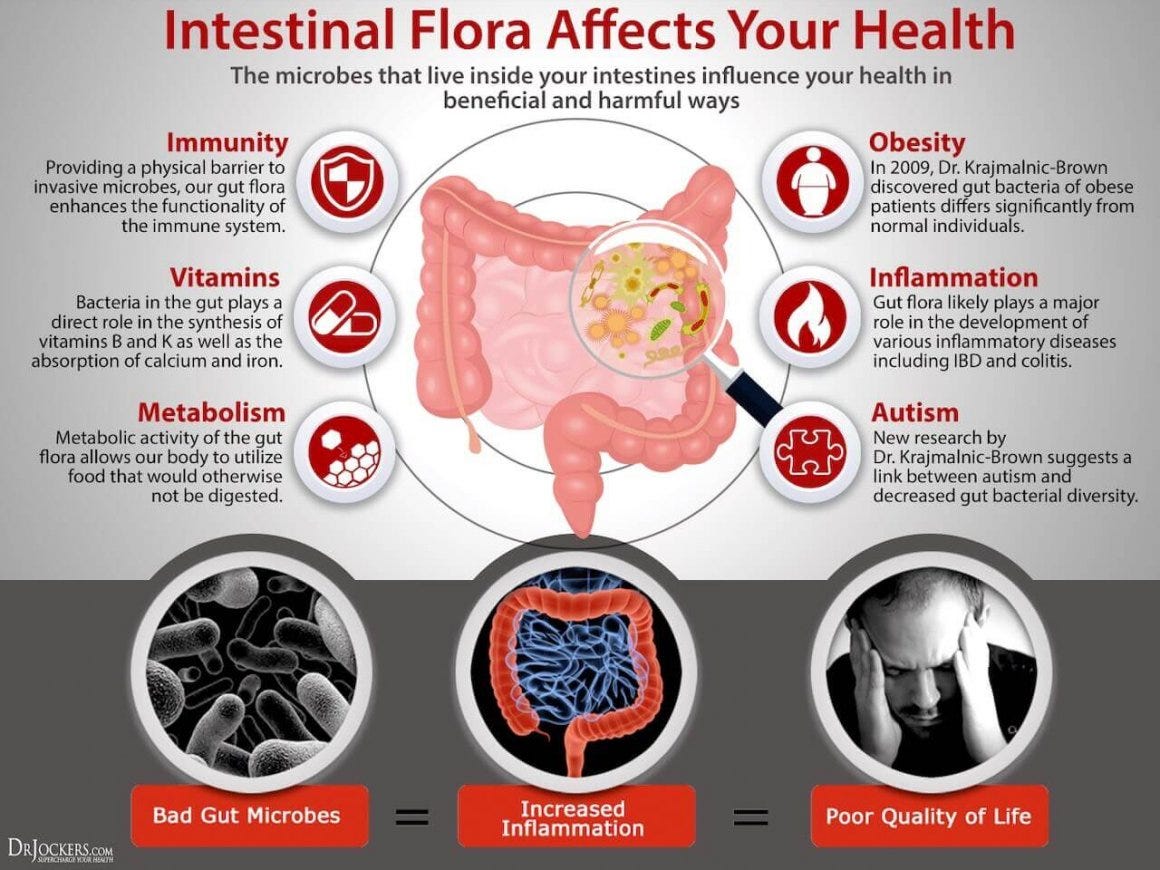

Chronic pain conditions—from fibromyalgia and arthritis to neuropathy and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)—often share a common thread: inflammation.

A healthy gut microbiome can help manage inflammation, while an imbalanced microbiome (a condition known as dysbiosis) can exacerbate it.

Here’s how:

Inflammation and Immune Response: Dysbiosis increases gut permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut.” This allows inflammatory molecules like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to escape into the bloodstream, triggering widespread inflammation and potentially worsening chronic pain.

Neurotransmitters and Pain Perception: Gut bacteria produce critical neurotransmitters, including serotonin and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which influence how the brain perceives pain. An unhealthy gut can disrupt this balance, amplifying pain signals.

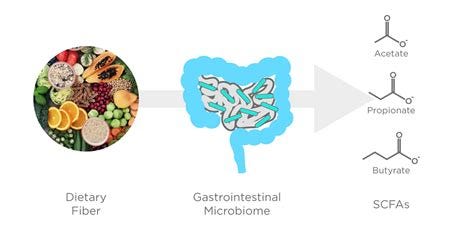

Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs): Beneficial gut bacteria produce SCFAs, which have anti-inflammatory properties. These compounds can reduce pain by calming the immune system and promoting healthy nerve function.

Gut-Brain Axis: The gut and brain communicate directly through the vagus nerve, meaning gut health directly impacts mental health—a significant factor in chronic pain conditions, which are often accompanied by anxiety and depression.

Supporting Gut Health for Pain Relief

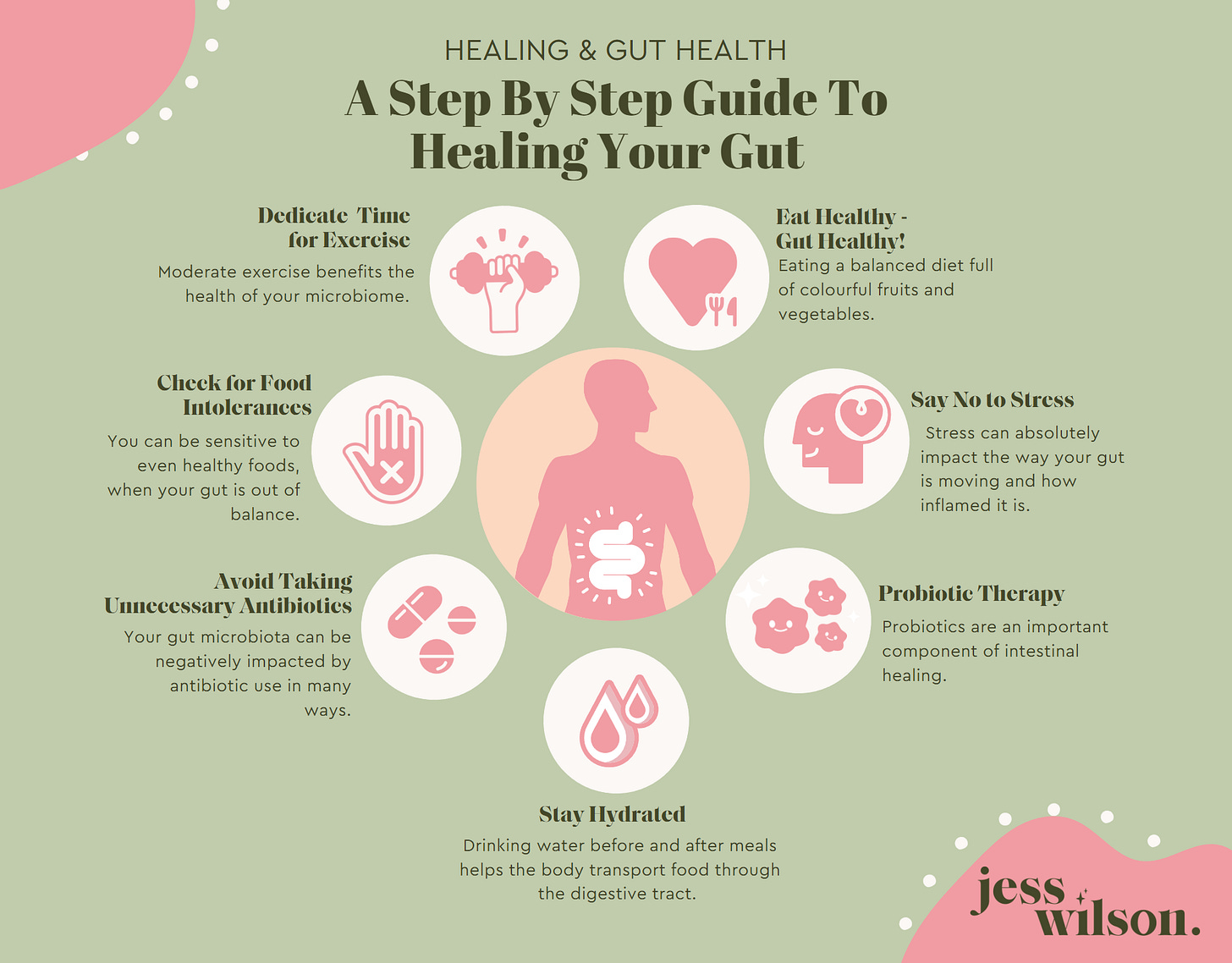

Given the gut’s influence on pain, supporting a healthy microbiome is a logical step for managing chronic pain.

Here are evidence-based approaches:

Dietary Changes:

Fiber-Rich Foods: High-fiber diets (including vegetables, fruits, legumes, and whole grains) nourish beneficial gut bacteria, promoting SCFA production.

Anti-Inflammatory Foods: Incorporate omega-3 fatty acids (found in fatty fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts) and polyphenols (found in berries, green tea, and olive oil).

Limit Processed Foods and Sugars: These can fuel harmful bacteria and worsen dysbiosis.

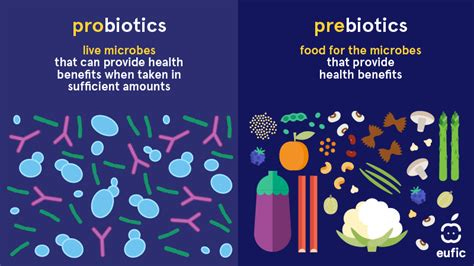

Probiotics and Prebiotics:

Probiotics, especially strains like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, can help restore balance to the microbiome.

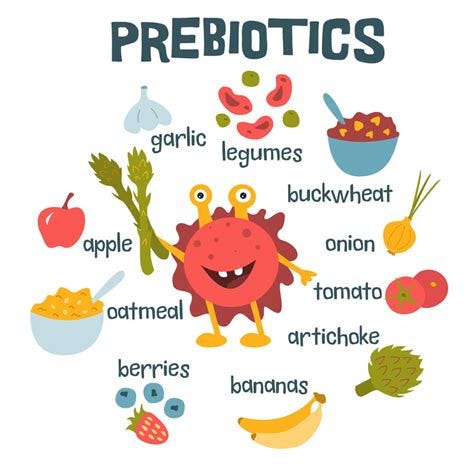

Prebiotics (found in foods like garlic, onions, and bananas) feed beneficial bacteria.

Avoid Pharmaceuticals that Promote Dysbiosis:

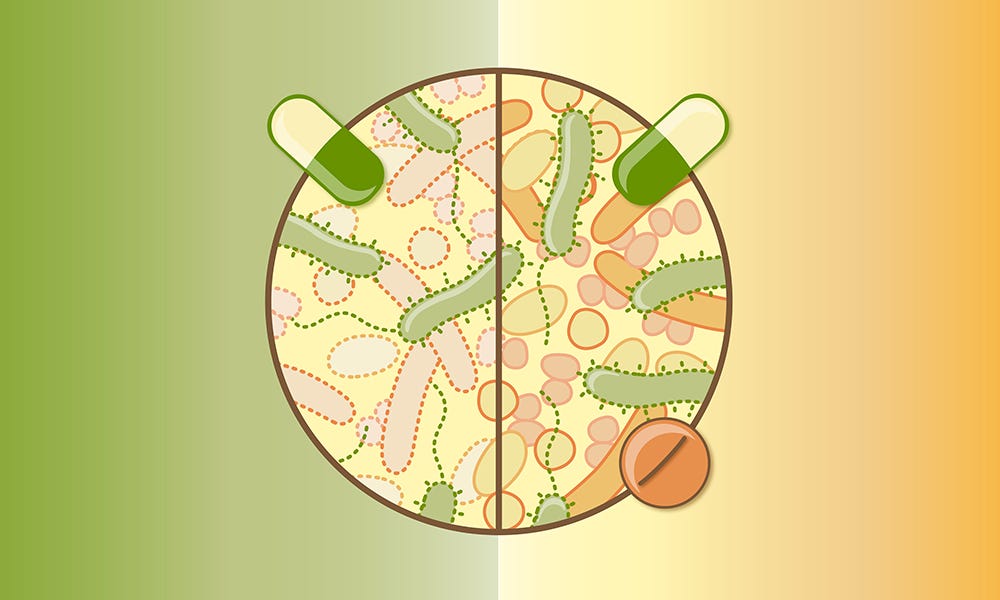

Antibiotics: While sometimes necessary, antibiotics can disrupt the microbiome by killing both harmful and beneficial bacteria. Overuse should be avoided whenever possible (if used at all).

Pain Medications: Certain pain medications, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), can damage the gut lining and worsen dysbiosis. Opioids have also been linked to microbial imbalances and increased gut permeability.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs): Often prescribed for acid reflux, PPIs can alter the composition of the gut microbiome and promote dysbiosis.

Stress Management:

Chronic stress disrupts the gut-brain axis and worsens gut health. Practices like mindfulness, yoga, and deep breathing can help.

Physical Activity:

Exercise supports both gut and overall health, reducing inflammation and improving pain tolerance.

Beware of Fecal Microbiota Transplants (FMT)

In the rush to improve gut health, some have turned to fecal microbiota transplants (FMT) as a potential quick fix. FMT involves transferring stool from a healthy donor to the gut of a patient, aiming to reset the microbiome. While this procedure has shown promise in treating certain conditions like recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections, it is far from a universal or risk-free solution.

The Risks of FMT

Disrupting Your Microbial Balance: Implanting someone else’s microbes into your gut can introduce strains that may not harmonize with your existing microbiome. Each individual’s microbiome is unique, and what works for one person may disrupt another’s natural balance.

Infection: Even with rigorous donor screening, there is a risk of introducing harmful pathogens. Cases have been reported where patients developed severe infections or sepsis following FMT.

Unpredictable Outcomes: The microbiome is incredibly complex, and scientists are still learning how specific strains of bacteria interact. Introducing a new microbiome can have unintended consequences, potentially worsening existing health conditions.

Immune Reactions: The introduction of foreign bacteria can trigger unexpected immune responses, especially in individuals with autoimmune conditions or compromised immune systems.

Ethical and Regulatory Concerns: FMT is still an experimental procedure for most conditions, and its long-term effects are not well understood. Many practitioners offering it operate in a regulatory gray area, leaving patients vulnerable to substandard care.

Proceed with Caution

While the gut microbiome holds great promise for managing chronic pain, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Extreme interventions like FMT should be approached with caution, if not avoided entirely. Instead, focusing on safe and “sustainable” lifestyle changes can often yield significant benefits without the risks.

The connection between gut health and chronic pain emphasizes the importance of taking a holistic approach to wellness. By nourishing the microbiome through diet, probiotics, stress management, and exercise, and by avoiding unnecessary pharmaceuticals, you can support your body’s natural pain relief mechanisms while avoiding unnecessary and potentially harmful procedures.