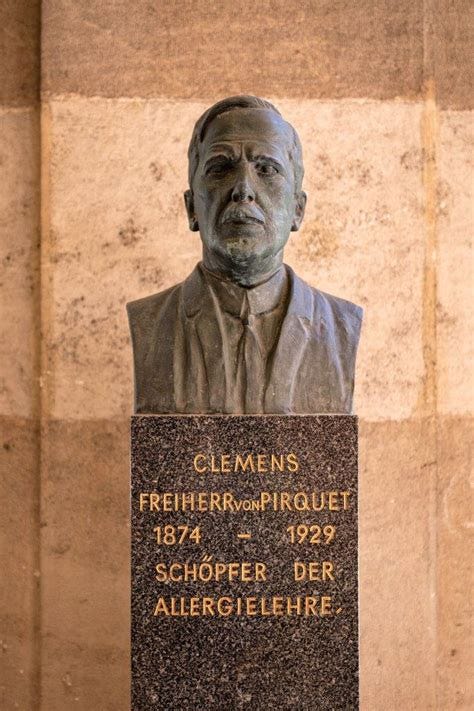

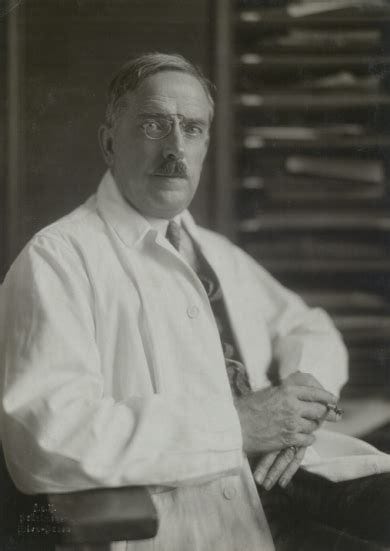

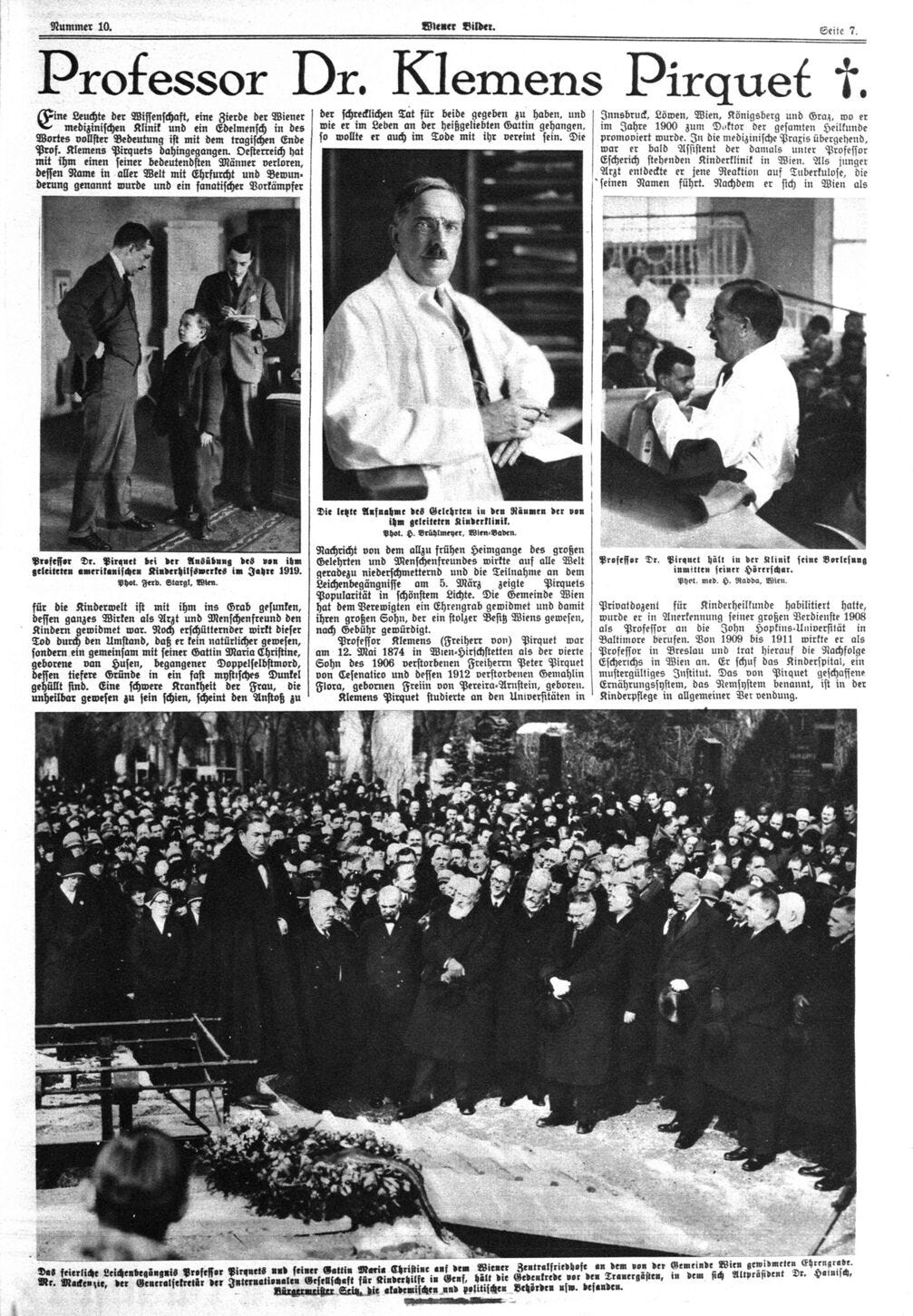

Clemens Peter Freiherr von Pirquet

A Pioneer Silenced by Germ Theory Fraud & Modern Medicine's Growing Empire... or Something far More Sinister?

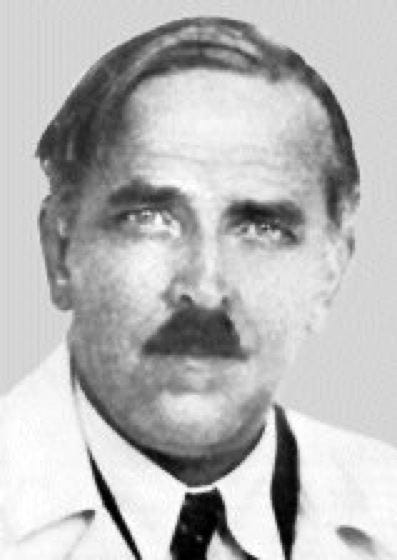

Clemens Peter Freiherr von Pirquet, commonly known as just Clemens von Pirquet, (1874–1929) was a revolutionary figure in early 20th-century medicine. His discoveries fundamentally reshaped immunology, nutrition, public health, and pediatrics, and introducing concepts like serum sickness and opened the field of allergy and latent tuberculosis while exposing flaws in treatments such as antitoxin serum therapy.

His career saw him rise to the pinnacle of academic medicine, holding prestigious positions at Johns Hopkins University for a short period of time and the University of Vienna. Yet his life ended suddenly and mysteriously in 1929, when he and his wife were found dead in their Vienna apartment, the deaths were officially ruled as double suicide by potassium cyanide poisoning (which is very VERY sus).

Von Pirquet’s relentless pursuit of truth put him at odds with powerful institutions, including the Pasteur Institute, the Rockefeller Foundation, the pharmaceutical industry, and influential figures such as Paul Ehrlich. His discoveries exposed serious flaws in widely celebrated medical treatments, threatening entrenched interests. Was von Pirquet silenced for challenging the foundations of early 20th-century medicine? Or was his death, as officially claimed, the result of personal struggles? The story of Clemens von Pirquet is one of brilliance, controversy, and mystery, offering a lens into the tensions between science, power, and profit.

Early Life: A Restless Pursuit of Knowledge

Born on May 12, 1874, in Hirschstetten near Vienna, Austria, Clemens von Pirquet came from a noble Austrian family. Clemens von Pirquet was the son of the Imperial Council and State Parliament member Peter Baron Pirquet of Cesenatico, known as de Mardaga (1838–1906), and of Flora, née Baroness von Pereira-Arnstein (1845–1912), who came from a Jewish Viennese banking family.

Clemens von Pirquet’s academic path reflected a restless curiosity. He began his studies in theology at the University of Innsbruck as a Jesuit priest, later switching to philosophy at the University of Leuven, before ultimately finding his calling in medicine. In 1900, he graduated from the University of Graz with an M.D., beginning a career that would redefine the medical sciences.

Under the mentorship of Theodor Escherich, Pirquet honed his skills at Vienna's Universitäts Kinderklinic. Escherich’s influence helped propel von Pirquet into the emerging field of immunology, where his observations of immune responses to foreign substances would change the course of medical history.

Rise to Prominence: Allergy, Tuberculosis, and Antitoxin Therapy

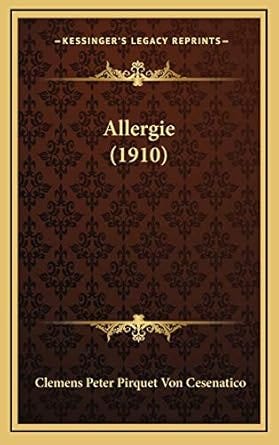

One of Pirquet’s most significant contributions occurred between 1903 and 1910, during which he redefined how the immune system and infectious diseases were understood. His groundbreaking work introduced new concepts to immunology and revealed the dangers of treatments celebrated as breakthroughs.

Allergy and Serum Sickness

In 1906, von Pirquet coined the term "allergy", derived from the Greek words allos (other) and ergon (reaction), to describe the immune system’s hypersensitivity to foreign substances.

His discovery stemmed from his observations of serum sickness, a reaction caused by injecting patients with antitoxin serums—animal-derived antibodies used to combat diseases like diphtheria and tetanus. It is has been over 100 years since Clemens von Pirquet wrote his classic paper introducing the term ‘allergy’. Although the word is no longer used in the way he intended, his concept of ‘changed reactivity’ laid the foundation for the modern science of immunology.

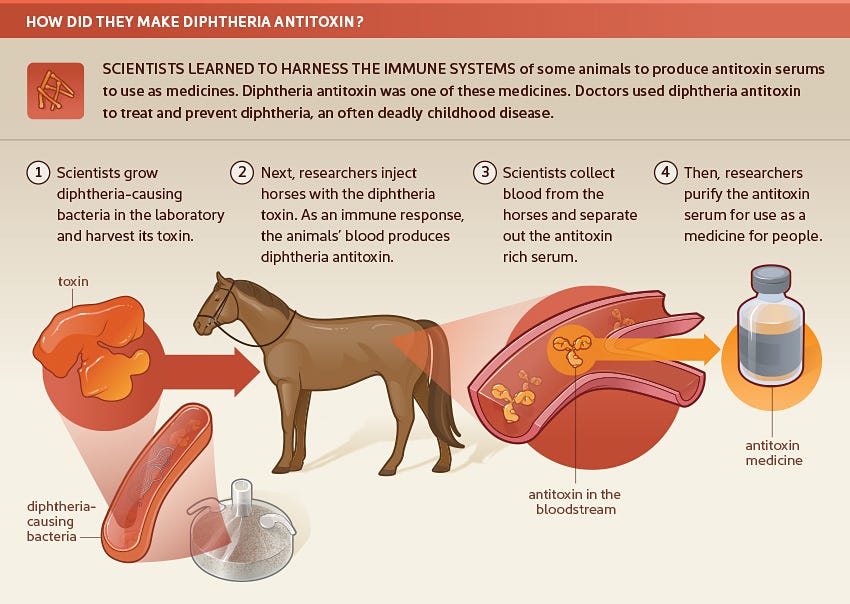

Developed by Emil von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato, antitoxin therapy was hailed as a medical triumph.

However, von Pirquet and his student Béla Schick revealed its darker side:

Severe Reactions: Patients often developed rashes, joint pain, and fevers due to their immune systems reacting violently to the foreign proteins in the serum (vaccinal allergy also known as serum sickness).

Lack of Purity: Early antitoxin production methods were crude, leading to contamination and inconsistent potency.

Ethical Concerns: The risks of serum sickness were often downplayed by institutions heavily invested in promoting antitoxins.

As with many miracles, however, antitoxin came with a hitch: serum sickness. In some patients, injections of antitoxin resulted in an immune reaction characterized by fever, rash, swelling of the glands, and joint pain. In 1905, Austrian pediatricians Clemens E. von Pirquet and Béla Schick published the results of their investigation into this phenomenon, in their treatise Serum Sickness (in the original German, Die Serumkrankheit.)

Their research demonstrated that patients who were repeatedly injected with serum suffered not only more intense bouts of sickness with each successive injection, but in some cases, antitoxin injections resulted in dangerous anaphylaxis. What patients were experiencing was in fact an allergic reaction to horse proteins present in the antitoxin serum. (Von Pirquet and Schick coined the word “allergy” in 1906.)

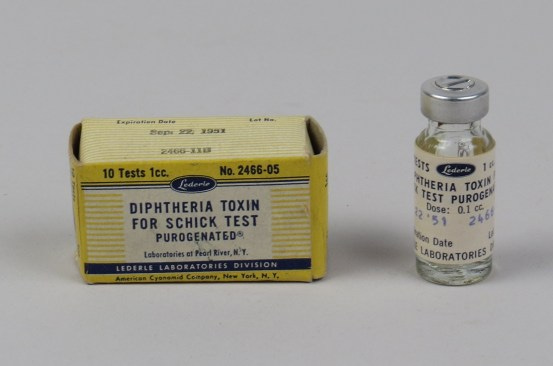

So now doctors were faced with a conundrum: how to balance the risks of serum sickness with the benefits of controlling diphtheria outbreaks through preventative antitoxin injections? Enter the Schick test. In the early 1910s, Schick developed a simple skin test that allowed doctors to distinguish between those with a natural immunity to diphtheria from previous exposure and those who stood to gain protective temporary immunity from an injection.

Doctors injected a very small dose of diphtheria toxin in a salt solution (1/50 of the minimal lethal dose for a guinea pig) into the arm of a patient to be tested. As a control, the other arm was injected with the same amount of toxin in a salt solution, mixed with enough antitoxin to neutralize its effect. Within 24-48 hours, those patients who had never been exposed to diphtheria showed a redness at the injection site of the toxin as the body mounted an immune response to the novel substance. This “positive” Schick test identified which patients would benefit from a dose of preventative antitoxin serum.

The test proved useful not only in preventing unnecessary exposure to serum, but in developing a greater understanding of the epidemiology of diphtheria. Schick tests on large groups of people provided data indicating that the time of greatest susceptibility to diphtheria was between the ages of one and four. This window encompassed a period when infants had lost the immunity provided to them from their mothers but before children had enough exposure to non-virulent strains to develop their own immunity.

In 1923, Schick moved to the US, after accepting a post at New York’s Mount Sinai Hospital. Just two years prior to his arrival, his test provided the New York Public Health System with an important tool in their mass diphtheria immunization campaign for the city’s school children. The Schick test determined which students were not yet immune and should receive a dose of a new vaccine which conferred immunity for years rather than the mere three weeks of the earlier antitoxin serum. Students participating in the drive were given buttons reading “I am Schicked! Are you?”

In 1957, with diphtheria under control in the United States, an 80 year old, still-practicing Schick was featured in Life magazine. Despite his lengthy pediatric career, Schick remained best known for his test, prompting him to tell the reporter documenting his day-to-day work “You see, I’m not just a scratch on the arm!”

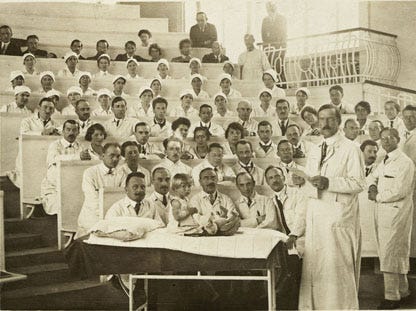

Pirquet and Schick. Image from https://circulatingnow.nlm.nih.gov/2014/02/25/bela-schick-and-serum-sickness/

Von Pirquet’s findings highlighted how treatments meant to save lives could also cause harm. Especially when people were injected with subsequent doses of these substances.

These revelations disrupted the dominant narrative around antitoxin therapy, drawing scrutiny to powerful institutions like the Pasteur Institute, which was deeply involved in its production and promotion. (I don’t subscribe to all the germ theory ideas presented in this video, but the historical context and coincidences are fascinating).

However, his uncompromising stance and refusal to align with powerful institutions likely made him enemies. In 1909, von Pirquet declined an offer to join the Pasteur Institute (whose work was funded by a rich Jewish banking heiress), a decision that may have further isolated him from the medical establishment. The Pasteur Institute, a dominant force in vaccine and antitoxin research, had significant financial and reputational stakes in promoting these therapies. Pirquet’s critiques of antitoxins threatened their position and profit, placing him in direct conflict with one of the most influential medical institutions of the time.

Cécile Furtado-Heine

Cécile Furtado-Heine is often celebrated as a philanthropist, but beneath her charitable façade lies a more complex and potentially troubling narrative. Born into immense wealth and connected to powerful networks, Cécile may not have wielded her fortune not merely fo…

The Dark Side of Antitoxin Therapy

Antitoxin serum therapy, though revolutionary in its time, was far from perfect:

Severe Immune Reactions: Von Pirquet’s identification of serum sickness revealed how the therapy could harm patients, undermining its reputation as a universal solution.

Profit-Driven Medicine: Institutions like the Pasteur Institute heavily promoted antitoxins, despite their flaws, as they were a lucrative product of the growing pharmaceutical industry.

Scientific Rivalries: Figures like Paul Ehrlich, who worked to standardize antitoxins, were closely tied to the success of these therapies. Von Pirquet’s findings, which exposed their risks, may have created professional tensions.

Von Pirquet’s critiques of these treatments disrupted a medical system increasingly driven by profit, possibly placing him at odds with influential individuals and organizations.

The Rift Between Clemens von Pirquet and Paul Ehrlich

Clemens von Pirquet openly criticized Paul Ehrlich, a prominent German physician and scientist often referred to as the "father of immunology" and "father of chemotherapy." Ehrlich’s groundbreaking work included the development of techniques to standardize antitoxin therapy, which involved using animal-derived serums to neutralize bacterial toxins like those from diphtheria and tetanus. He also introduced methods to measure the potency of antitoxins and was instrumental in advancing early immunotherapy.

However, von Pirquet disagreed with Ehrlich’s reductionist approach, arguing that it oversimplified the complexities of immune responses and ignored the risks associated with treatments like serum sickness, a harmful immune reaction caused by the foreign proteins in antitoxin serums. Von Pirquet’s research demonstrated that these celebrated therapies could harm patients, a critique that challenged Ehrlich’s work and the institutions, such as the Pasteur Institute, that heavily promoted antitoxins. Their professional discord reflected a broader divide in early immunology, with von Pirquet emphasizing the need to understand immune hypersensitivity and long-term risks, while Ehrlich focused on standardization and widespread implementation of these treatments. There is detailed information about Ehrlich in the article below:

From Cancer to COVID

BioNTech's pandemic narrative is often spun as a "miracle" of science, one that rocketed forward under the fittingly titled "Project Lightspeed," a name that ironically matches their high-stakes race to market. Wit…

The Tuberculin Skin Test and Latent Tuberculosis

Clemens von Pirquet’s research extended beyond antitoxins to the study of immune responses, particularly through his work on smallpox vaccination. He observed that subsequent exposures to the vaccine triggered heightened immune reactions, an insight that laid the foundation for his later work with tuberculin. Tuberculin, a substance first isolated by Robert Koch in 1890, became central to von Pirquet’s efforts to understand and combat tuberculosis (TB), one of the deadliest diseases of his time. In 1907, he developed the tuberculin skin test, known as the Pirquet reaction, which could detect prior infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. This test revealed that many infected individuals were asymptomatic yet at risk of developing active disease, introducing the concept of latent tuberculosis. By shifting the focus from treating visible symptoms to early detection and prevention, von Pirquet’s work transformed public health approaches to TB.

Von Pirquet also studied the critical role of nutrition in the progression and prevention of TB (aligning more with Terrain Theory over the dominating Germ Theory of that time). He demonstrated that malnourished children were more likely to develop active TB and that proper nutrition could aid in both prevention and recovery.

These findings highlighted the connection between socioeconomic factors and disease outcomes, emphasizing the importance of addressing underlying health conditions. Beyond diagnostics, von Pirquet used his tuberculin test to differentiate between latent and active infections, fundamentally altering how TB was understood and managed. Despite his groundbreaking contributions, he declined an invitation to join the Pasteur Institute, but it is unclear why. His innovations in tuberculosis research, including his work that later inspired the Mantoux test, remain a cornerstone of modern medicine. Despite being nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in recognition of his achievements, he never received the award.

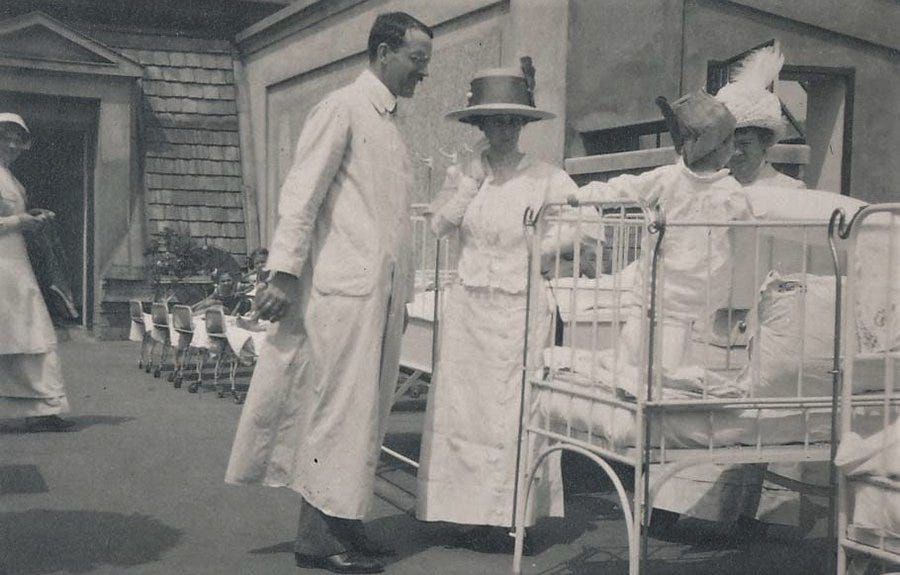

Professional Success and Conflicts with Power

Von Pirquet’s career saw him rise to international prominence. In 1909, he became the first Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at Johns Hopkins University. There, he played a key role in planning the Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children, one of the first pediatric clinical facilities in the United States. However, von Pirquet left after just one year (some reports state two years), declining offers to extend his tenure. He left Johns Hopkins before the Harriet Lane Home was completed and never returned. His decision to return to Europe points to someone determined to uphold his values, even when prestigious opportunities were on the table. While the official story cites financial reasons, that doesn’t quite add up given his family’s wealth. So, what really happened? We may never know.

In 1911, von Pirquet succeeded Theodor Escherich as Professor and Chair of Pediatrics at the University of Vienna. This was the most prestigious pediatric positions in Europe, and he held it until his death in 1929. During this time, von Pirquet continued his work dealing with serum sickness, allergies, and immunology while also focusing on the social, nutritional, and public health aspects of pediatrics.

As head of the University Children’s Clinic in Vienna, Clemens von Pirquet set new standards in nutrition, hygiene, and the training of nurses and pediatricians. He prioritized school hygiene, medical services, and dentistry, delivering public lectures to raise awareness about disease prevention. In 1924, he introduced a dental chart numbering system that was later adopted by the World Health Organization in 1970.

Pirquet also broke new ground in child neuropsychiatry, using creative therapeutic activities such as reading, singing, and storytelling to engage his young patients. His clinic was the first in the world to focus on the clinical research and treatment of brain damage and behavioral disorders in children. To improve collaboration between doctors and nurses, he implemented a requirement for future physicians at his clinic to complete a nursing internship, fostering a stronger partnership between medical teams.

Clemens von Pirquet: A Visionary of Nutritional Medicine in a World of Competing Agendas

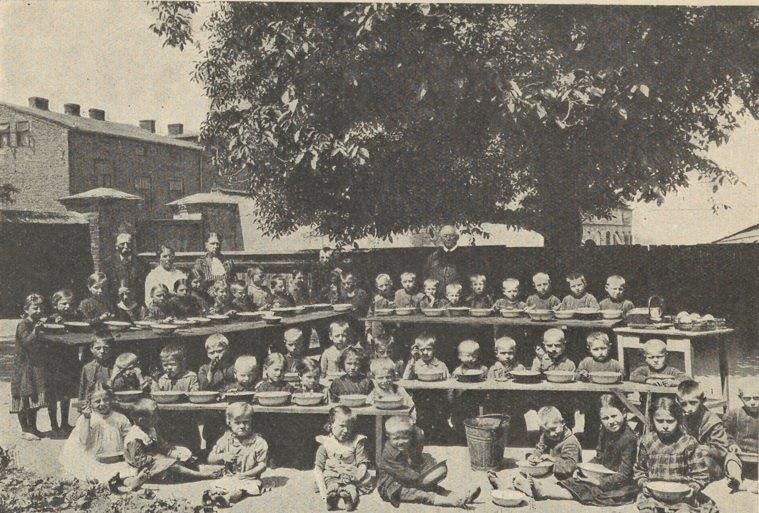

Clemens von Pirquet, a pioneering Viennese pediatrician, played a vital role in public health initiatives during the turbulent reconstruction of Central Europe between 1918-the 1920s following the Great War. Vienna, once the thriving center of the Habsburg Empire, was left devastated by economic collapse, famine, and disease (which amazingly made way for the League of Nations, which is the United Nations today, remarkably seems to have made little progress in resolving the same issues we continue to face today).

As the city struggled with broken supply networks, failing state finances, and malnourished populations (due to food chain supplies being cut off on purpose aka these institutions created the problems so they could provide the solution and gain power), Pirquet’s innovative approach to health care—focused on nutrition as a cornerstone of recovery—stood in stark contrast to the prevailing strategies of powerful global health organizations. Pirquet developed the nutrition system NEM (Nähreinheit Milch, or Milk Nutritional Unit, where 1 NEM equals 1 gram of milk) for malnourished children.

After World War I, this system formed the basis of a large-scale children’s feeding program, known as the “American Relief Action for Children,” which he organized throughout Austria between 1919 and 1921. He was also elected chairman of the League of Nations Committee on Infant Welfare.His efforts, particularly in collaboration with the American Relief Administration (ARA), headed by U.S. Food Administrator Herbert Hoover, were crucial in addressing the dire needs of postwar Austria (which much like today these institutions seem to create the problems to provide their solutions which gains them unlimited power).

But can any of these people or organizations truly be trusted? What was really in the food these global public-private institutions were distributing? Could the supplies have been deliberately tainted to cause illness? Given their poor track record, it wouldn’t be shocking if they intentionally triggered mass sickness during this time much like we have seen over the past few decades.

But not to digress….Pirquet’s success was tied to his extensive connections with American physicians, philanthropists, and advisors. Herbert Hoover’s ARA relied on experts like Pirquet to provide the local knowledge and infrastructure necessary for relief programs, such as feeding malnourished children in Vienna. Pirquet also interacted with influential figures within the Rockefeller Foundation and the League of Nations Health Organization, such as Ludwig Rajchman, who helped coordinate international health efforts in postwar Europe.

Yet, while Pirquet’s collaborations highlighted the importance of trust and expertise in these relief programs, his focus on nutrition as a primary tool for combating disease diverged sharply from the priorities of institutions like the Rockefeller Foundation, the Pasteur Institute, and Johns Hopkins University.

These organizations were deeply invested in advancing vaccines, serum therapies, and laboratory-based medical solutions, often overshadowing systemic approaches like improved nutrition and public health infrastructure.

Sara Silverstein’s chapter on “Reinventing International Health in East Central Europe” presents an intriguing argument about the role of public health in state building efforts of the successor states, the relevance of networks, institutions, and norms inherited from the Habsburg monarchy, and the League of Nations as an institutional and intellectual hub. If we read her fine chapter together with the one by Katja Naumann, we can better understand the structuring from the Habsburg past, the coordination work done by the League, and the key role played by the Rockefeller Foundation with its funding strategies, which benefitted successor states like Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, and Yugoslavia directly and the entire region through the support of the League of Nations Health Organization.[12]

The Great War brought about a radical shift in global markets, international relations, and hegemonic powers. America grew into the dominant creditor and New York became the most powerful financial market. America was a key point of reference in the public finance crisis of the immediate postwar years. Austria is again a good case in point. The imminent collapse of its public finances, closely related to hyperinflation and a flight of capital from the country, prompted the government to seek rescue from the British and American financial markets. Public finance rescue missions in the interwar period were a complex challenge, where a new figuration of public and private actors became involved.[13] At a time when the Harding administration wanted to bypass European affairs as much as possible, American capital and, in the case of the Hungarian bailout, American experts were already involved.

The public finance rescue efforts provide an excellent starting point for a concluding reflection on the position of America in the remaking of Central Europe. The Allied military organization was built on multilateral coordination of production, transportation, and deployment. This experience was used by experts like Jean Monnet within the framework of the League, and by the American technical advisor Col. Causey within the Austrian government. The practice of embedding experts and their expertise in new institutional settings was used by the Rockefeller foundation as much as by Allied governments. This practice had a strong potential to support state building in the successor states, as the public health sector proves,[14] and the building of international collaboration within the framework of the League of Nations. American expertise remained sidelined in the latter effort, when the Harding administration stepped forcefully on the breaks of multilateral engagement. This was a pity for many reasons. It prevented American project management, which was for many Europeans characterized by “efficiency, energy, and innovativeness,” as Frank Costigliola argues,[15] from shaping the newly crafted procedures of the League of Nations. At the same time, being kept away from the League and its cumbersome committee work meant that American experts were not socialized into the opportunities and limits of multilateral program development and implementation.

Pirquet’s unique position also invites speculation about the pressures and conflicts he may have faced. His mother’s ties to a prominent Jewish banking family likely facilitated his access to elite networks in Europe and America, but his emphasis on practical, localized health solutions may have clashed with the broader agendas of the institutions he worked alongside. These organizations, aligned with industrial and pharmaceutical interests, sought to expand their influence through top-down public health strategies, often prioritizing technological advancements over addressing basic needs like “food security”. The ARA, led by Hoover in Europe, has an unsettling resemblance to what was happening in the United States with children supposedly being "saved" through public-private “philanthropic” initiatives like the Orphan Trains.

Unmasking the Odd Fellows

The 1800s remain one of the most puzzling centuries in history, full of odd events and inexplicable phenomena that continue to baffle historians (and me connecting the dots with these secret societies and hisorical going ons).

Even today, these efforts are glorified, but it seems like these public-private institutions created the starvation in these areas only to swoop in with their medicines and food to appear as saviors. What happened to all the children, and where were their parents? The entire situation feels deeply unsettling.

There’s something deeply suspicious about this period in history, particularly regarding the treatment of children.

The Suspicious History of TB Wards and Child Separation

In Clemens von Pirquet’s time, tuberculosis (TB) was labeled a devastating threat, and children diagnosed with it were often forcibly separated from their families and sent to TB wards, called preventoriums or sanatoriums/sanitariums, for extended periods.

Von Pirquet’s own research suggested that proper nutrition and fresh air could prevent or treat TB, yet thousands of children were institutionalized, sometimes for years. Many never returned, as high mortality rates in these facilities supposedly kept families from ever reuniting. Estimates suggest that countless children were sent to these wards, only for parents to be told their children had died, often without proof.

This pattern, alongside other contemporaneous efforts like orphan trains, that operated between 1854 and 1929, raises serious questions about the true intent behind these separations. Was TB used as a justification to separate children from their families? Did von Pirquet’s research into TB’s preventability uncover something troubling about these institutions, and could this have contributed to the circumstances surrounding his untimely death?

France Paved the Preventorium Path

For millennia, physicians believed that heredity or a weak constitution caused TB. In the 1880s, German scientist Robert Koch revealed that the disease was caused by a contagious bacterium invisible to the naked eye. This knowledge did not, however, speed the quest for a cure. Treatment remained what it had long been: fresh air, heliotherapy (sunlight), a carefully titrated exercise-to-rest ratio, increased rations of food, health monitoring by nurses and doctors, and education to avoid spreading the disease to others.

Efforts to fight tuberculosis represent America’s first modern public health campaign. Sick people who could afford to travel to the mountains, desert, or seaside, depending on what their particular doctor recommended, did so. Physicians and nurses forcibly relocated indigent sufferers, if they refused to go voluntarily, to newly created institutions such as Mont Alto. States and cities enacted laws to prohibit dangerous practices such as spitting, and private organizations such as the National Tuberculosis Association sponsored research, supported dispensaries (free clinics for the poor), and spearheaded other initiatives.

But They Look Fine…

The children at Mont Alto stayed at the part of the institution known as the “preventorium.” The idea for such a place emerged in the wake of Austrian pediatrician Clemens von Pirquet’s 1907 research.

Using an orphan in his Vienna clinic, Pirquet demonstrated that tuberculin, a byproduct of the tubercle bacillus culture, was important to diagnosing TB infection. When injected just under the skin, those individuals who had been exposed to tuberculosis developed a reddened, warm-to-the-touch, hard bump at the injection site within 48 hours. Pirquet’s finding revolutionized the American anti-tuberculosis movement. Public health experts had long known that a large percentage of deaths from tuberculosis occurred in young adults. But almost 75 percent of seemingly healthy children who received Pirquet’s tuberculin test proved to be infected with the bacillus. Since not everyone who became infected developed full-blown TB, public health reformers reasoned that other factors influenced progression from infection to disease.

Before Pirquet’s research, clinicians classified children into two groups with regard to TB: the sick and the well. After 1908, a third disease category was created, pretuberculosis. Pretubercular children were infected with the organism, but did not have active disease.

A Disease of the Poor

In addition to their positive tuberculin test, what most of Mont Alto’s children had in common with one another was that they were indigent. By the early twentieth century, public health reforms such as pure milk, better quality food, and less crowded living circumstances had reduced TB deaths among the middle and upper classes. Morbidity and mortality had always been more prevalent among the poor, but now simple infection became increasingly associated with poverty and unfortunate personal hygiene and health habits.

The numbers of poor Americans swelled in the early twentieth century. As the pace of industrialization accelerated, many moved to urban areas seeking greater economic opportunity. In addition, waves of immigrants, many of them low-income, poured into U.S. cities. Crowded into tenements, their living conditions created a perfect incubator for TB. Public health leaders feared the epidemic would spiral out of control. In the absence of a cure for TB, reform-oriented nurses, doctors, scientists, and philanthropists decided that the best way to prevent the disease becoming symptomatic was to provide state-of-the-art sanatorium care soon after infection. Since Pirquet’s test showed that most people were infected early in life, this meant targeting children.

The campaign to institutionalize poor children suspected to be at high risk for developing TB expanded after World War I. A media barrage in the professional literature and the lay press helped popularize the movement. By the early 1920s dozens, perhaps hundreds, of such institutions operated throughout the United States. Some operated as private, voluntary institutions, while others were founded with private funds but managed by public agencies such as public health departments or school districts. Still others functioned in conjunction with public or private hospitals or sanatoria. All preventoria in the South were segregated, and there were no beds for African-American children, although these youngsters experienced high rates of TB morbidity and mortality correlated with poverty. As is visible in the film footage, Mont Alto accepted African-American children, though they were few in number. Records show black and white children lived together at the institution’s preventorium, but Mont Alto’s adult wards were segregated by race. The National Tuberculosis Association’s 1923 nationwide directory of all TB-related institutions explicitly makes this point about Mont Alto’s adult wards.

Child-Saving

The preventorium idea embodied the leading edge of not just one popular reform movement, but two: tuberculosis prevention and “child-saving.” Children represented a powerful unifying force during this era; those who disagreed with one another on debates roiling the country—such as whether or not massive rates of immigration were altering America’s national character, and if so, whether the change was for better or worse—could almost always agree that children were “innocent” and, as such, deserved an investment in their health and social welfare. And relative to adults, fundraising for children’s ventures was easy and popular.

The youngsters arriving by train at Mont Alto most likely hailed from Philadelphia or Pittsburgh. They came to the attention of nurses and doctors at a dispensary when a parent or another adult living in the home sought treatment for TB-related symptoms. In order to receive care, all children with whom they lived were tested. Those children who reacted to tuberculin boarded the train for a preventorium if a bed was available. Care for children at the preventorium was free, just as it was for adults at the sanatorium. While some children are quite thin, they look healthy by contemporary standards, probably because they felt well. Moreover, they act like we expect children to behave. They playfully jockey with one another and seem to be having fun most of the time, although occasionally one reveals his or her wariness.

It is difficult to know what the children sent to Mont Alto thought about the preventorium, as poor children leave few written records of their thoughts. Those few youngsters who did write or speak about their experiences later on recalled profound homesickness and confusion as to why they had been sent away. There was no standard length of stay. Some children remained for a short time, such as a summer, while others did not go home for months or years. Each place had its own rules. Like other children’s institutions of the era, life at the preventorium was highly regimented, with strict times to wake up, eat, play, rest, and attend school out-of-doors to maximize exposure to fresh air with, as the film shows, an emphasis on American values. Children salute the flag. Snowball fights represented part of the prescribed treatment regimen, not just the opportunity to have fun. The treatment goal was to gain weight and learn healthy habits. In an effort to maximize the influences of nurses and other staff on children, families were discouraged or actively prevented from visiting, even if the parents did not have TB.

TB Nurses

In almost every scene in which children play, rest, eat, or drink in this video, the viewer sees a “tuberculosis” nurse. They are easy to identify because of their starched white uniforms and caps. Sometimes she (and it’s always a she; women comprised almost all nurses in this era) is in the foreground talking to a child, taking his or her temperature, or performing a treatment. But there are also scenes in which the nurses are relaxing and having fun, even swinging as a group on the playground. Walter Zeigler, in his narration, recalls that nurses often married other employees and settled nearby, living out their lives in the area. Who were these women? How did one become a tuberculosis nurse?

Antibiotics Arrive

The therapeutic aim of building resistance to TB through the preventorium’s strict regimen of fresh air, ample nutrition, and education regarding health, morality, and good citizenship began to fade in the 1930s as improved public health measures began to stamp out TB. The notion of sending children away from their families declined in popularity as the TB-infected child no longer represented the norm. Rather, the cases that were identified were seen as a public health failure. The introduction of streptomycin in 1944, followed by isoniazid in 1952, meant that TB became a disease treatable with outpatient therapy. Institutions such as Mont Alto closed or were converted for other uses.

Tuberculosis preventoriums in the early 20th century were part of a broader scheme under the guise of disease prevention, with powerful entities like the Rockefeller Foundation playing a significant role. These institutions claimed to house at-risk children, particularly from poor and immigrant families, to protect them from TB. However, this so-called pandemic served as a tool for social engineering and control, separating children from their families and indoctrinating them with "American values" under the pretense of health care.

The Rockefeller Foundation, known for its influence over public health policies, provided substantial funding, including a $10,000 donation in 1912, to expand this system. The Rockefeller Foundation likely poured millions of dollars into tuberculosis preventoriums and sanatoriums globally over decades, leveraging their financial influence to shape public health policy and lobby for government funding to expand these programs, ensuring their control over the narrative and the institutions involved.

Far from altruistic, these efforts prioritized assimilation, control, and experimentation over genuine care for children, raising serious questions about what truly happened to those sent to preventoriums and the broader motives behind these programs.

Was Pirquet’s death in 1929 truly a suicide, or could it have been tied to something he witnessed, uncovered, or challenged? In the chaotic postwar landscape of Vienna, his innovative focus on nutrition and pediatrics may have clashed with the vaccine-centric strategies promoted by dominant global health organizations. Could his work have exposed uncomfortable truths or disrupted powerful agendas? The mystery surrounding his death invites deeper reflection on the potential conflicts between addressing fundamental human needs and advancing institutional priorities—a tension that continues to shape public health today.

It is truly puzzling that someone who made such significant contributions to public health and science has been almost entirely forgotten. Everyone I’ve asked about Pirquet has no idea who he is or has even heard of him. Was this intentional? Names like Pasteur are universally recognized, yet Pirquet’s legacy has seemingly been erased from history.

A Suspicious Death: Suicide or Silencing?

On February 28, 1929, Clemens von Pirquet and his wife were found dead in their Vienna apartment from potassium cyanide poisoning. The circumstances surrounding Clemens von Pirquet and his wife’s deaths are riddled with inconsistencies and suspicions. It is noted that in some of the publications of his death it was noted that there was no plausible reason for why Pirquet and his wife would have killed themselves. Some reports claim Pirquet was mentally ill and addicted to pain pills, while others suggest his family’s hostility toward his wife, Maria von Husen, drove her to mental instability and addiction to barbiturates. There are other rumors that she was terminally ill and this drove them to commit suicide together even though he was at the height of his career.

It just doesn’t add up! These allegations feel less like facts and more like part of a smear campaign to tarnish their reputations. Officially ruled a double suicide, their deaths were attributed to financial difficulties and a troubled marriage—but these explanations seem flimsy at best.

Adding to the mystery is the supposed stressful court case Pirquet had brought against his siblings, but little information is given in regard to why. Why was this legal battle happening, and could it have played a larger role in their tragic end? The unanswered questions leave a cloud of suspicion over the entire story. However, this explanation raises significant doubts:

Unlikely Circumstances: Von Pirquet was at the height of his career, holding one of the most prestigious positions in European medicine and actively engaged in public health work.

Enemies in Medicine and Elite Institutions: His critiques of antitoxin therapies and his refusal to align with powerful institutions like the Pasteur Institute likely created enemies in the medical-industrial complex. He also touted nutrition as being the main treatment for a host of illnesses including tuberculosis.

The Cyanide Mystery: Potassium cyanide, a substance often associated with deliberate poisoning, adds to the suspicion that his death may not have been self-inflicted.

In 1925, prior to his supposed suicide, Pirquet had encountered an "accident" in Karlsbad. It casts an eerie shadow over Pirquet's life and death, especially when viewed through the lens of his unexpected double suicide with his wife in 1929. The 1925 incident was described as a bizarre inadvertent misstep under the influence of painkillers, leading him to jump out of a hotel window while at a conference, breaking his leg and causing “other” injuries. However, in the aftermath of his death, the narrative took a sharp turn, with media retroactively framing it as a prior suicide attempt. But was it really? Or is this convenient reinterpretation masking something far more sinister?

The circumstances surrounding the 1925 event are suspicious at best. How exactly did Pirquet come to be in a state that led to such a dramatic act? The explanation of "painkillers" seems oddly vague—what kind of medication was he taking, and who administered it? Could he have been poisoned or drugged by someone with malicious intent? After all, jumping out of a hotel window is not a typical side effect of painkillers. Was he suffering from genuine disorientation, or was something more deliberate at play? There is no concrete evidence to rule out the possibility that someone pushed him or staged the fall, using his injuries as cover to make the incident seem accidental.

Equally troubling is the abrupt shift in the narrative after Pirquet's death in 1929. Initially reported as a tragic but accidental misstep, the Karlsbad incident was suddenly recast as a prior suicide attempt. This re-framing feels less like an attempt to understand the truth and more like an effort to craft a cohesive story around his later death, smoothing over inconsistencies and preemptively shutting down any uncomfortable questions. Why was this reinterpretation so readily accepted, and who benefited from steering public perception in this direction?

The political and professional context of Pirquet’s life adds further intrigue. The post-World War I era was a turbulent time, especially for prominent figures like Pirquet, whose groundbreaking work in immunology may have placed him at odds with powerful interests. Was his uncompromising nature—and potential refusal to align with prevailing political or scientific agendas—enough to make him a target? Could someone have seen him as a threat and sought to harm him, first in 1925 and, perhaps, again in 1929?

The Karlsbad incident remains an enigma, with its details cloaked in ambiguity and unanswered questions. Was Pirquet truly impaired by medication, or was he deliberately poisoned to render him vulnerable? Did he jump, or was he pushed? And why did the narrative surrounding this event conveniently shift after his death? These lingering uncertainties cast a long shadow, suggesting that the 1925 “accident” might not have been as accidental as it seemed—and that the truth about Clemens von Pirquet’s tragic end remains frustratingly out of reach.

Was von Pirquet silenced for exposing flaws in celebrated treatments and challenging the powerful institutions profiting from them? Or did the pressures of his career and personal life drive him to despair? The lack of comprehensive records only deepens the mystery surrounding his death.

Legacy: A Visionary Overshadowed by Controversy

Clemens von Pirquet’s contributions to medicine revolutionized immunology, public health, and pediatrics. His discoveries—allergy, serum sickness, and the tuberculin skin test—continue to impact medical practice today. His later work on nutrition and social determinants of health reflected a holistic approach that was ahead of its time.

However, his refusal to conform to the growing medical-industrial complex likely made him a target. His critiques of antitoxin therapies, which challenged powerful institutions like the Pasteur Institute, and his professional independence may have threatened entrenched interests. Given his brilliance and dedication to improving public health, it is highly unlikely that he would have willingly ended his life.

Clemens von Pirquet, A Pioneer Silenced?

Clemens von Pirquet was a revolutionary thinker who challenged the dominant medical narratives of his time. His discoveries reshaped modern medicine, but they also disrupted the powerful systems that profited from flawed treatments. The official narrative of his death as a suicide fails to account for the suspicious circumstances surrounding it and the pressures he likely faced. Was he silenced for exposing the flaws of early 20th-century medicine? Or did his independent stance make him a threat to the medical establishment? Von Pirquet’s story, marked by brilliance, integrity, and tragedy, serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of challenging power in the pursuit of truth.

What an interesting piece of history! It is like we are all looking at one of those pixel 3D pictures. And it keeps popping into 3D and back into 2D dots.

Keep them coming please! 🍿🍿🍿

Nice work. Thanks. Seems like one key is malnutrition. Heard once that this malady was unknown in parts of the East until sugar cane exports from Formosa became widespread, popularly consumed.