The War Production Board, Malaria Control, and the CDC

How DDT and "Elite" Networks Contributed to a False Public Health Narrative

The story of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), formerly the Communicable Disease Center (CDC), is often presented as a narrative of dedicated public health officials working to combat disease. However, a deeper dive into its origins reveals a complex web of corporate interests, financial elites, and influential figures that shaped both wartime and post-war public health policies. At the heart of this story are the War Production Board (WPB), the widespread use of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), and key players like Sidney Weinberg and John J. McCloy, whose connections to the World Bank and powerful banking families played a crucial role in shaping these policies.

The Formation of the War Production Board

Freemason President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the War Production Board (WPB) on January 16, 1942, through Executive Order 9024.

The creation of the WPB aimed to coordinate the production of war materials and manage the allocation of resources critical to the U.S. war effort.

Roosevelt’s decision to form the WPB was purportedly driven by the need to streamline industrial production and ensure that the U.S. military and allies received the necessary supplies to combat Axis forces. WPB, established during World War II, was responsible for converting civilian industries to war production, allocating scarce materials, and controlling nonessential production. It supervised the production of $183 billion (equivalent to $2.46 trillion in 2023) worth of weapons and supplies, accounting for about 40% of global munitions output.

The national debt increased dramatically as a result of this borrowing, growing fivefold to $259 billion by 1945, which is roughly $4.6 trillion in today's dollars. The Revenue Act of 1942 was instrumental in this financial strategy, expanding the income tax base from 13 million to 50 million Americans and imposing higher taxes on excess profits, thereby shifting a greater share of the financial burden onto taxpayers.

This period of increased taxation and borrowing marked a significant instance of wealth redistribution in modern history.

Under the leadership of Donald Nelson and later Julius Albert Krug, the WPB prioritized materials like steel and rubber for military use, restricted consumer goods, and mobilized public support through patriotic campaigns.

The board's efforts led to a dramatic increase in military production, such as a rise in aircraft manufacturing from 6,000 in 1940 to 85,000 in 1943. The WPB was dissolved in November 1945, transitioning its responsibilities to the Civilian Production Administration.

Donald M. Nelson, a businessman with ties to the American business elite, led the WPB. Nelson’s leadership was characterized by efforts to mobilize industry for war production, but the board’s operations were heavily influenced by financial and industrial interests. The WPB’s advisory committees included influential figures from various industries, including those with connections to the Rockefeller and Morgan networks.

Donald M. Nelson, born in Hannibal, Missouri, graduated from the University of Missouri in 1911 with a degree in chemical engineering. He joined Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1912 as a chemist and steadily advanced, becoming vice president by 1930 and executive vice president by 1939. Nelson’s extensive experience at Sears, where he oversaw the purchasing of over 135,000 products, equipped him with deep knowledge of American industry. This expertise led President Franklin Roosevelt to appoint Nelson to oversee war material production for the U.S. and its allies during World War II, starting with a role in the Treasury Department in 1940.

Julius Albert Krug, who served as Chairman of the War Production Board (WPB) from 1944 to 1945, played a pivotal role in managing the United States' industrial and resource mobilization during World War II. His work in overseeing wartime production laid foundational principles for post-war economic policies and international cooperation. After the war, Krug's expertise and influence extended into global affairs, notably contributing to the establishment of the United Nations and its agencies. His efforts helped shape the post-war economic and geopolitical landscape, reflecting a “seamless” transition from wartime industrial management to peacetime global governance.

John J. McCloy, who served as Assistant Secretary of War during World War II, was closely involved in wartime policies. McCloy’s influence extended into the post-war period as President of the World Bank, where he continued to shape global financial and public health policies. His connections to the Rockefeller and Morgan families further influenced the WPB’s policies.

William S. Knudsen, a prominent industrialist and former president of General Motors, served as the director of the WPB’s Production Division. Knudsen’s connections with major industrial players ensured that wartime production favored industries with ties to financiers. He was a Danish-American auto industry executive who played a major role in U.S. war production during World War II. Known for his time at Ford and General Motors, where he oversaw mass production, Knudsen was recruited by President Franklin Roosevelt not because of any altruistic motives, but due to his expertise in maximizing industrial output for profit. Commissioned as a lieutenant general in the U.S. Army, Knudsen became instrumental in the War Production Board's efforts to ramp up manufacturing of military equipment. His work contributed to the large-scale mobilization of resources, but his close ties to the corporate world raise questions about whether this was more about serving the interests of big business than purely patriotic duty.

Sidney Weinberg, a Jewish senior partner at Goldman Sachs nicknamed "Mr. Wall Street”, played a pivotal role in persuading Roosevelt to create the WPB. Known for his deep connections to influential banking families like the Rockefellers and Morgans, Weinberg was instrumental in shaping the WPB’s objectives and policies. His connections with the Rockefeller family, which had significant stakes in Standard Oil and other chemical industries, were crucial. Weinberg’s influence ensured that these industries were prioritized during the war.

In May 1941, Sidney Weinberg took a leave of absence from Goldman Sachs to join the Office of Production Management (OPM) in Washington, DC, which was tasked with preparing the U.S. for wartime mobilization. When the War Production Board (WPB) replaced the OPM in January 1942, Weinberg transitioned to the WPB as assistant to the Chief of the Bureau of Industry Advisory Committees and later to the Chairman. His main role was to secure top executive talent for the board, working for a nominal salary of $1 per year.

When the U.S. entered World War II in 1941, Sidney Weinberg played a crucial role in mobilizing America's private sector to address significant financial and industrial challenges. He firmly believed that "government service is the highest form of citizenship" and was committed to serving only in wartime. Recognizing his success in recruiting corporate talent for the Business Advisory and Planning Council, President Roosevelt tasked him with forming the Industry Advisory Committee under the War Production Board. Weinberg personally visited CEOs, urging them to provide their best young executives for the war effort.

His efforts not only secured “top talent” but also strengthened his connections with leading businessmen. After the war, these relationships enhanced Goldman Sachs' prestige, as many executives who had worked with Weinberg hired him as their investment banker and invited him to join their boards. Weinberg served on the boards of several major companies, including Ford Motor Company, General Electric, Sears Roebuck, Continental Can, National Dairy Products Corporation, B.F. Goodrich Company, and General Foods Corporation. Notably, his support for Henry Ford II during Ford Motor Company's transition to peacetime production led to Goldman Sachs managing the largest IPO in U.S. history at that time, raising nearly $700 million. Interestingly, many of these companies, like the Ford Motor Company, funded Nazi Germany as well during WW2.

Weinberg applied his business expertise to ensure efficient war production and coordinated a network of private sector talent to fill government positions. After returning to Goldman Sachs in August 1943, he rejoined the WPB as vice chairman of Special Programs from June to September 1944. Weinberg’s dedication to public service was recognized with the Medal for Merit in 1946. During World War I, Weinberg enlisted in the Navy, serving as a cook due to his poor eyesight. He would rise to finish his service as Assistant Special Agent of the Navy Intelligence Department and the War Trade Board, and Deputy Collector of Customs at Norfolk, Virginia with the rank of Chief Boatswain’s Mate., stating he would only accept such roles in times of conflict.

Weinberg’s role extended beyond mere persuasion; he actively helped shape the WPB’s policies to favor industries aligned with Wall Street interests. His connections to financial elites ensured that the WPB’s initiatives supported the production of chemicals, including DDT, which would later become central to public health campaigns.

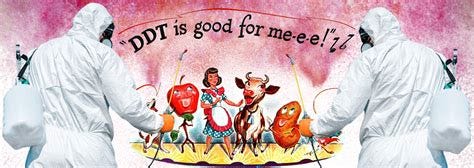

One of the WPB’s significant achievements was its role in promoting the production of DDT, a chemical initially developed for pest control. The chemical, produced by companies linked to the Rockefellers, was introduced as a solution for controlling mosquito-borne diseases. The WPB’s policies favored the chemical industry, ensuring that DDT and other chemicals were prioritized in wartime production.

During WWII, pesticide companies capitalized on the military's insect elimination campaigns. FLIT, a Standard Oil brand, ran ads linking their products to the war effort, even enlisting Dr. Seuss to create wartime imagery of soldiers fighting bugs. These campaigns, along with the promotion of DDT and arsenic-based insecticides like Paris Green and lead arsenate, convinced Americans that pesticides were crucial for victory. Domestic sales of these chemicals surged to record levels, and by 1944, arsenic supplies were depleted, pushing Americans to seek alternative pest control methods.

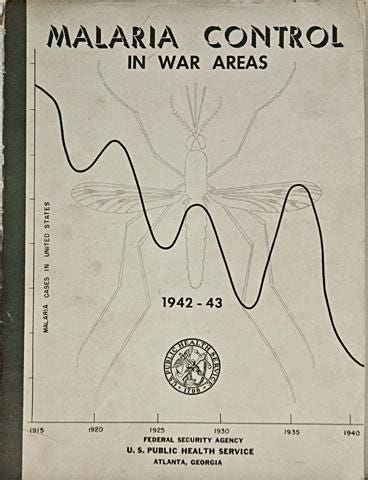

As the War Production Board promoted its production, DDT output neared its peak wartime level of three million pounds per month by May 1943, when it was added to the Army's supply lists, and by January 1944, to the Navy's supply lists. During this period, almost all DDT was allocated to the armed services, with only a few hundred thousand pounds reserved for additional experimentation.

The Rockefeller Foundation played a crucial role in the development and promotion of DDT through its International Health Division (IHD), which provided essential funding and support for early research into insecticides. In the 1940s, the Foundation's backing was instrumental in advancing the research and commercialization of DDT, a chemical touted for its potential to revolutionize "malaria" control.

This support facilitated collaborations with major chemical companies such as Merck & Co., Monsanto, Ciba-Geigy (now part of Sandoz), and Geigy, which were directly involved in the production and distribution of DDT. The Rockefeller Foundation not only funded research but also actively promoted DDT through public health campaigns, presenting it as a "miracle" solution for controlling "malaria" and other supposed vector-borne diseases during and after World War II.

DDT isn't made directly from coal, but its production involves chemicals that can be linked to coal or petroleum (which is right up Rockefeller’s alley). DDT is created through a chemical process involving chloral and dichlorobenzene. While chloral is made from ethanol, which may use petrochemical processes, dichlorobenzene can come from coal tar, a byproduct of coal. So, while coal isn't a direct ingredient in DDT, the chemical industry’s use of coal and oil products in producing the raw materials for DDT connects the chemical to these energy sources.

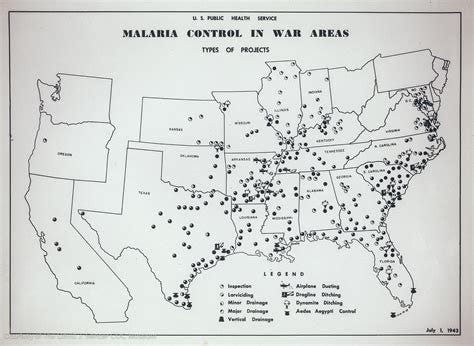

The Rockefeller Foundation’s influence extended to the establishment of the Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA) program (the predecessor to the Communicable Disease Center which later became the Centers for Disease Control or CDC), which heavily relied on DDT for its operations. The supposed lack of space in Washington due to the war effort allowed the program to base its headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, and closer to the work at hand. But it is suspect what this work really was.

Before the MCWA program and CDC organization's founding, global “malaria” control efforts were led by influential groups like the Malaria Commission of the League of Nations (now known as the United Nations) and the Rockefeller Foundation. The Malaria Commission was established in 1923 by the League of Nations to coordinate international efforts against malaria. The Rockefeller Foundation played a major role in supporting malaria control, pushing for government involvement in its initiatives and working in partnership with the agency.

This program, along with other post-war public health initiatives, emphasizes the Foundation's role in integrating DDT into global "malaria" control efforts. Initially, DDT supposedly contributed to significant reductions in "malaria" incidence, showcasing its supposed effectiveness (or maybe just manipulation of statistics much like we see today). However, the long-term environmental and health impacts of DDT, including its persistence in ecosystems and associated health risks, eventually sparked controversy. This led to the chemical’s supposed ban in many countries as its detrimental effects became increasingly apparent. But it is still produced and used today. It has also been disposed of throughout the oceans and in undisclosed areas. The total impact is highly publicly understudied and unknown.

The Rockefeller Foundation’s involvement highlights how philanthropic organizations can shape public health policies and industrial practices, often aligning with the interests of chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

By promoting DDT and integrating it into major public health campaigns, the Foundation influenced the direction of "malaria" control strategies while also affecting broader health narratives. The legacy of DDT's use, coupled with the eventual backlash over its environmental and health impacts, illustrates the complex interplay between philanthropy, industry, and public health policy, revealing how major players can drive both the creation and resolution of health crises.

The Impact of Silent Spring and the DDT Controversy

Silent Spring, published by Rachel Carson in 1962, was a pivotal work that brought to light the environmental and health risks associated with DDT, a widely used pesticide. Carson's book detailed how DDT, while effective against pests and disease vectors like mosquitoes, had devastating effects on wildlife and ecosystems. She documented how DDT accumulated in the food chain, leading to the decline of bird populations and potentially harming human health. Her work sparked significant public and scientific debate, leading to greater scrutiny of pesticide use and the eventual ban of DDT in the United States in 1972. Carson's revelations underscored the need for pest control methods that would not endanger human health or disrupt natural ecosystems.

Persistent Use and Environmental Impact of DDT

In the United States, DDT has been banned for nearly all uses since 1972 due to its harmful environmental and health impacts, such as causing eggshell thinning in birds like eagles and falcons. Mysteriously, avian species like bald eagles are still dying en mass and scientists can’t figure out why. (Pfffft!) Total mystery! But they explain it away with supposed Germ Theory based explanations, but of course it just couldn’t be DDT that stays in the environment for over 100 years (if not longer).

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) prohibits its use for agricultural purposes, pest control, and most other applications. However, exceptions allow DDT to be manufactured in the U.S. for export to certain developing countries, where it is used to control “disease vectors” like mosquitoes allegedly responsible for "malaria." This continued use often targets poor regions rich in natural resources, raising suspicions about the true motives behind its application. Fortunately, organizations such as the World Bank and the Merck based out of the United States are committed to overseeing “health” programs in these regions, ensuring public health through extensive pesticide applications and the promotion of synthetic pharmaceuticals.

But try not to dwell too much on the fact that they've been spraying pesticides into these regions' water sources for decades. Surely it’s not causing harm to the people, just as it supposedly didn’t affect the bald eagles.

Despite the supposed ban, DDT was still utilized within the U.S. after 1972. For instance, in January 1979, it was used to control fleas carrying typhus in Louisiana, and that same year, California used it against fleas spreading supposed bubonic plague. Texas received exemptions for DDT use to combat rabid bats in October 1979. Between 1972 and 1979, DDT was also used for pest control on crops and against various health threats in multiple states.

DDT’s persistence in the environment is troubling; it can remain for decades due to its chemical stability, leading to widespread contamination. Military forces have disposed of DDT in oceans and other unknown locations, exacerbating its environmental footprint. Given the historical record of government and military involvement in secret experiments and controversial practices, there is justified skepticism about whether the U.S. truly ceased all domestic use of DDT. The compound’s long-term accumulation in the food chain and its impact on human and wildlife health emphasizes the complexity and potential risks associated with its ongoing production and export.

DDT, despite supposedly being banned in many countries decades ago, still persists in the environment and has even been found in remote regions most remote parts of the world, including Antarctic snow and in penguins there. This highlights the pesticide’s ability to travel vast distances through atmospheric circulation. In Antarctica, DDT has been detected in the fat tissue of penguins, demonstrating that the chemical has entered the food chain in these untouched ecosystems. DDT is also still being found in aquatic life across the globe, with fish and other marine species showing traces of this persistent pollutant.

In human fat cells, DDT and its breakdown products like DDE continue to be detected at alarming levels. A study found that over 90% of people tested in the U.S. had DDT or its derivatives in their fat tissues. Some individuals showed concentrations well above the allowable amounts, with levels often exceeding the recommended 1 mg/kg safety threshold. This ongoing accumulation poses serious health risks, given DDT's known links to cancer, reproductive issues, and other chronic illnesses.

Despite its ban, DDT’s toxic legacy endures, persisting in both humans and the environment.

The CDC, Coca-Cola, and DDT: Unveiling Hidden Agendas and Elite Connections

In 1946, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was established as the Communicable Disease Center. While publicly touted as a critical development for combating "malaria" in the southern United States, its origins and activities reveal a troubling narrative of elite manipulation, public health deception, and hidden agendas.

The League of Nations and Its “Malaria” Commission: Elite Control Under the Guise of Public Health

Before the CDC's founding, the League of Nations “Malaria” Commission, influenced by elite banking families and global financiers, played a prominent role in “malaria” control efforts. The League, established to foster international cooperation and prevent conflicts, became a tool for extending elite control under the guise of public health. The Rockefeller Foundation’s involvement in “malaria” control, while ostensibly philanthropic, was driven by strategic interests. The Foundation sought to shift responsibilities to national governments and expand its influence.

Transition to the Communicable Disease Center

The Communicable Disease Center was established on July 1, 1946, succeeding the World War II Malaria Control in War Areas program of the Office of National Defense Malaria Control Activities. This transition marked a shift from international to national control, focusing on the southern United States due to its reported prevalence of "malaria." The decision to base the CDC in Atlanta, Georgia, was influenced by Coca-Cola’s support and the region’s significance for pesticide application.

Coca-Cola’s Dubious Role: Corporate Influence and Nazi Ties

Robert W. Woodruff, then-president of Coca-Cola, played a crucial role in establishing the CDC in Atlanta. Woodruff’s support was publicly presented as philanthropic but was marred by Coca-Cola’s Nazi affiliations during World War II. The company’s German subsidiary operated under Nazi control, raising questions about its loyalties and the nature of its support for the CDC. Woodruff’s backing seems to have been driven by corporate and strategic interests, leveraging influence rather than genuine health concerns.

The Heavy Use of DDT: Health Impacts and Controversies

During the post-war era, the Malaria Control in War Areas program extensively used DDT in the southern United States. This aggressive application of the pesticide, aimed at controlling "malaria," led to severe health consequences:

Health Impacts: The extensive use of DDT resulted in numerous health issues among Southern residents, including headaches, dizziness, respiratory problems, and other symptoms linked to the pesticide's toxic properties. Long-term exposure has been associated with increased rates of cancer and other serious health problems.

Interesting…

Lawsuits and Legal Actions: The health effects of DDT led to lawsuits in states like Alabama, where residents sought legal redress for health problems caused by pesticide exposure and in California where tons of this dangerous chemical have been disposed of. These legal cases reflect the severe impact of DDT on the health of individuals in the region.

Cancer Statistics: The southern United States has significantly higher cancer rates compared to other regions in the U.S. This elevated cancer incidence is believed to be linked to the historical use of DDT and other pesticides. The region’s higher cancer rates underscore the long-term health consequences of such public health policies.

Malaria Control in War Areas: Pesticide Spraying in the U.S.

The Malaria Control in War Areas program, initiated during World War II, involved extensive spraying of DDT in the southern United States. This program aimed to control "malaria" by eliminating mosquitoes, but it had several significant implications:

Scope of Spraying: The program covered large areas in the South, including residential neighborhoods, agricultural lands, and military installations. The extensive use of DDT was intended to control mosquito populations and reduce the incidence of "malaria."

Health Effects: The indiscriminate application of DDT led to widespread exposure among the population. Residents reported adverse health effects, such as respiratory issues, skin irritations, and neurological symptoms, which were later linked to the toxic properties of DDT.

Environmental Impact: The heavy use of DDT also had significant environmental consequences. The pesticide accumulated in the food chain, affecting wildlife and leading to the decline of certain bird species. The environmental damage from DDT use contributed to long-term ecological consequences.

Scandals and Controversies within the CDC

The CDC’s early leadership was tainted by scandals, including the involvement of Dr. Thomas Parran Jr. in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (which can also be linked back to the Salk Institute and World Bank). This unethical study, which deliberately withheld treatment from African American men to observe the progression of what was supposedly syphilis, reflects serious moral and ethical failings within the CDC’s history. But who knows what they really did to these poor people????

Why the Elite Targeted the South: Strategic and Resource-Based Motives

The intense focus on the southern United States for malaria control reveals several potential motives behind the elite's interest in the region:

Economic Control: The South’s significant agricultural output, including cotton and tobacco, made it economically valuable. Controlling pests through aggressive pesticide use helped stabilize and profit from these industries.

Natural Resource Exploitation: The South is rich in natural resources, such as minerals, oil, and timber. Elite interests likely sought to secure and exploit these resources through control of the region.

Political and Financial Power: The South’s resistance to federal intervention and central banking might have made it a target for consolidation of political and financial control, allowing the elite to undermine regional autonomy.

Social and Economic Influence: The South’s distinct social and economic structures provided an opportunity for the elite to extend their influence and control. By shaping public health policy, they could alter social dynamics and reinforce their power structures.

Unmasking the True Agenda

The League of Nations Malaria Control Committee and subsequent CDC creation, influenced by Coca-Cola’s controversial support and the extensive use of DDT in the South, reveals a complex narrative of power and control. The public health policies implemented under the guise of combating "malaria" were deeply entwined with elite agendas for economic control, resource exploitation, and political influence.

The severe health impacts of DDT, including adverse effects, legal actions, and elevated cancer rates in the South, highlight the harmful consequences of these public health policies. The scandalous history of CDC figures further sheds light on the ethical issues associated with these organizations and corporations and their initiatives.

This historical context challenges us to critically assess the true motives behind public health efforts past and present. What was presented as a benevolent initiative to combat "malaria" was, in reality, a tool for elite manipulation and control which is still felt today. The legacy of these actions serves as a stark reminder of how public health can be used as a facade for more insidious agendas, affecting countless lives in the process.

The whole DDT thing... I was vaccinated against DDT...er..."polio" in 1963, and gained a lifelong affliction of psoriatic arthritis. I did a video about it:

Why I Am This Unspeakable Thing (5 min): https://odysee.com/@amaterasusolar:8/why-i-am-this-unspeakable-thing-5:8

It is so ghastly what these psychopaths in control are doing to Humanity, and if We do nothing - PERSONALLY - They will win. If enough of Us stand in aggregate against Them, We will win. I am doing My part:

The GentleOne’s Solution (article): https://amaterasusolar.substack.com/p/the-gentleones-solution

Excellent article.